Table of Contents

The history of science and technology is one of constant experimentation, improvement, innovation and failure by countless individuals and entire industrial sectors. However, through their discoveries, some individuals were able to open up huge prospects linked with the use and spread of specific technologies.

And the world of printing is no exception. This is why today we’ll be talking about five men who changed the world of printing forever: from Germany where it all began, to Italy, home of many innovations that made printing cheaper, via France and the United States.

Johannes Gutenberg

We had to start with him: Johannes Gensfleisch, better known as Gutenberg. Born in 1400 in Mainz, the German city at the confluence of the Rhine and Main rivers, Gutenberg returned to his birthplace in the middle of the century to set up Europe’s first printworks.

A goldsmith by trade, Gutenberg is considered the father of printing. As well as introducing movable-type printing to Europe, Gutenberg was also responsible for three innovations that ensured the technology was a success:

- He produced movable type quickly and in large quantities using matrices made with a punch

- He was the first to use more durable oil-based inks instead of water-based inks

- He built the first printing press out of wood, inspired by the wine press

In Mainz, he printed 180 copies of Europe’s first book: the Gutenberg Bible. Today, just 49 of these remain, two of which are preserved in Mainz’s Gutenberg Museum.

Despite having invented one of the world’s most important technologies and being considered today one of the world’s most influential figures, Gutenberg had lots of financial troubles during his life, often finding himself penniless. Just three years before his death, his achievements were finally recognised and archbishop Adolph von Nassau made him a gentleman of the court, an honour which came with a stipend for clothes and food.

Aldus Manutius

Gutenberg might have invented printing, but books would look very different today without the innovations of Venetian Aldus Manutius. He invented the octavo, a book format printed at the end of the 15th and beginning of the 16th century in his printworks in Venice.

Octavos were considered the first portable and affordable books. To produce these books, Manutius pioneered the use of octavo printing: this involves printing on a large sheet which is then folded several times to create eight smaller sheets. The result was what is known as a “gathering” or “signature”, which was then bound together to make a book. Although the format can vary, this is essentially the way in which books are still printed today.

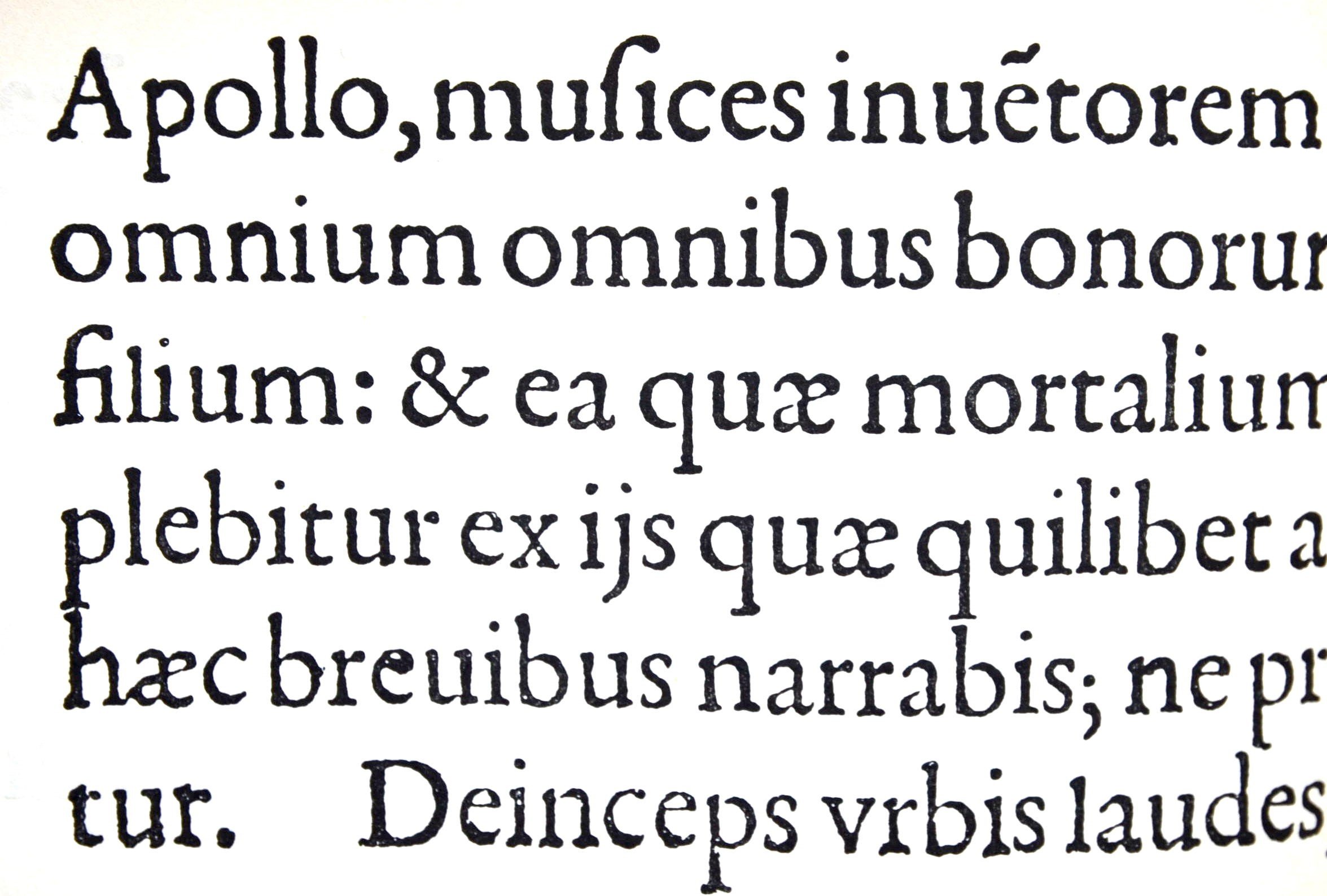

Aldus Manutius devised this technique with a very specific goal in mind: to save paper, thereby making books cheaper and more widespread (remember that the first Gutenberg book cost around 30 florins, or three years’ wages for a simple clerk). With the same goal in mind, Manutius invented the italic typeface, which allowed more text to be printed on a page compared to Gothic fonts.

Claude Garamond

Having visited 16th-century Germany and Italy, it’s time to move on to France, where we find Claude Garamond. Although he would spend much of his life dissatisfied with his earnings, today Claude Garamond is considered to have been one of the most influential figures in the history of printing.

Having visited 16th-century Germany and Italy, it’s time to move on to France, where we find Claude Garamond. Although he would spend much of his life dissatisfied with his earnings, today Claude Garamond is considered to have been one of the most influential figures in the history of printing.

He was one of the first to specialise in creating movable type as a specific service for printing, his typefaces becoming highly sought-after by the best printers in France. In 1531 he made his first “Roman” typeface, which would replace the Gothic fonts used hitherto in France.

If you’re still unconvinced of Claude Garamond’s importance, remember that the font that carries his name – Garamond, inspired by the typefaces he created – is one of the most widely used in the world today.

Giambattista Bodoni

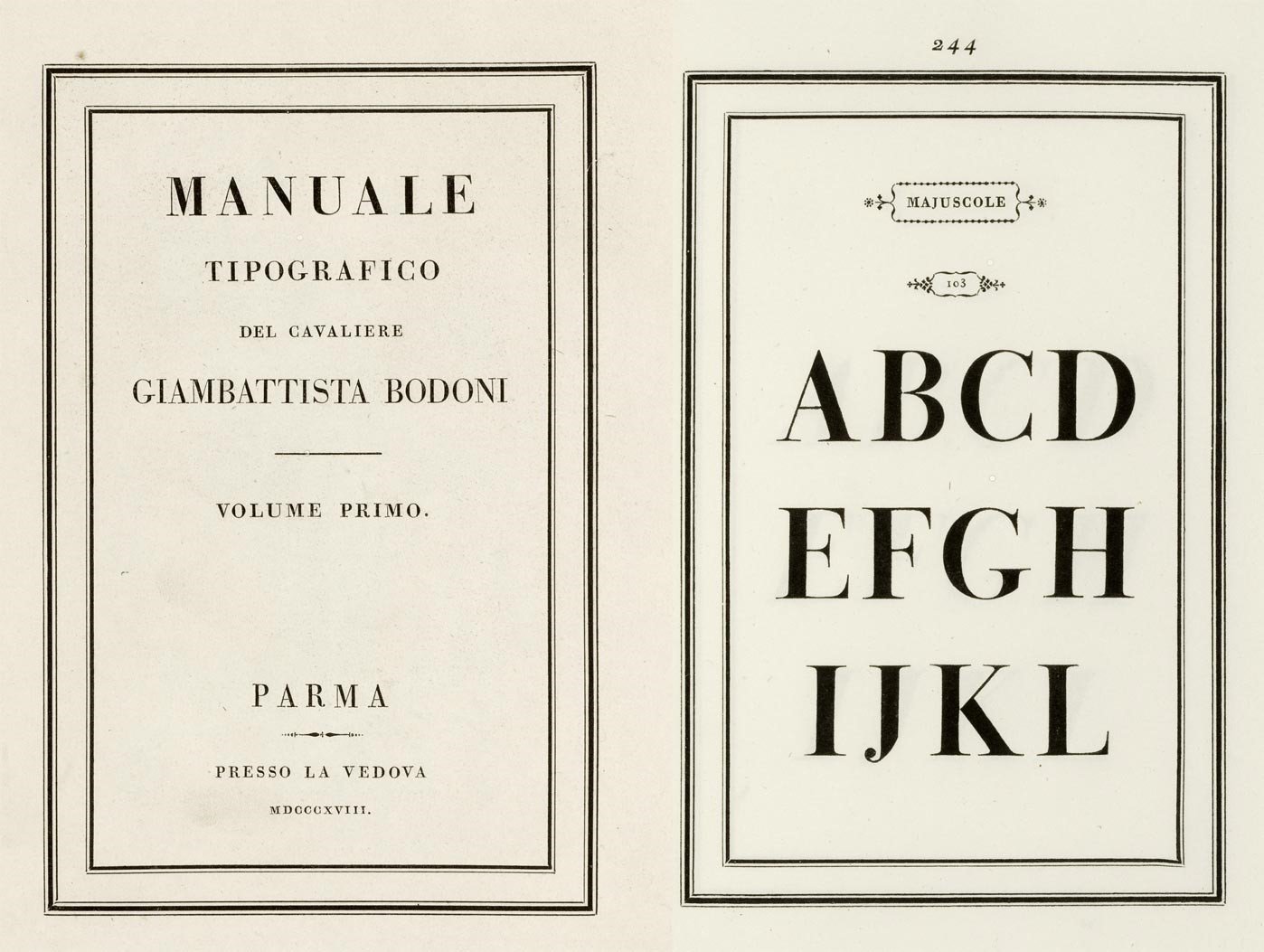

Giambattista Bodoni’s “Manuale Tipografico” [image: in the public domain]

We now return to Italy and the court of Parma. It was here between the 18th and 19th century that Giambattista Bodoni, the Italian printer and type designer, created the eponymous Bodoni font.

Bodoni undoubtedly changed the history of typography and would influence it for years to come. Created around 1798, this font is considered the first modern typeface due to two notable features: its fineness and simplicity. Taking the Baskerville font as a starting point, Giambattista Bodoni created a typeface with a clear contrast between the strokes (some thin, others thicker). In a further innovation, serifs were perpendicular rather than curved as they were in Renaissance fonts.

In his Manuale Tipografico, published in 1818, Bodoni also listed the four characteristics of a good font: uniformity, elegance, good taste and charm.

Gary Starkweather

As you well know, nowadays you can print documents in every home thanks to printers connected to PCs. We take this for granted, but it was a revolution. The advent of laser printers in the eighties kicked it off, but its origins can be traced to more than a decade earlier and to one man: Gary Starkweather a researcher at Xerox.

Gary Starkweather is a physicist and at Xerox he started experimenting with laser technology for photocopiers. Then he had an idea: why not use a laser to print a matrix generated by a computer?

It was 1971 when Starkweather began working on this idea. The result was the Xerox 9700, the first commercial laser printer, launched in 1977. The first office laser printer followed in 1981. But it was the hugely successful 8ppm Hewlett Packard LaserJet that brought the device to many homes for the first time.

Starkweather later left Xerox and went on to work for Apple and Microsoft. He took his well-earned retirement in 2005.