Table of Contents

If you read our article on the best calligraphy workshops in Paris, the name Julien Chazal will already be familiar to you.He’s a celebrated calligrapher artist who’s worked with some of the world’s most prestigious brands.Recently, he’s been expanding his horizons with artistic calligraphy projects while also campai

gning against illiteracy.We sat down for a chat with this renowned artist and chair of the calligraphy section of the Meilleurs Ouvriers de France competition, a prestigious award for the finest craftsmen in their field.

How did you discover calligraphy? And when did you decide to make a career of it?

I studied at the School of Art and Design in Nancy, France.There, abstract art dominated but I personally found that it lacked technique. It was while doing a course on the basics of page layout that I met an energetic teacher and great calligrapher who introduced me to this extremely wide-ranging world: pictorial and artistic diversity, the exploration of pigments etc. Unlike what I was studying at art school, calligraphy was precise and I liked that. It’s an art that rewards hard work, just like the work of artisans. The path from passion to career was not easy.

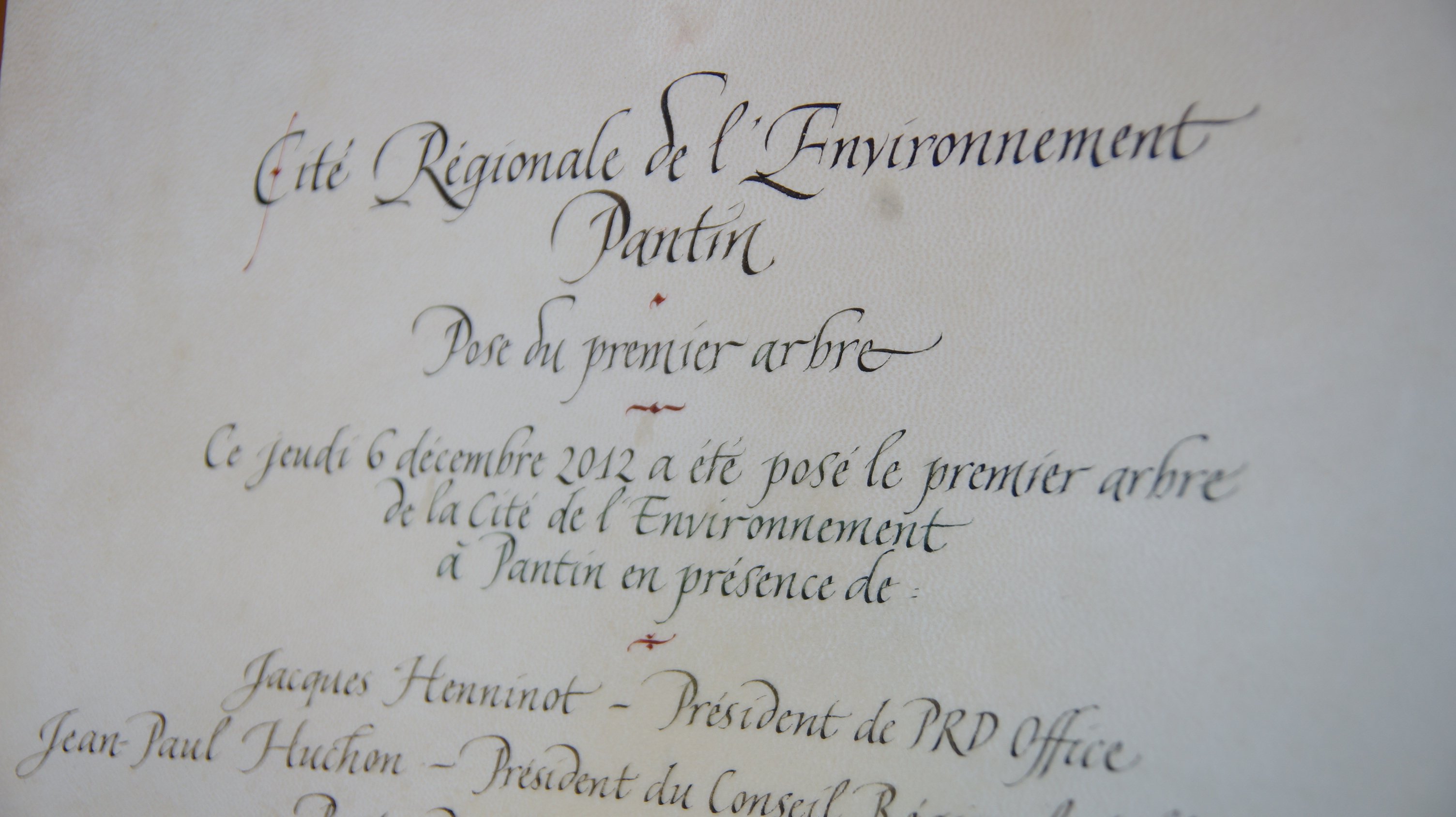

I moved to Paris and soon started giving lessons. Then I worked for communications agencies, publishing houses and the media. By meeting people and working, I got to be involved in interesting projects and so I got to live my passion. The luxury sector is quality-focused and therefore interested in calligraphy, so I went to the Paris fashion weeks, for example, to develop leads. Latin calligraphy has only very recently been recognised, so you have to make companies want to use it.

What do you write outside of work, just for your own pleasure?

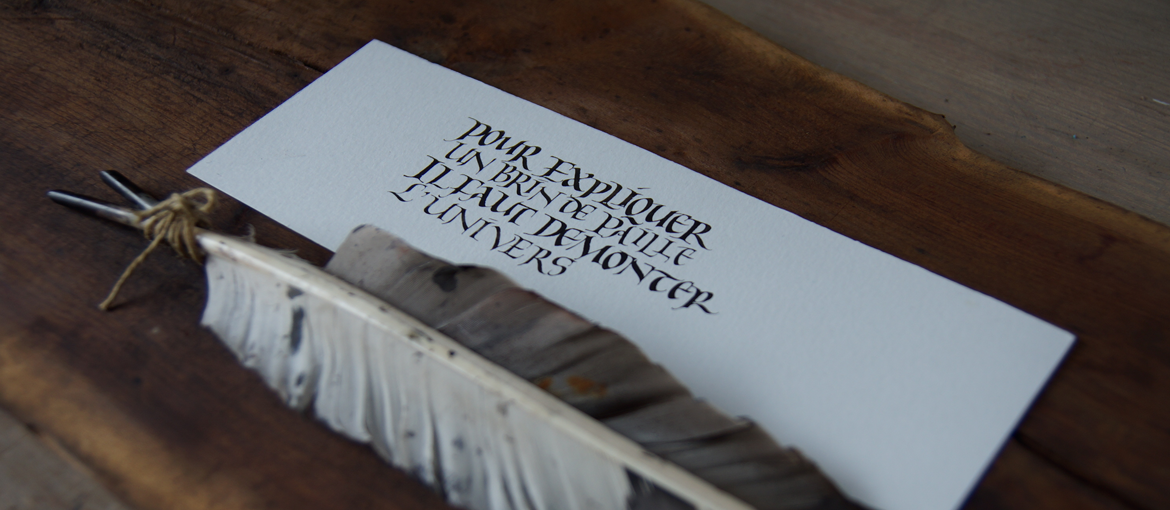

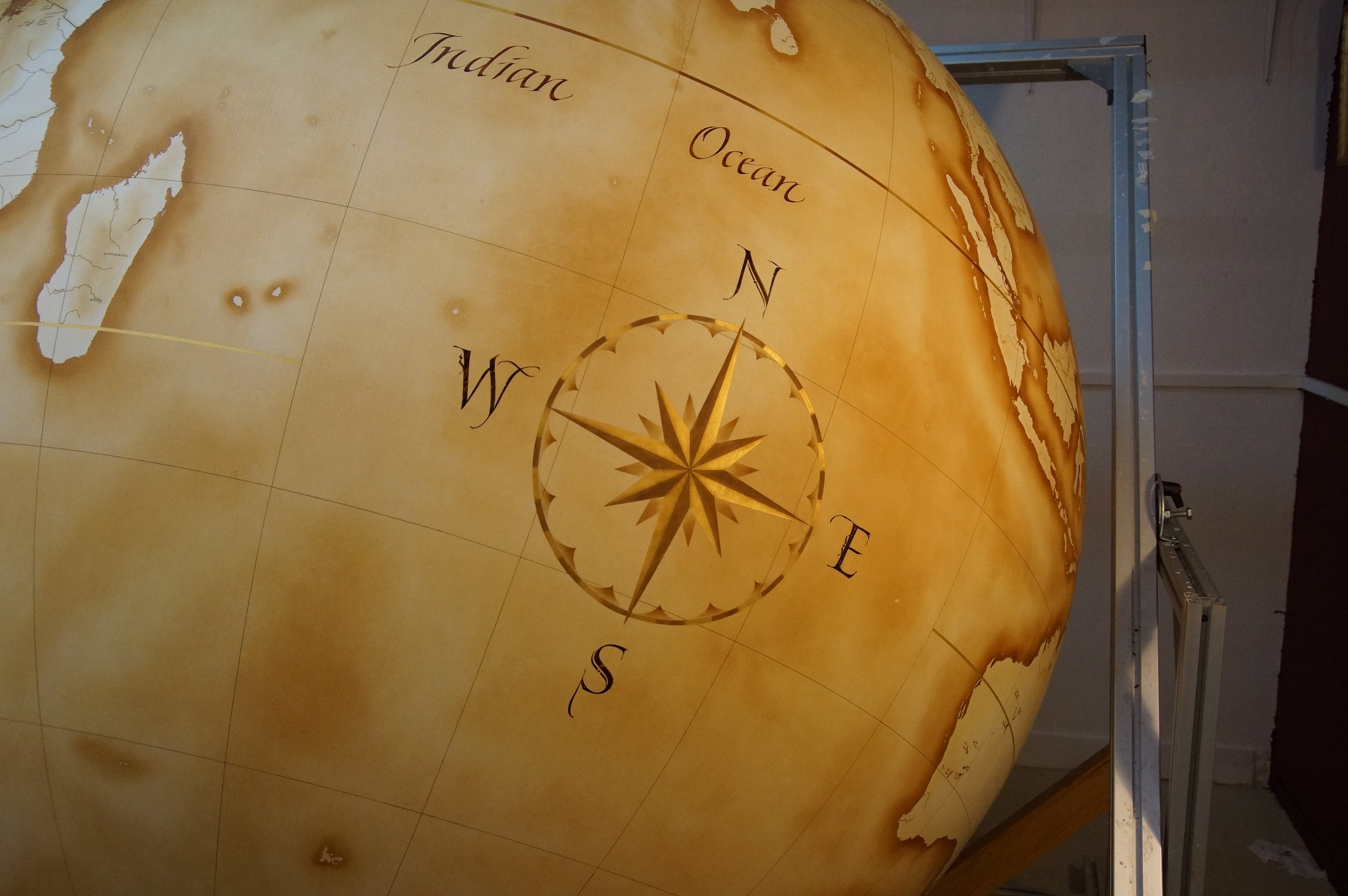

Before, I had lots of different projects. But now I make sure that I pick and choose them so that I do things that I value. I also do trials for creations with commercial potential: postcards, stone engraving, herbariums with calligraphy, mouldings… I have fun. These days, I also tend to head in a more artistic direction. I explore large formats in particular. Calligraphy has a dimension that is intrinsically connected with the body, which is interesting. Otherwise, simply for my own pleasure, I explore new materials, like parchment, glass and stone.

I try out new media, new pigments, new glues… I’m returning to portraits with a blend of drawing and calligraphy and my creations can range from street art to more intimate things. I particularly like to engrave natural materials, stone, wood, etc. There are still lots of things that I don’t have time to do!

Have you tried every type of calligraphy? You specialise in Latin calligraphy. Why?

There are three types of calligraphy: Asian, Latin and Arabic. I’ve tried them all but Latin calligraphy is part of my culture so I’m naturally drawn towards it. It’s a relatively unknown type, one that most people only really grasp when they are looking at medieval illuminations. The letters are everywhere but we don’t really see them, yet they are part of graphic culture: from medieval works covered in inscriptions to the paintings of Picasso, Klimt or Mucha. Calligraphy is recognised in its own right in Asia, but in Europe we distinguish between form and content.

Pieces of work must be of genuine interest, must be intellectualised, they can’t be simply aesthetically pleasing or “fun”, which I find a shame. Even when working on my commissions, whether for a sandwich or a perfume, I have to justify my approach.

Do you have any favourite tools?What type of brushes and pens do you prefer to work with?And what about paper?

I have a well-stocked studio, and that’s something I like about calligraphy: inkwells, pen holders and the like. All this is antithetical to technology but paradoxically it fits right in. Calligraphy is a way of life. Anything that leaves a mark on a medium can be used for calligraphy, it’s actually very simple. In every country, stone is engraved or paper is attacked with the pen’s metal, except in Asia, where absorption techniques are preferred. Asians caress paper, Europeans are more violent.

As for my favourite tools, it depends on the moment and on what I want to express. Flat and pointed brushes interest me a lot because they imply a different sensibility compared to metal. Otherwise, I use lots of standard typing paper, sometimes coloured paper, gravure paper or cotton paper, which is a bit luxurious. It all depends on the expression and result that I’m after.

Which word do you prefer writing? And which is your least favourite?

To tell the truth, I’ve been doing calligraphy for a very long time and I’m a bit tired of writing. But I can give you two words I like more than others. ‘Pangram’ first of all. It means sentences that are as short as possible but contain all the letters of the alphabet. They allow beginners to write all the letters of the alphabet while having a bit of fun doing so. I also like ‘petrichor’, the smell of stone after rain. Otherwise, I like to engrave the words ‘fuck up’, it’s not particularly politically correct but it lets me vent. What I don’t like are messages that are silly and predictable.

How do you see your work in the digital age? As a source of opportunity and new exploration or a limitation?

It’s a growing issue: the gap between hand writing and creating calligraphy fonts with a computer. Today, society is offering us something that is not good. A great calligrapher once said: “to calligraph is to resist mediocrity”. We’re living in an increasingly technological environment – everyone has a computer – but that’s not why people make great things. I work a lot with artisans in the 11th arrondissement of Paris, which is a crafts area. In the past, they used to build lots of different furniture there.

Today, in the age of IKEA, only the artisans catering for the luxury sector are still working. The same thing is happening with calligraphy. Being fluent in digital tools is a modern necessity, but in art that shouldn’t be the only thing that we learn to do. I’m involved in a project for fighting illiteracy in Guyana, and there is frustration in schools because the teachers themselves don’t know how to write, so the classrooms have computers. It’s a consumerist, easy way out that means that a key aspect of language is lost. Yet, I’ve seen that in just five lessons it’s possible to change someone’s handwriting. An effort needs to be made, which is essential for education.

Does calligraphy help us think about words in a better way? Do you see a therapeutic aspect to it?

This idea of therapy is very important when it comes to illiteracy. Calligraphy is about personalisation and reconstruction. Telling a student that they have been incorrectly taught handwriting, that it’s not their fault and teaching them to do it and take pleasure from it, this really frees up lots of things. I myself started with calligraphy out of frustration, because I found it really hard to write. I worked on form so that I could eventually be able to write properly. In the Middle Ages, it was monks who wrote, and only what was of some value: laws and sacred books. Proof that we write what’s important, that writing is always connected with power. People who don’t know how to write lose something.

You’ve done a lot of work for the luxury sector. Which brands would you like to work for?

I’d like to focus more and more on perfume, regardless of the brands. The luxury sector interests me because it allows me to raise the bar, to create outstanding things.

You teach calligraphy. Which three tips would you give a beginner?

Be curious, enthusiastic and passionate. Technique will come later.

What is your vision for the future of calligraphy?

It will evolve as people do. Computers have enabled connections to be made, fostering the growth of a sort of international movement. In 10 years, the Russians have reached an impressive level, the Americans too. There has been a real rediscovery of calligraphy, a vehicle for meaning in society. It must constantly reinvent itself. Calligraphy is an ancient technique but its practitioners must take it forward into the future.

And what are your future plans and ambitions?

I’ve stopped working for lots of agencies. I want to focus more on the artistic world of canvases, pigments and large formats. I’m considering going to live abroad and I’d like to try new things, to move towards projects that are out of the ordinary: bigger, more beautiful, more rewarding.