Table of Contents

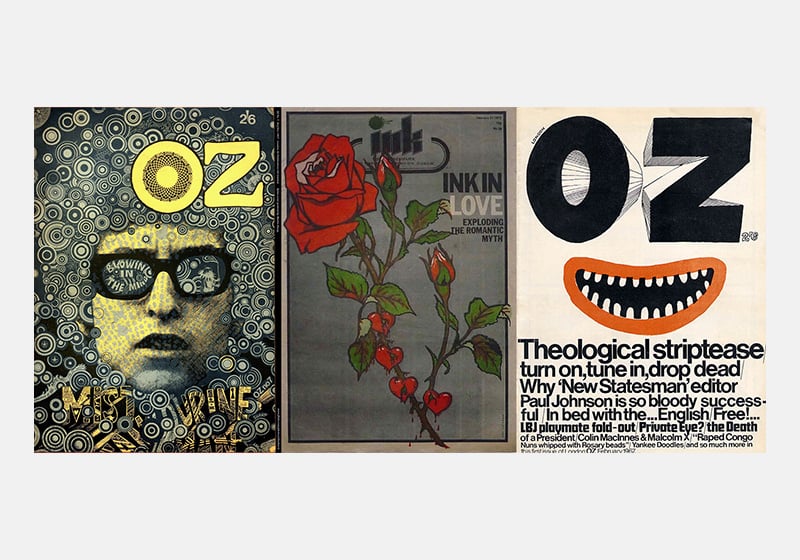

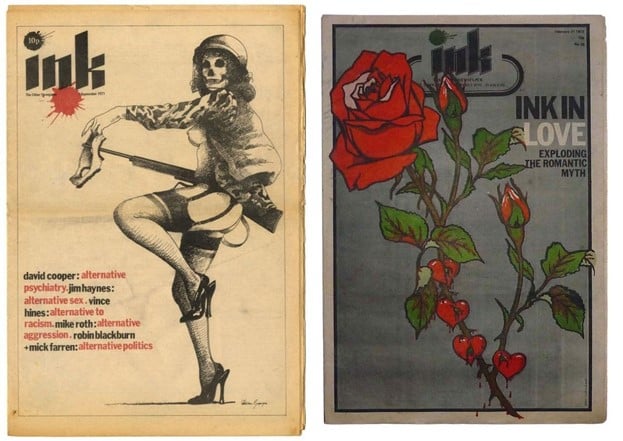

Magazine covers from sixties counterculture

Throughout history, the birth of new aesthetics and original graphic design has often been driven by a variety of very different factors: cultural ideas, social movements and a desire to break the rules, but also the emergence of new technologies and techniques. The 1960s were a case point: in this decade, a number of printing and composition techniques suddenly became widely available, enabling practically anyone to print their own magazine at home.

The results were the incredible alternative magazines of the sixties and seventies: an eclectic mishmash of uneven typefaces, bright colours, hallucinatory illustrations and contributions from cultural icons of the era: from William S. Burroughs to Paul McCartney.

A key innovation that made possible – and in many ways shaped – the aesthetics of this graphic design was dry transfers, like those sold by British firm Letraset. Unlike the rigidity of metal typefaces, dry transfers provided hitherto unseen flexibility in page composition and typeface use. What’s more, these technologies were now available to anyone who wanted to experiment. And so, in homes, garages and classrooms across the world, creatives, writers and graphic designers started producing their own magazines.

The idea was to talk about everything that wasn’t covered by the traditional press. And, above all, to do so without following any graphic design or typographical rules. Let’s take a look at some of the most iconic examples.

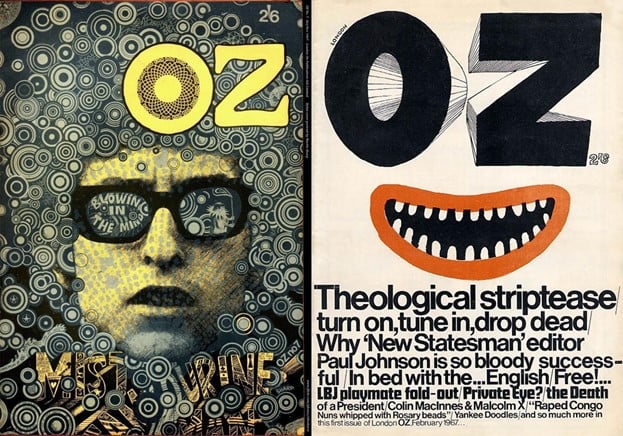

OZ

OZ is one of the best-known alternative magazines from the sixties. It started life as a satirical newspaper in Australia in 1963. Then, from 1967 to 1973 it was printed and distributed in the UK and was much more influenced by the hippie movement and psychedelia.

OZ talked about sex, drugs and politics. And it was fiercely critical of the Vietnam War. The magazine’s content landed OZ in court in what was, at the time, the longest obscenity trial that Britain had ever seen. None other than John Lennon and Yōko Ono came to the magazine’s aid, writing a song called God Save OZ (which later became God Save Us) to raise money for the defence.

Here you can see every one of OZ’s magnificent covers.

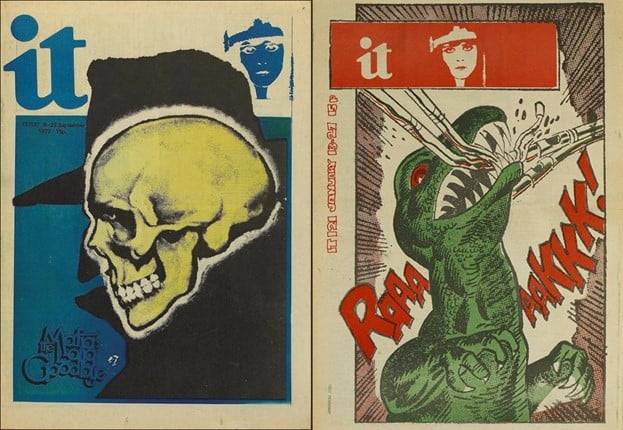

IT or International Times

One of the first alternative magazines to be published in Britain was IT (short for International Times). The first issue came out in 1966 and was launched at a legendary event – the All Night Rave – which was held at the Roundhouse, a disused railway shed in Camden Town, London. The event included sets by Pink Floyd and Soft Machine. You can see the poster here.

Beatle Paul McCarthy was among donors to the magazine. One anecdote perfectly sums up the nonchalance with which the magazine was put together: IT’s logo featured Theda Bara, a twenties silent film star and one of cinema’s first sex symbols; but this image was chosen by accident in a case of mistaken identity: the logo was actually supposed to be of Clara Bow, star of the film It.

The last edition of IT came out in 1973. However, the magazine has been relaunched in various forms since, including in digital format in 2011. Here is an archive of the magazine.

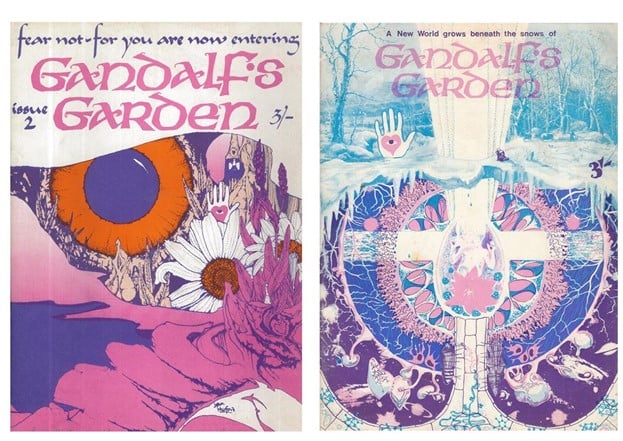

Gandalf’s Garden

Gandalf’s Garden was a magazine that sprang out of the eponymous hippie community based in one of the least fashionable parts in Chelsea, London. Here, the magazine’s creators also ran a unique shop that also served as a meeting point for like-minded people. Just a short distance away, Stanley Kubrick shot a scene from A Clockwork Orange.

Among the many alternative magazines of the era, Gandalf’s Garden was perhaps the most mystical, the most influenced by Eastern religions and the most bizarre graphically. Just six issues were published, with surviving copies now collector’s items that sell for hundreds of pounds.

Ink

Ink was a far more political magazine and, in some ways, more conventional and less “beatnik”. The editorial team wanted to broaden the audience for underground magazines to include part of Britain’s left-leaning middle classes. The experiment was, however, short-lived and in 1972, a year after the release of its first issue, the magazine closed its doors.

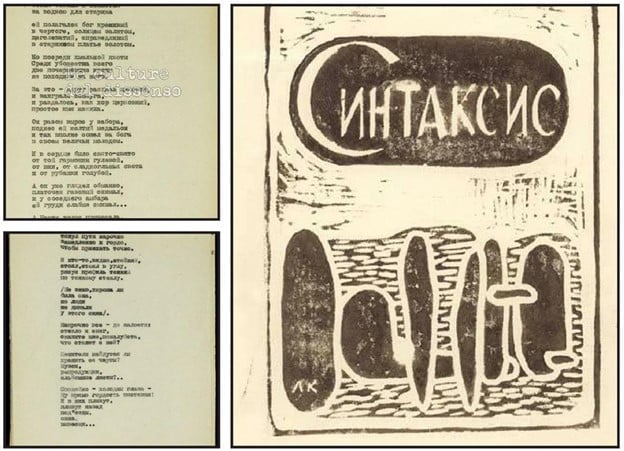

Underground magazines around the world

While the British underground magazine scene was one of the most active and iconic, so much so that 2017 saw an entire exhibition dedicated to it, new technologies meant that anyone anywhere in the world could experiment with content and graphic design in alternative magazines. The Soviet Union, for example, saw the emergence of one of the first dissident magazines, albeit with somewhat conventional graphics: it was called Sintaksis and it was dedicated to poetry.

Meanwhile, in the United States LGBT publications were flourishing, including iconic titles such as Radicalqueen, Effeminist and Gayzette. In Italy, there were countless cyclostyled magazines devoted to music, like Mondo beat, Blues anytime and Freak. It was a similar story in France with magazines such as Actuel springing up in the world of jazz.

If you’re hungry for more, check out this pretty comprehensive list of sixties underground newspapers organised by country, as well as the selection of alternative magazines that’s free to view in the LetterForm Online Archive.