Political posters are a relatively new medium. While the history of advertising posters dates back to the founding of book and art printing in the 15th century, political posters have only been around since the First World War. Designers have been highlighting, criticising, and illustrating political issues ever since. Through posters, they are able to play an important role in mobilising the public for political protests and movements.

Initially employed primarily as a means of spreading political propaganda, the imagery of the poster in its infant decades was often anti-authoritarian – such as in the student protests of the 1960s and the environmental movement of the ’70s, for example.

Those who followed the major political protest movements were united not only by their pursuit of political ambitions and slogans, but also by aesthetics. Today, too, posters should catch the eye. The use and application of posters have, however, changed over time. Indeed, around a hundred years separate the first protest posters from the imagery of today’s protest culture, and it appears that feeds and followers are increasingly displacing advertising posters and wall newspapers. In the past, protest posters were crucial to the launch of movements in the public sphere; today, these movements are partly carried out on the Internet.

Yet certain posters gain more widespread renown for having been shared on social media – they become iconic and end up in the poster archives of major museums. Political posters often employ irony, comparison, and provocation. This results in new designs, which help to draw attention to protest movements. Pre-existing symbols and their appropriations also reappear in motifs. For instance, the clenched fists – one of the oldest examples of protest iconography – have appeared in several revolutions, albeit interpreted differently and with their own imagery.

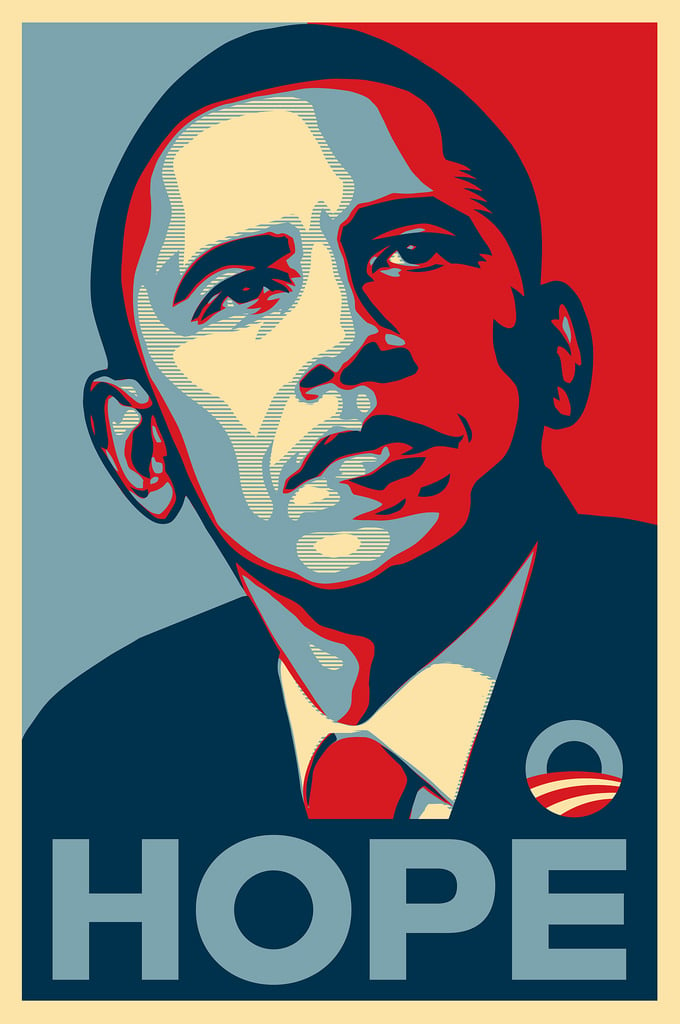

An example of a poster that achieved iconic status is Hope by the artist and graphic designer Shepard Fairey. Fairey seized the initiative, designing the poster to support Barack Obama in his presidential campaign. Today, the work is of course known far more for its motif than for its title: it is based on a portrait of Obama. Mannie Garcia took the original photo, which Fairey then illustrated in the colours of the US flag. Fairey designed the poster and then sold it himself during the election campaign. It became one of the most iconic symbols of Obama’s campaign. Later on, the Obama campaign commissioned Fairey to design variations of his work as well as new motifs, one of which appeared on the cover of Time Magazine.

Following Obama’s presidency, Fairey remained politically active and, barely 10 years later, teamed up with photographer Ridwan Adhami and designers Ernesto Yerena and Jessica Sabogal to design the Greater Than Fear poster series, protesting racism, misogyny, and Donald Trump’s politics. For this project, Fairey uses his motifs to target discrimination; his work depicts a Muslimah, women, and black people – all victims of hostility during Trump’s campaign. The posters were designed for a march against Donald Trump after his inauguration as US president. The aim of the poster series is to show that America has another side to it, different from the one that Trump represents. In his posters, Fairey portrays this in his own way, without using traditional protest imagery like windblown hair and raised fists. To ensure their motifs spread as much as possible, the designers made them available for free online.

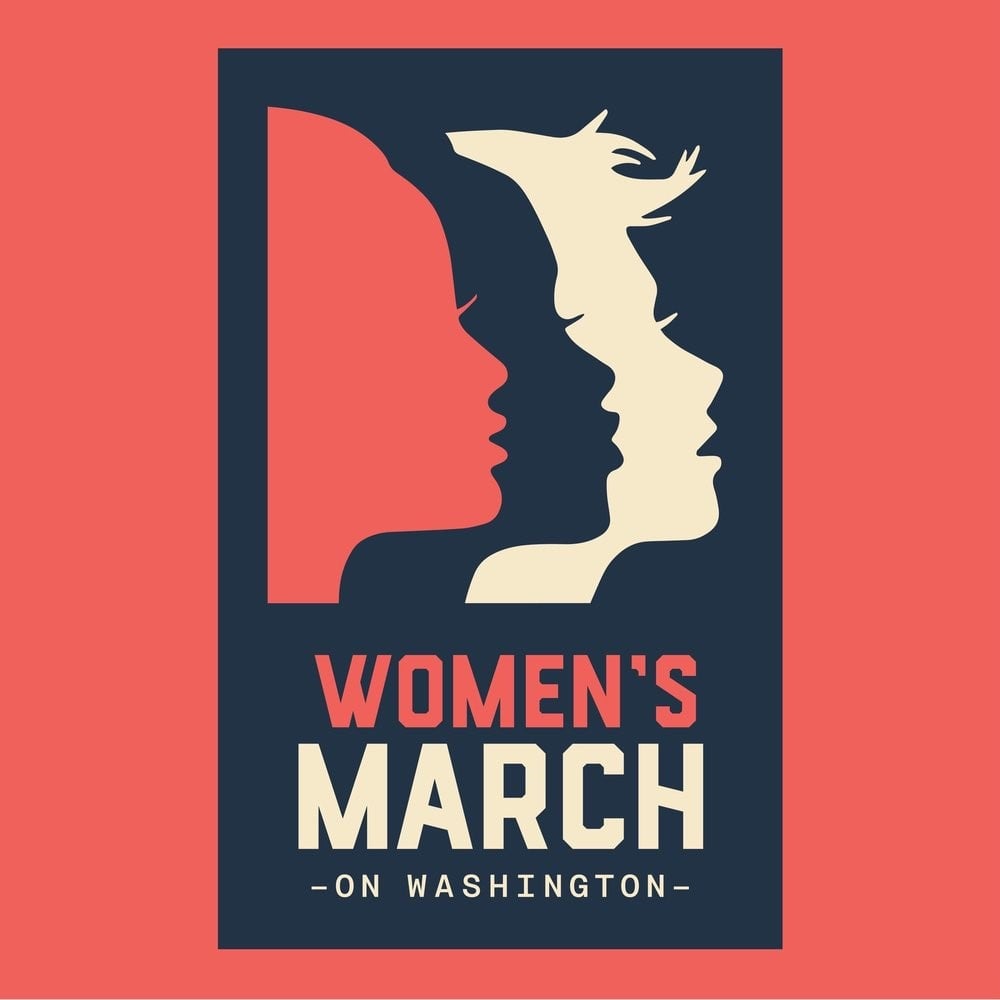

Deva Pardue also made her motif available for activists online. This ensured that her poster achieved widespread recognition, especially online, even before the Women’s March had begun. The poster shows three clenched fists, a popular image in protest movements. Its rapid spread led to a domino effect not only within the design scene, but also among businesses, who duplicated her motif without permission to sell.

In addition to Deva Pardue’s protest poster, there were many other independently designed posters at the Women’s March, a large number of which are now housed in museums. Indeed, in light of the women’s protests in recent years, galleries and museums have rediscovered protest design, dedicating entire exhibitions to the genre. Several posters now belong to the collections of the National Museum of American History and the Museum of the City of New York.

Looking at protest posters, it is clear that the commitment of individual designers and artists plays an important part in bringing public attention to protests. While the posters themselves do not change political conditions, they do aim to encourage people to think, to mobilise, and to effect change and inspire a better future.The official poster of the Women’s March is minimalist, containing only a few colours and using symbols as a stylistic device. It depicts windblown hair as an image of freedom. This motif is also available to download from the official website.