Table of Contents

When talking about UX design, the risk is almost always the same: reducing it to a matter of well-designed interfaces or “good usability”. In reality, user experience is something broader. In practical terms, it defines the way a person moves through a system, understands what they can do within it, makes decisions and completes an action without feeling confused or under pressure.

What UX design is, in brief

UX design (User Experience Design) is the discipline that designs the overall experience a person has when interacting with a digital product or service, taking into account goals, context of use, constraints and expectations.

It does not concern only what the user sees, but above all what they understand, what they expect, and what happens when something goes wrong.

What UX Design includes (beyond the interface)

A well-designed user experience brings together several layers. There is the context in which the user acts — perhaps on the move, with little time, or with a very specific goal — and there are cognitive and technical constraints that influence how they interact. Then there are system rules, content, error messages, response times and support.

UX does not manifest itself in a single screen, but across the entire journey. It is the thread that connects the initial intention to the final outcome.

Why UX Design is so important (for users and businesses)

A poorly designed experience creates friction. Faced with friction, users stop, hesitate, go back or abandon the process. A good UX, on the other hand, often goes unnoticed: everything feels simple and natural, almost obvious.

From a business perspective, this results in fewer errors, fewer support requests, more completed actions and greater trust. From the user’s perspective, it means feeling supported, not tested. A UX that works is a win–win condition: users achieve their goals as easily as possible, while businesses see positive effects on overall performance.

UX vs UI: differences without simplifications

One of the most common questions is the difference between UX and UI. It is a useful distinction, but only if it is not oversimplified.

What UX decides and what UI decides

UX deals with structural decisions: which steps are needed to complete an action, in what order, with which alternatives and what kind of feedback. It is responsible for the logic of the experience.

UI, instead, translates that logic into visual and interactive form: layout, hierarchy, colours, typography, components and interface states.

A concrete example of UX Design

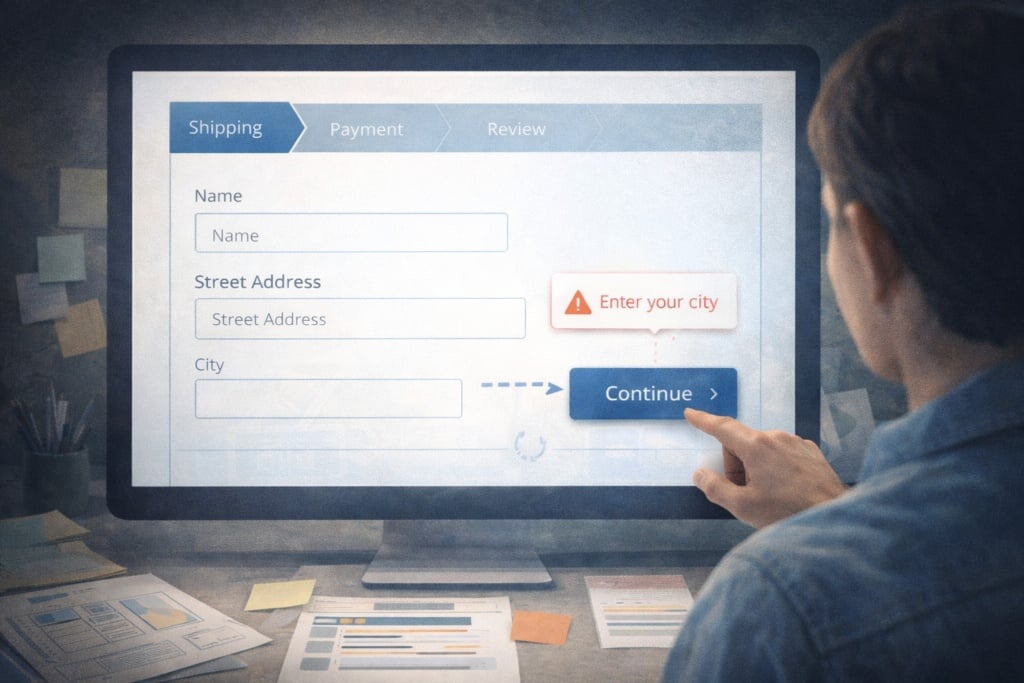

Imagine a user who needs to complete an online purchase.

UX determines how many steps are required, which information to request, when to show costs and delivery times, and how to handle a validation error.

UI decides how those fields look, how readable they are, where attention is drawn and how clear the next step appears.

A common misconception about UX Design

Saying that “UX is functionality and UI is aesthetics” is a shortcut. UI directly influences behaviour and perception, while UX also includes emotional and cognitive aspects. The two disciplines work together and shape each other.

The pillars of good UX

UX works when users do not have to stop and ask themselves whether they are doing the right thing. When what they are looking for is where they expect to find it. When errors do not become dead ends, but opportunities to recover.

In general, an effective experience is useful, usable, findable, credible, accessible and desirable. Not as abstract labels, but as concrete criteria for evaluating whether a project is truly helping the people who use it.

Nielsen’s heuristics: what they are and why they matter

Nielsen’s heuristics are ten usability principles formulated by Jakob Nielsen to identify the most common problems in digital interfaces. They are not rigid rules, but general guidelines that describe how users expect a system to behave.

They include, for example:

- visibility of system status (always understanding what is happening),

- match between system and the real world (using familiar language and concepts),

- error prevention,

- consistency and standards,

- a preference for recognition rather than recall.

Their value lies in their ability to quickly surface obvious issues: unclear steps, missing feedback, ambiguous messages or inconsistent flows.

Nielsen’s heuristics, used properly

Usability heuristics are often treated as a checklist to be ticked off. In reality, they work best as a diagnostic tool: they help identify recurring problems, especially in early stages or during a quick review.

They are extremely useful for removing the obvious, but they do not replace contact with real users. They indicate what might not work; they do not tell you how important that issue is for the people actually using the product.

Accessibility: not an afterthought

When accessibility is addressed only at the end, it becomes a patch. When it is integrated from the start, it improves the experience for everyone. Adequate contrast, clear navigation, understandable text and predictable interactions do not only help users with disabilities: they reduce overall cognitive effort.

The UX process from start to finish

Every UX project starts with a strong temptation: jumping straight to the solution. The process exists precisely to prevent that. Let’s look at how it works, at a high level.

1) Discovery and research

The first phase has a simple goal: understand before deciding. Interviews, data analysis, support tickets and benchmarks help uncover real needs, obstacles and expectations.

A recurring pattern is this: data shows where people stop; qualitative research explains why. All forms of friction that users encounter during the experience of an existing or expected service need to be collected and interpreted.

2) Synthesis and problem definition

Here, information is reorganised. All collected data must be segmented in a coherent and logical way. Insights, needs and frustrations are synthesised into a clear, shared problem statement. Without this phase, the risk is working hard… in the wrong direction.

3) Information architecture and user flows

Before even thinking about visual design, decisions are made about how the system is structured. Content, paths and flows determine whether users will find what they are looking for or get lost along the way.

4) Wireframes and prototypes

Wireframes are used to discuss logic, not aesthetics. High-fidelity prototypes come into play when it is necessary to test comprehension, microcopy and more complex interactions. Introducing visual detail too early often blocks critical thinking.

5) Usability testing and iteration

During testing, the project is put to the test. Users are not evaluated; the system is. Errors, hesitation and misunderstandings are valuable signals: they show where the experience asks too much of the user.

6) After launch

UX does not end with release. Measuring, observing and iterating allow the experience to improve over time and adapt to real behaviours, not hypothetical ones.

Methods and tools: choosing based on context

There is no universal method for designing or evaluating user experience, because every product lives in a different context: type of users, maturity of the service, time and resource constraints, system complexity. Believing that there is a UX “recipe” that always works often leads to using the right tools at the wrong time.

In some scenarios, a few well-targeted interviews are enough to reveal obvious structural problems: recurring misunderstandings, unmet expectations, steps perceived as unnecessarily complex. In other cases, especially when a product has a large user base, quantitative data becomes essential to understand the real impact of a design decision and to distinguish a marginal annoyance from a systemic obstacle.

A recurring example is the redesign of an e-commerce experience. Here, critical points tend to cluster around the same moments:

- product search

- configuration

- clarity of costs

- checkout

Intervening at these key moments — where users make decisions or risk abandoning the process — almost always produces more tangible results than optimising secondary details. In this sense, choosing methods should answer a simple question: where is the experience really being won or lost?

How to evaluate UX

Evaluating user experience means going beyond opinions and observing what people actually do. The most reliable metrics are behavioural:

- how many people complete a task

- how long they take

- where they make errors

- where they abandon the journey

These data clearly show where the experience does not work as intended. However, on their own they do not always explain why. This is where perceived metrics — such as satisfaction, SUS (System Usability Scale) or NPS (Net Promoter Score) — become useful, as long as they are interpreted alongside behaviour and not as absolute judgements.

SUS measures the perceived usability of a system through a short standard questionnaire and is useful for comparisons over time or between solutions, but not for diagnosing problems.

NPS measures propensity to recommend and reflects the overall relationship with a product or brand; it is a general indicator, not specific to UX.

Often, the real leap in quality comes from combining numbers with direct observation: seeing a user hesitate, go back or reread the same information several times says far more than an average score. If data answers the question “what is happening”, observation and testing help explain why it is happening and what to change.

What a UX Designer does

A UX designer works as a balancing point between user needs, business goals and technological constraints. They do not simply design interfaces, but help define the problem, shape solutions and verify their effectiveness over time.

In day-to-day work this means conducting research, analysing data, designing flows and structures, creating wireframes and prototypes, running tests and collaborating continuously with developers, UI designers, product managers and content-related roles. A significant part of the role also involves facilitating decisions: making alternatives explicit, clarifying trade-offs and helping teams choose in an informed way.

The skills that truly make a difference are not only technical. Knowing how to ask the right questions, simplify without oversimplifying, justify design decisions and measure their impact are core abilities. In this sense, a UX designer does not impose solutions, but builds shared understanding.

Common mistakes

Many UX projects do not fail due to a lack of tools or skills, but because of established habits that appear harmless. These are widespread practices, often accepted by convention, that gradually erode experience quality without the problem being immediately obvious.

Among the most common mistakes are:

- Personas built without a real research foundation, often derived from internal assumptions or stereotypes, which end up guiding decisions about a user who does not actually exist.

- Overly guided usability tests, where users are led step by step and the test ends up confirming the team’s expectations instead of revealing real issues.

- High-fidelity prototypes created too early, shifting discussion towards aesthetics when the structure of the experience has not yet been validated.

- Accessibility pushed to the final stages, treated as a corrective add-on rather than a project requirement.

The issue with these practices is not only methodological, but cultural: they shift focus from understanding the problem to validating pre-decided solutions. The result is an experience that works in theory, but generates friction in practice.

Avoiding these mistakes does not mean doing more, but often doing less with greater awareness: dedicating time to research, testing before refining, and accepting iteration as part of the process. It is in this discipline — more than in the tools — that solid UX is built.

UX Design FAQ

UX and UI: which should you study first?

It depends on the goal. If you want to design experiences that work, it is essential to start with UX: understanding users, context, flows and problems. UI becomes truly effective only when it translates an already solid logic.

How many users are needed for a good usability test?

There is no magic number. To identify the main issues in a flow, a small number of well-designed tests is often enough, as long as tasks are realistic and observation is careful.

Is UX useful even if a product already works?

Yes. A product can work and still be tiring, unclear or inefficient. UX helps reduce hidden friction and improve the overall quality of the experience, especially in mature products.

Are UX and business really aligned?

They are when UX is done properly. A clear experience reduces errors, abandonment and support requests, and increases the likelihood that users complete what they start.

Is UX only about digital products?

No. Every service or product has an experience: a journey, waiting times, decisions and friction points. UX principles also apply to physical and hybrid experiences.

UX Design is fundamental

UX design is not a phase, nor a set of techniques applied once a project is underway. It is a way of looking at systems from the perspective of those who move through them, accepting that clarity, simplicity and coherence do not happen by chance, but as the result of conscious decisions.

When it works, UX does not draw attention to itself. And it is precisely in this apparent invisibility that it proves its true value.