Table of Contents

Volta Press was co-founded by Laureen Mahler and her husband John in Oakland, California in 2007. Laureen had previously studied creative writing and John studied literature. Both started printing in 2004 at the California College of the Arts (CCA) because they were immensely interested in books, bookmaking, and literature. Laureen was working as a freelance designer at the time, but it wasn’t until later that design and letterpress became truly intertwined for her. They started their business out of an interest in printmaking methods and typesetting, particularly in the context of book arts.

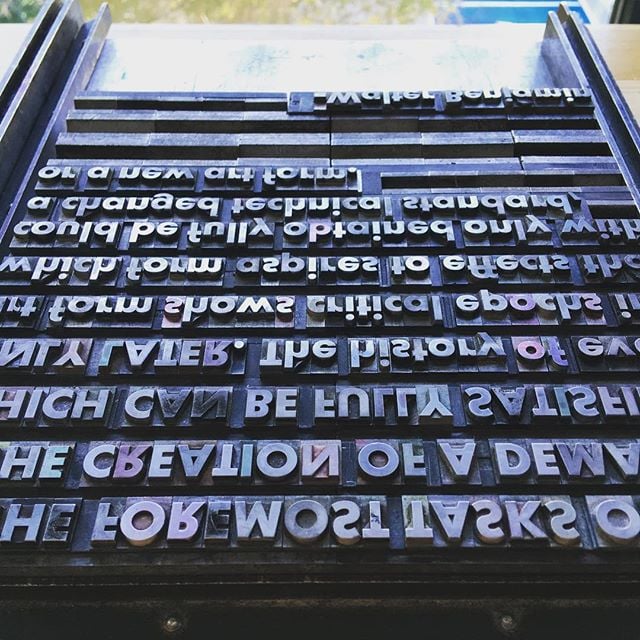

I had the opportunity to meet with Laureen in their beautiful studio and shop in Berlin and chat with her about printing as a craft or as an art, new methods in letterpress printing and much more.

What’s the history of the studio, where are you from and how did you come to work and live in Berlin?

Our first foray into professional letterpress came in the form of a literary journal that we started while I was at California College of the Arts. We essentially wanted to publish work that we liked from people we knew, but we wanted to do it in a unique way. Beeswax Magazine was born from that idea, and we published 8 issues, each with a letterpressed cover and hand-sewn binding.

Shortly after I finished my MFA, John and I started printing on a Vandercook SP15 in the backyard of one of my thesis advisors, Betsy Davids (founder of Five Fingers Press). A short time later, in 2007, we officially started Volta Press and moved into our own space in Oakland, California, where we branched out into both job printing and more experimental letterpress. It’s always been important to us to have a balance between the jobs that pay the bills (which we also enjoy) and printing for ourselves.

In 2010 we had the opportunity to help start the letterpress program at the San Francisco Art Institute, where we subsequently taught up until we left for Berlin in 2014. Teaching letterpress at an art school was an important experience for us because we had students from a wide variety of disciplines who approached printing from a perspective of both intense experimentation and playfulness. It taught us to constantly seek out the ways that traditional and “new” letterpress can coexist and even inform each other.

Leaving the United States had always been in our minds, and in 2014 we decided to pack up and make it happen. We had a few acquaintances here in Berlin, as well as a vague promise of a part-time teaching job, but beyond that, we were just ready for something new. Berlin has a vibrant creative community, as well as a strong foundation for traditional handcrafts, and we found this balance to be very in tune with what we were already doing.

Since moving, we have re-established Volta Press in Berlin Moabit, and I continue to teach letterpress and book design at an arts university here.

In your opinion, have there been any recent breakthroughs in the field of printing?

An obvious answer is the use of sticky-backed nylon plates, though that’s not necessarily recent. In the United States, Boxcar Press really popularized the use of these plates more than 10 years ago. They essentially allowed for free movement between digitally designed files and traditional letterpress methods, plus they offer easier registration and reusability.

More recently there’s been a bit of a resurgence in the availability of new wood type, in both North America and Europe. It’s now possible to design a typeface and have it created in wood on a budget that’s attainable for smaller presses and independent printers. I think these possibilities will only increase as 3D printing and other methods of creating print forms become more prevalent.

Perhaps less concrete but equally important is a shift in the way we think about letterpress: that it isn’t just an industrial craft, or just for ephemera, but that it can also exist in the realm of fine art.

The print methods you use are still very hands-on, but our world is getting more and more digitized – how did digitalization help printers, how did it help the medium print?

As mentioned, the use of sticky-backed nylon plates really bridged the gap between digital design and letterpress.

It’s become easier for designers to realize their work in letterpress, and in turn, many designers have started to push the boundaries of what’s possible in letterpress, registration-wise, design-wise, and otherwise. We find this especially exciting, as it’s also a challenge for us, as printers, to experiment in our own work.

Also somewhat connected to digitization is that online letterpress communities allow printers to connect more quickly and easily, whether it’s to find help fixing something or to share information and ideas.

There’s also the ironic effect that the more digitized our daily lives become, the greater interest there is in hands-on crafts like letterpress. Many of the people (designers and otherwise) who come to us for workshops are super savvy digitally but have little to no experience with hand-printing, and they find the process fascinating.

Which print press do you like to operate most – what would be your dream machine?

We’ve got disparate answers for this one! We learned on Vandercooks in the States, and John prefers the Vandercook for its streamlined roller construction. I’ve become quite fond of the German Korrex and Swiss FAG; though in some ways they feel a little over-engineered, they’ve got a plethora of moving parts that speaks to my love for the mechanics of presses. We’ve also printed with Heidelbergs and C&Ps, and there’s definitely something to be said for the speed and efficiency of platten presses, but ultimately the control of a fully manual cylinder press fits perfectly with our approach to printing.

My “dream machine” would be a cylinder press that has dual platten capabilities – sort of a Rube Goldberg-esque contraption with pedals and knobs all over the place. John is a bit more conservative in this department; he would go for a perfectly maintained Vandercook 3, for its zen simplicity and brass fittings.

You are not just a printer, but very much an artist as well. How much of your work is art, how much is craft, do you even differentiate?

We actually think about this a lot, and we’ve known printers who place themselves very intentionally on one side or the other, whether it’s letterpress as a pure craft, or letterpress as an art form. To be honest, I consider the work that we do to be in both camps.

We strive to come from a place of craft – to me, that means understanding not only letterpress as a technique, but its history, origins, intentions, limitations, and possibilities. We consider how layout, materials, and mechanical processes work together to create the best possible print.

That said, we often do unconventional printing, whether it’s mixing media (plates and letterforms, or digital and analog) or experimenting with non-traditional techniques such as pressure printing. We always have a concept in mind when we’re creating a project, but the success of the artistic aspects depends heavily on the craft behind it.

There are not a lot of female printers out there – do you think being a woman in this industry is mostly helpful or do you think you had to fight more for where you are now?

I’ve been extremely lucky in that from the very beginning I learned letterpress from several great female printers. In that sense, my experience during my MFA and letterpress training was a little sheltered; it never occurred to me at the time that being a female printer was unexpected or less common. As I transitioned into starting my own business and teaching, it became clear that being a female printer was in many ways the exception to the rule. I personally haven’t found this to be helpful, and in an industry that has been largely dominated by men, I think that women have had to fight harder to be recognized as equals. But this is certainly not limited to the field of letterpress. I’m also happy to say that I know and work with a good number of female printers who consistently create exceptional work.

Analogue has recently made a comeback, whether it is Vinyl Records or letterpress printing? What do you think made high-quality analog products become popular again?

Digital fatigue plays a large role in the popularity of analog products, but in some ways, access to nearly unlimited online resources inspires a craving for more hands-on knowledge. I’ve found this to be especially true in the university setting: young designers are eager to truly understand where their craft comes from, and this learning process significantly shapes their output.

Any unexpected mediums that are new to you, what has surprised you in the industry in the last 3-4 years?

Specifically in letterpress, it’s been great to see a rise in the popularity of linoleum and reduction printing as mediums, which has led to increasingly user-friendly carving materials. Beyond letterpress, the resurgence of riso printing is really fun to experience, particularly as it coincides with a trend towards playfulness in both color and form.

How do you see the future of hand printed products and letterpress printing overall?

We strongly believe that there will always be a place for hand printed and letterpressed work. Despite the countless options and lightning-fast speeds afforded by digital printing, the interest in letterpress – whether it’s job printing or workshops – continues to grow. Letterpress programs are popping up in universities, digital designers are seeking out letterpress to enhance their skills, and clients are continually looking for a truly haptic experience.

But the future of letterpress in terms of how it will change in the coming years is, for us, an open question.

It’s a very new concept that letterpress can exist as a fine art, and with this approach comes new ideas, new techniques, and new ways of using the tools we have to create completely unexpected work.

How do you use social media to boost your business?

Our goal with social media is to not only showcase our work but also to communicate with our followers and potential clients. We really strive to curate our accounts, in that everything we post is something that we ourselves would be interested in. Since opening our shop in Berlin, we’ve had a number of visitors who found us through Instagram or Twitter, and it’s always great to see that online connection manifest itself in the real world.

How do you get inspired? Who inspires you?

My first letterpress teacher was Betsy Davids, who founded Five Fingers Press and has taught at CCA for decades. She was not only a mentor and inspiration but also a true guide on how to start a press and put work out into the world.

Our day-to-day inspiration comes from a variety of sources, but we love the work of Karel Martens, Peter Chadwick/This Brutal House, Johanna Drucker, Peter Saville, The Small Stakes, El Lissitzky, and Fortunato Depero. We’ve got a growing collection of Czech and Polish film posters from the 1960s, and we’re crazy about their designs. Otherwise, we get a lot of inspiration from our type catalog: just looking through the cases and seeing what comes from putting letterforms on the press.