Table of Contents

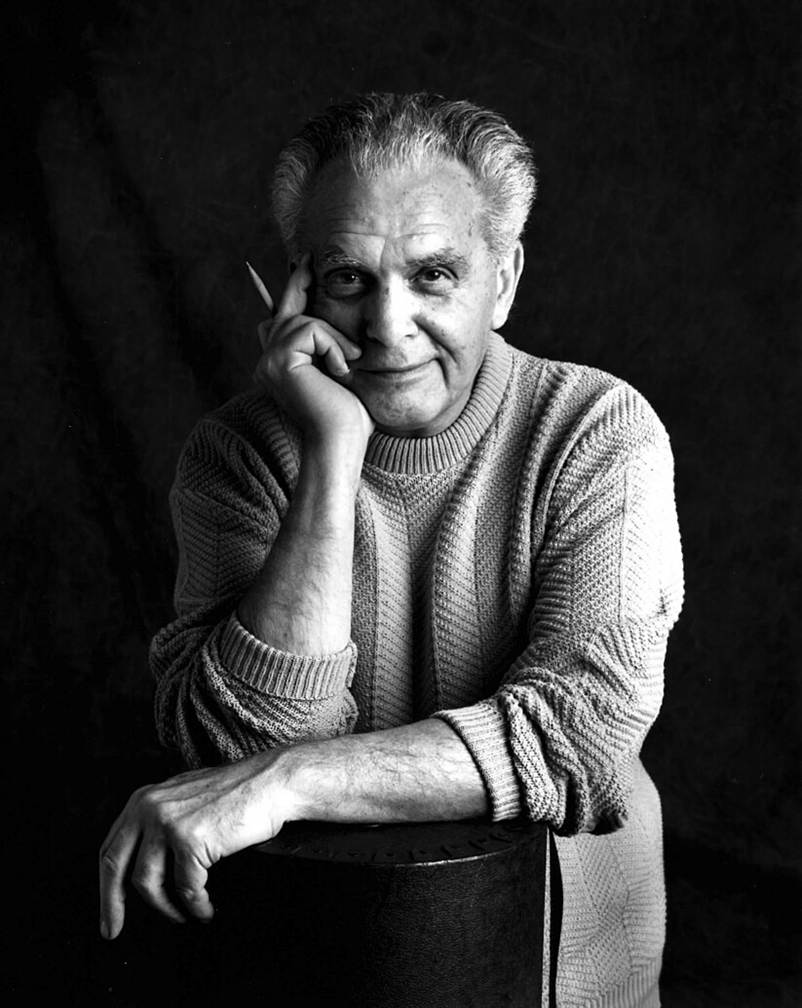

Jacob Kurtzberg, better known as Jack Kirby, was born on 28 August 1917 in New York. He is considered the most influential comic book author and artist in American history – he was a true founding father of US comics, earning him the nickname of the King of Comics (just like Osamu Tezuka in Japanese manga). He was much more than just an artist; he was the driving force that shaped the comics industry during its Golden Age in the 1940s and Silver Age in the 1960s.

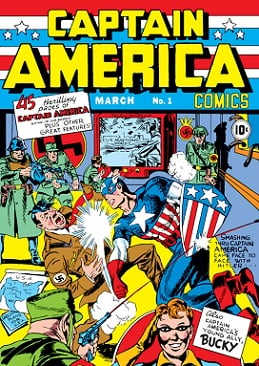

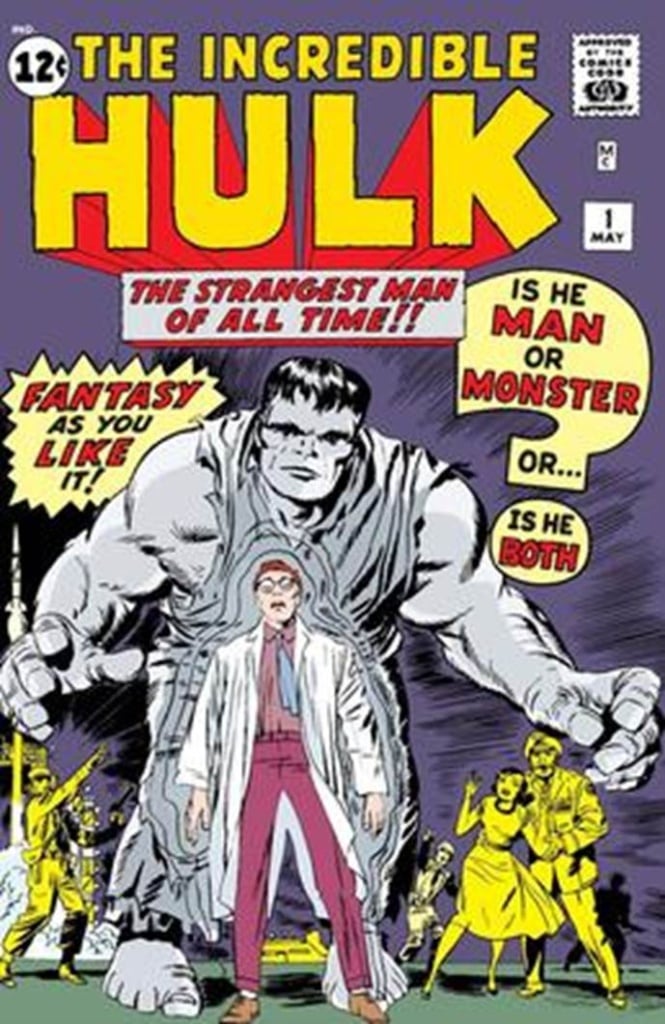

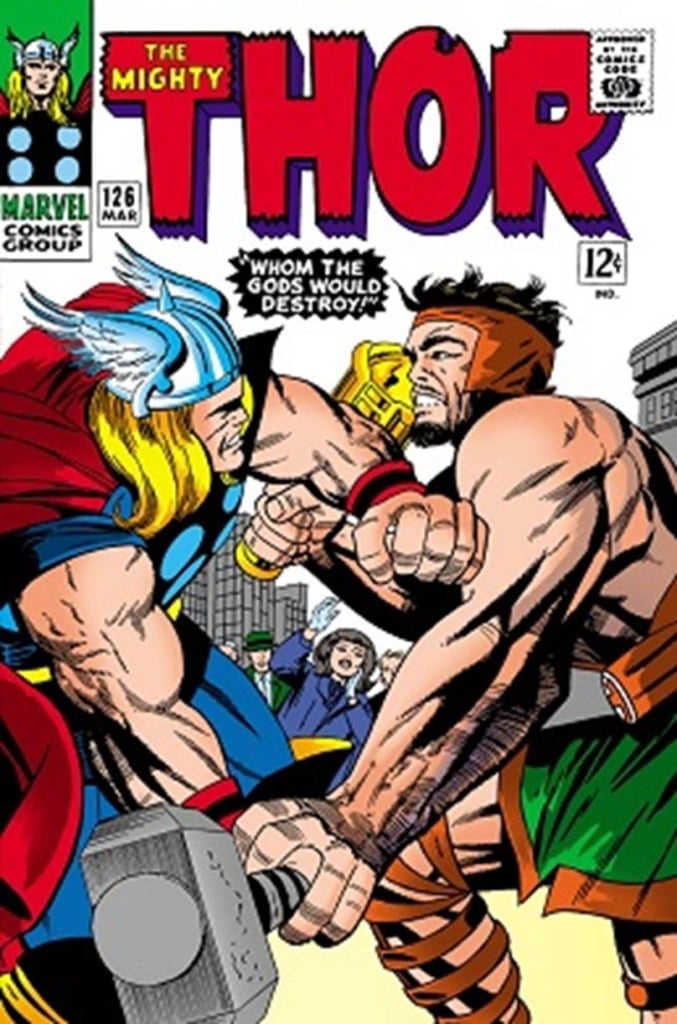

Working alongside Joe Simon, during his long and prolific career he created esteemed titles like Captain America (1941), The Fantastic Four (1961), The Incredible Hulk (1962), Thor (1962), X-Men (1963), Iron Man (1963) and countless other characters that became iconic household names.

It is estimated that he produced over 20,000 pages and 1,400 covers during his career, and he devised his own extremely dynamic and colourful drawing style that still exerts a huge influence over cartoonists worldwide today.

Childhood, influences and early works

Jack Kirby was the son of Austrian-Jewish immigrants, and grew up in a relatively poor household. He spent his childhood on the streets of Lower East Side in New York, where the neighbourhood gang brawls forged his character. As a child, he loved reading the newspaper comic strips by artists like Milton Caniff, Hal Foster and Alex Raymond, and these clearly influenced his own drawing.

Kirby enrolled at the Pratt Institute – a renowned art school – at the age of 14, but left just one week later: the slow pace of learning did not suit his unbelievably vibrant creative instinct! He was therefore essentially self-taught, and mostly learned to draw by imitating the work of other artists.

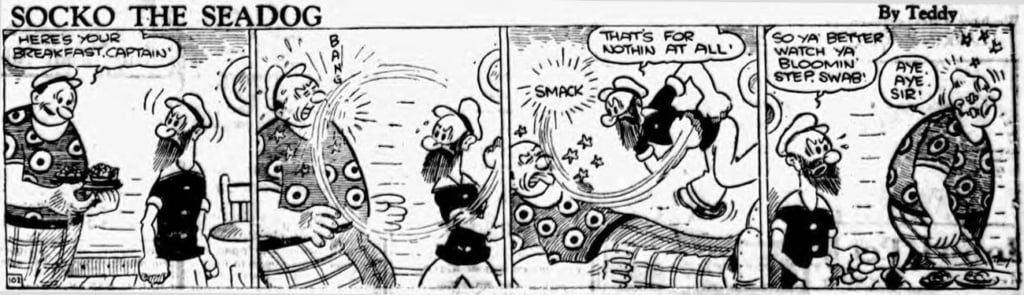

His first paid work came in 1936 for a small newspaper; at the time, comic strips were only published in newspapers. He created funny cartoons under various aliases (Jack Curtiss, for instance) including the clearly Popeye-inspred Socko the Seadog.

He then moved to Fleischer Studios, where he got a job as an inbetweener, drawing the intermediate frames for the cartoons Betty Boop and Popeye. For Kirby this felt like the equivalent of a factory job, but it taught him the cinematic sense of movement that would give his comics their unique style.

His partnership with Joe Simon and the launch of Captain America

Kirby cemented his position in the US comic industry in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He worked for a while, again under a pseudonym, at Will Eisner‘s Eisner-Iger Studio, trying his hand at various genres, including sci-fi with The Diary of Dr. Hayward and western with Wilton of the West.

In 1940 in joined the Fox Feature Syndicate, and it was here that he met Joe Simon. This was a major turning point in his career, and the start of a partnership that continued until 1956. The author decided to abandon his aliases and from then on signed his work simply as Jack Kirby. Most of the work Kirby and Simon created together followed the same process: they both wrote the stories, then Kirby did the pencilling, while Simon took care of the inking and the more business-related aspects.

In the meantime, Joe Simon became art director at Timely Comics (effectively a predecessor to Marvel). Working together, Kirby and Simon spawned comics like the superhero Marvel Boy (1940) and Blue Bolt (1941), but their most famous creation was undoubtedly Captain America, launched in March 1941, a few months before the attack on Pearl Harbour. Kirby drew on his own background when creating the character. The cover of the first issue, in which Captain America punches Adolf Hitler, has gone down in history, while in the stories the Nazi threat is represented by the villain Red Skull.

The comic enjoyed phenomenal success across the USA, leading Captain America to become the first superhero to receive his own publication.

At Timely Comics, Kirby met an up-and-coming young writer called Stanley Martin Lieber, better known as Stan Lee. The duo worked together on Captain America, and then met again several decades later to invent other iconic characters.

The war and the invention of Romance Comics

Unfortunately, these were turbulent years, and in 1943 Kirby was drafted into the US army. He had to quit his job, and became an infantryman, landing on Omaha Beach shortly after D-Day. He used his art skills for the benefit of the army by drawing maps and sketches of as-yet unconquered areas and enemy positions.

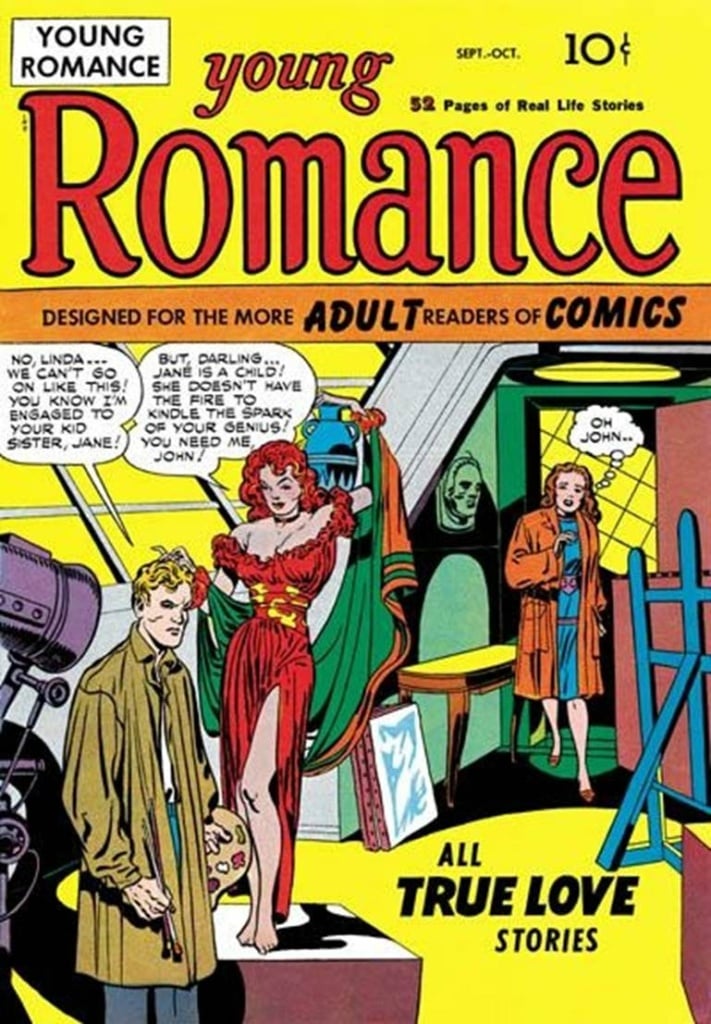

The war was clearly a traumatic event for Kirby, and his subsequent works were clearly instilled with his experiences. He finally made it home in 1945, but by then everything had changed: the American comics market was in crisis, and so he and Simon decided to create stories for a different target market: teenage girls. In 1947 they launched Young Romance, creating a new genre in the process. It sold very well, and showed off Kirby’s incredible versatility: while the panels and drawings were inevitably more posed, his style remained unchanged.

In 1954, Kirby and Simon were some of the first authors to experiment with self-publishing, supported by Crestwood Publishing. They created westerns like Western Scout, war stories like Foxhole and crime works like Police Trap. Foxhole contained tales of war narrated by real WW2 veterans.

Distribution issues and the advent of censorship and the Comics Code brought about the demise of Kirby and Simon’s partnership in 1956. It was the end of an era, but an even more important one was about to begin.

The Marvel boom and the Fantastic Four

During the 1950s, Timely Comics became Atlas Comics, managed by Stan Lee, but by the end of the decade it was on the verge of bankruptcy. Legend has it that Stan Lee begged Jack Kirby to create a comic to boost sales.

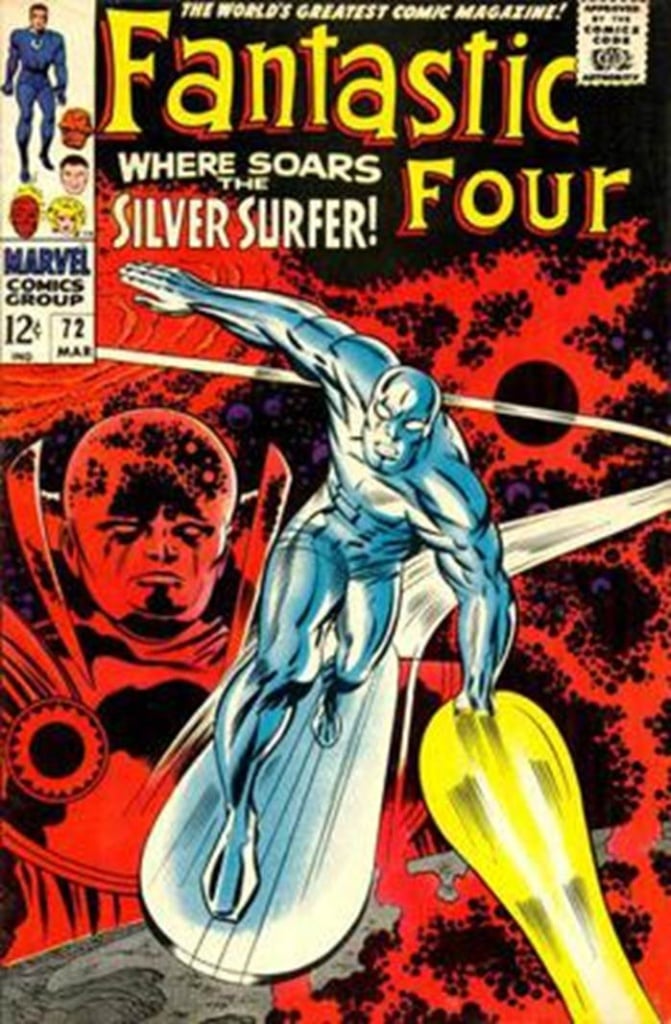

And that’s exactly what happened: the pair created The Fantastic Four in 1961, an iconic series that quite literally saved the publisher, which in the meantime had changed its name to Marvel Comics. Kirby did more than just create a comic, however: he combined cosmic-scale storytelling (with villains like Galactus, who eats whole worlds) with the superheroes’ everyday ‘superproblems’: they were no longer godlike figures, but rather enhanced humans with their own doubts, financial problems, feelings of anger and struggles with raising a family.

Kirby experimented with new visual styles in these comics, producing even more dynamic drawings that seemed to jump out of the page. One innovation was the Kirby Krackle, a technique using black dots the artist had first tested in an embryonic way in Blue Bolt. This is now a his pages with cosmic energy.

The ‘Silver Age’ of American comics officially started in this period.

Thor, Hulk and other iconic characters

After The Fantastic Four, Kirby created a series of characters that are still part of the Marvel universe today, both in comics and at the cinema. The Incredible Hulk first made an appearance in 1962, starring Bruce Banner, a man who – following accidental exposure to gamma radiation – turns into a green giant whenever he experiences emotional stress. The comic explored the fear of nuclear war that was prevalent at the time, and took inspiration from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Kirby’s style reached new heights with Thor, also from 1962: Asgard’s architecture is a mix of futurism and classical art, and the stories blend Norse mythology with sci-fi.

Black Panther followed in 1966; this was an extremely important moment for cultural representation, as he was the first ever black superhero, based in the high-tech nation of Wakanda. Silver Surfer appeared at the same time; although he was initially created by Kirby as an ethereal, cosmic figure, Stan Lee humanised him and turned him into Galactus’ herald.

However, Marvel’s global success led to growing tension between Kirby and Lee. The Marvel Method meant Kirby developed the entire plot and action based on just a rough idea, often including pencilling the dialogue in the page margins. But Lee was credited as the sole writer, with Kirby listed only as an artist. This lack of moral and financial recognition, combined with Marvel’s refusal to return the original drawings, led Kirby to leave the firm in 1970 and move to its rival DC Comics.

His move to DC Comics and the Fourth World saga

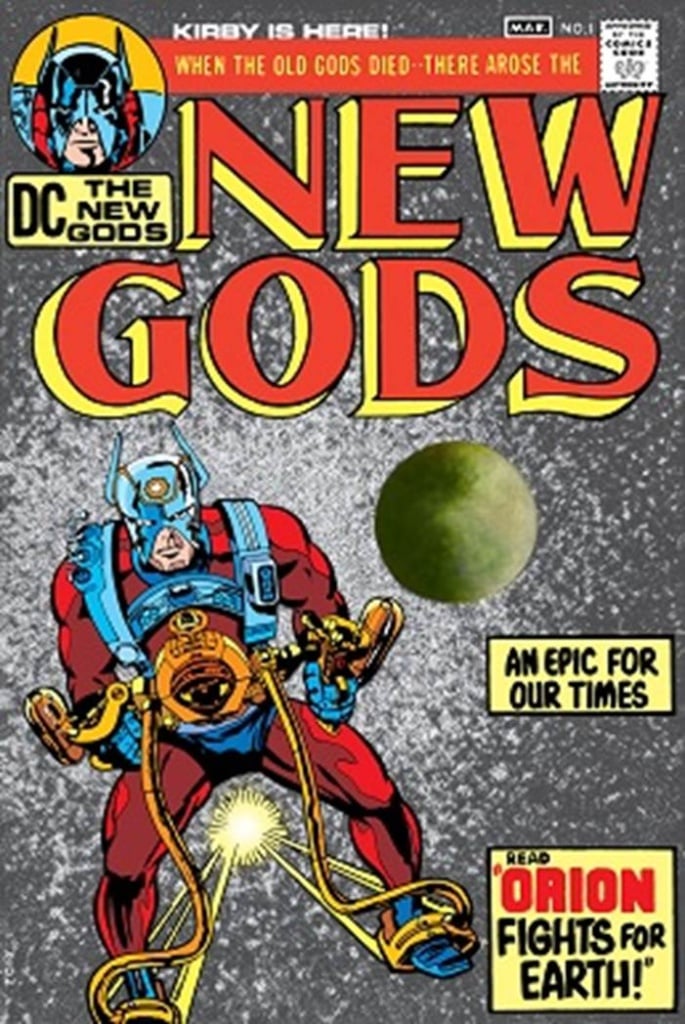

DC Comics’ editor, Carmine Infantino, more or less gave Kirby carte blanche. His first work for DC – on Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen – saved the title, which had been struggling with poor sales. Next, Kirby launched the most ambitious project in his career: the Fourth World saga. in this epic story spread across four titles, Kirby imagined two planets at war with one another: the paradise-like New Genesis and the hellish Apokolips.

This was the peak of his artistic maturity, with storytelling that combined biblical themes and high-tech alien design, mixed with reflection on contemporary society. Although it was a commercial flop and soon shelved, it is today considered one of the artist’s masterpieces. Some of the characters, including the New Gods, outlived the saga and became an important part of other DC Comics-branded stories.

Kirby actually went back to Marvel later in his career, in 1976–1978, to draw issues 192 to 208 of Captain America and to create some new Black Panther stories. In 1976 he launched The Eternals: proof that his creative streak never disappeared throughout his long career.

In the late 1970s, Kirby also made a foray into animation with work for Hanna-Barbera, producing the set designs for the never-released film Lord of Light. In the 1980s, he was one of the first artists to support independent publishers (Pacific Comics and Eclipse), paving the way for the concept of intellectual property rights for artists instead of the work-for-hire system.

Jack Kirby’s legacy

Jack Kirby died in 1994. His style remained recognisable to the end – the thousands of comic strips he drew all contain his trademark explosive dynamism. Kirby shunned the traditional rules of perspective; his characters’ anatomy was not necessarily ultra-realistic, but was focused entirely on movement and action.

He was one of the first to use double-page splashes and to make the characters overflow the panels, creating a sense of narrative urgency. He created the underlying grammar for Marvel comics, and his aesthetic vision is still at the heart of today’s Marvel Cinematic Universe.

At a deeper level, he also showed that a pen can do more than simply create the outline of a character; it can convey unstoppable vitality. He was, and will always remain, the King of Comics.