Table of Contents

Greenwashing and wokewashing

What is greenwashing? And why is it much discussed of late? Greenwashing refers to an abuse of green marketing: it occurs when a company makes claims about its environmental sustainability and social responsibility, but is not able to back these up with measurable data and evidence of real change.

To greenwashing, we can today add another negative trend that’s less well known to the general public: wokewashing (or woke wash). This is where a company adopts ethical values just for show: an awakened conscience in appearance only, designed to improve its reputation, without genuinely honouring the values espoused.

The origins and risks of bogus green marketing

The practice of greenwashing goes back decades; indeed, environmental sustainability has been a hot topic for years now. But with the digital revolution, awareness in the media and general public seems to have accelerated sharply. It’s not surprising, then, that these issues also affect businesses, and that in many cases they are being exploited for marketing purposes.

“Winning over consumers today is not just about the quality of products, but how they fit into environmental and social policies,” explained the vice-president of the Reputation Institute, Fabio Ventoruzzo, in a recent interview with Italian business daily Il Sole24ore. It’s a view echoed by journalist Giampaolo Colletti, an expert in process digitalisation: “75% of teenagers say they would choose a brand because of its commitment to sustainability, regardless of the product or service that it’s selling. Furthermore, these consumers will make up 40% of the market by 2024.”

But the greater the focus on corporate environmental sustainability and social responsibility by the public, the more companies seem to be jumping on the green marketing bandwagon in a way that is often opportunistic and not supported by evidence. When an environmental or social cause is adopted purely to gain favour with a particular section of the public concerned about a particular issue, the risk is obvious: important issues are emptied of meaning day after day, which harms everyone. What’s more, this practice is also counterproductive for businesses themselves, because in a hyperconnected world where it’s not hard to find and share information, the truth tends to come out in the end. There are now numerous cases of big brands being publicly named and shamed for co-opting environmental or social causes simply to bolster their image. Sometimes these accusations can result in genuine crises with serious damage to credibility and reputation.

Examples of greenwashing and wokewashing

When Pepsi is difficult to swallow

In 2017, Pepsi launched a TV and web ad starring the model Kendall Jenner. The unlikely plot saw the celebrity tasked with appeasing a street demonstration by giving out cans of the cola to protestors. It was an attempt by the brand to tap into the zeitgeist by appropriating the issue of social justice. But it turned out to be an epic fail. Its approach to the complex and delicate issues of activism and ethical engagement were seen as too superficial, exploitative and downright incoherent with the firm’s status as a major multinational. Basically, a typical case of woke wash. Among the most critical voices was that of Bernice King, daughter of a certain Martin Luther King Junior. “If only Daddy would have known about the power of #Pepsi” she wrote in a sarcastic tweet that was quickly shared around the world. Under a barrage of criticism, Pepsi withdrew the ad within 24 hours and publicly apologised: “Pepsi was trying to project a global message of unity, peace and understanding. Clearly we missed the mark, and we apologise.” It’s now almost impossible to find any trace of this campaign online.

Gillette: when brand activism is a double-edged sword

At the start of 2019, shaving brand Gillette tried to reposition itself, probably inspired by Nike’s moving campaign featuring Colin Kaepernick. But something went wrong. Very, very wrong. That’s if the number of dislikes on YouTube is anything to go by, which currently stands at 1.6 million compared to just 824,000 likes. With a dislike to like ratio 2 to 1, the Gillette ad is one of the 30 most disliked videos of all time on YouTube. Yet, watching it now, with the detachment that only time can bring, it doesn’t seem so different from the many other campaigns that we’re now accustomed to seeing as part of the trend for ethical marketing or brand activism: the video denounces toxic masculinity, something that remains too prevalent in contemporary society, and urges men to behave better towards women.

So why did it provoke so much outrage? The answer probably lies in the huge disconnect between what the new ad says and the message the brand had previously pushed. The abrupt 180-degree turn away from the claim “the best a man can get” and associations with square-jawed alpha males to images of modern men who are all sensitivity and integrity stretched credulity. The change was too sudden not to arouse suspicions that Gillette was trying to cash in on the #metoo movement with brand activism that was just for show. The result was an unmanageable avalanche of criticism for the brand.

Mastercard, Audi, Mattel: more cases, more criticism

In 2018, for the World Cup in Russia, Mastercard announced that it would be donating 10,000 meals to poor children for every goal scored by Messi or Neymar. But the campaign was a disaster: associating the opulent world of football with hunger brought condemnation from around the globe. Mattel met a similar fate when they launched Curvy Barbie, which was lambasted as an egregious example of wokewashing. The public felt that the toy giant was – thanks to the global success of Barbie – responsible for perpetuating stereotypes of anorexically thin women, which it was now opportunistically promising to fight. Another case? Audi declared that it was fighting the gender gap in a moving ad for the Super Bowl in 2017, but came in for a torrent of criticism when it was revealed that there were very few women in senior managerial roles at the company. It was as if they were saying: we’re all for equal pay and career opportunities, but only at other car manufacturers.

Not all that’s green is greenwash

It is, nevertheless, important to remember that not all cases of brand activism or cause marketing are superficial. During the Covid-19 pandemic in Italy, there have been many laudable examples of firms reconfiguring their production facilities to make a significant contribution to the community. Among the most eye-catching names are Armani, who for a number of months used their garment factories to produce single-use gowns for healthcare workers. Even alcohol producers lent a hand: from Bacardi to Amaro Ramazzotti, many firms converted their production lines to make hand sanitiser. And there’s no harm if these efforts also bring brands positive publicity. In other cases, brands tread a fine line between green marketing and greenwashing.

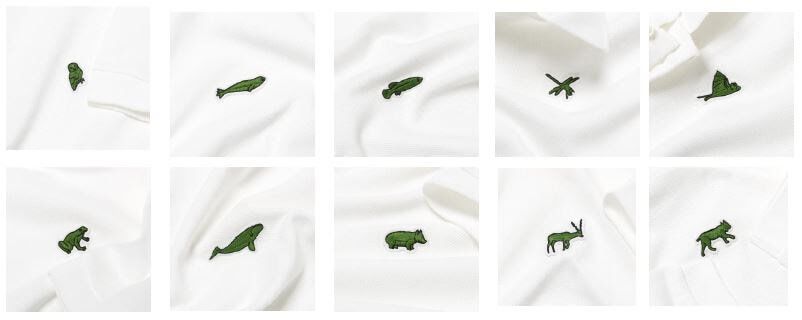

In the case of Lacoste, who we’ve mentioned in the past on this blog, opinion is divided: the brand created a limited series of garments on which the famous crocodile was replaced by endangered species. All profits went to a wildlife conservation charity. The video was widely praised, although this was likely in part due to its creativity and tone of voice. But there was criticism too, because some people suspected the main motive was to build brand awareness with a new demographic more attuned to issues of environmental sustainability.

At the end of the day, the only way to distinguish genuine brand activism (or cause marketing) from an opportunistic and empty PR exercise is the relationship between what a brand says and what a brand does.