Table of Contents

Have you heard of this printing technique? Invented by Louis Dufay in 1930, it was inspired by the iridescence of morpho butterfly wings, and creates a reflective effect. Widely used in the 1960s and 1970s, today it’s become one of the hallmarks of the era and has made collector’s items of books and records that feature the technique.

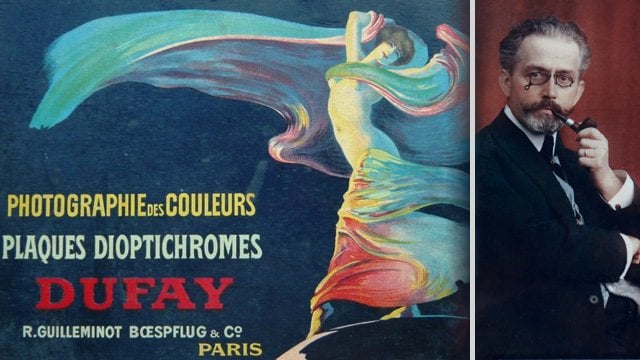

An obscure inventor

Just like the Lumière brothers, Louis Dufay was an inventor from the region of Franche-Comté in eastern France and a pioneer in colour photography and cinematography. Among his inventions are Dioptichrome, for colour photography, and Dufaycolor, for colour cinema. Throughout his life, he created remarkable technical processes for mediating the magic of images, yet he remains a somewhat obscure figure.

The birth of heliophore

An avid butterfly collector, one day, while watching morpho butterflies flutter, Dufay noticed that the ridges on their wings reflected light. So he began thinking about how he could recreate these effects. He eventually succeeded, coming up with a process for printing on sheets of aluminium. Heliophore was born and a patent was filed in 1932. Essentially, this biomimetic technique – in other words, an invention inspired by nature – is an “animation system consisting of metallised colour plates that use the reflection of incident light by a screen with 24 lines per millimetre oriented at different angles to create amazing spatial effects when the medium or light sources are moved,” as graphic design theorists Thierry Chancogne and Catherine Guiral explain. According to them, heliophore is made using “a system of coloured aluminium sheets stuck onto a layer of wax, overlaid onto cardboard and then printed using hand-engraved plastic plates.”

The height of heliophore

Louis Dufay died suddenly in 1936, but his invention lived on and even became extremely fashionable 30 years later. The 1960s and 1970s saw an explosion in kinetic art, the artistic genre in which pieces contain moving parts. This movement can be produced by the wind, the sun, a motor or the viewer. Heliophore was therefore ideal in this era of consumption, space exploration and avant-garde art. It was widely used in decoration and advertising, and, for example, to package things like records and books. In the United States, heliophore was employed to create the visuals for festivals like Woodstock, and was even used by NASA.

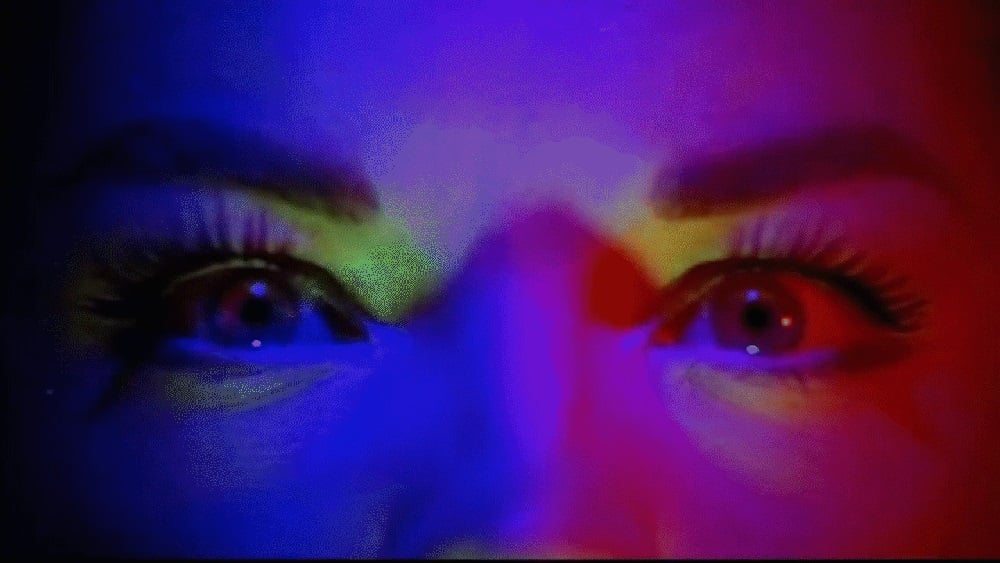

Heliophore in the cinema

In France, Henri Georges Clouzot was one the first directors to use this technique for his unfinished film “L’Enfer”. In screen tests, we see mesmerising, ghostly images of Romy Schneider that show just how visual experimentation and creative vigour were important for both the era and the director. These hallucinogenic images are used by the Clouzot to illustrate the all-consuming paranoid jealousy of Marcel, played by Serge Reggiani, who is the husband of heroine Odette, played by Romy Schneider. Last February, the band Kompromat together with Adèle Haenel released a video paying homage to Clouzot’s film with real bits of heliophore.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6AtwuQSkwgY

In music

In 1967, the Philips record label created the “Prospective 21e siècle” collection of electroacoustic and avant-gardist music. And to illustrate the sleeves of these futuristic records, they decided to use heliophore printing. Today, we don’t know who designed the sleeves, because they weren’t credited, but their remarkable work certainly made a name for this series of records. These slightly mysterious visual effects perfectly represented the style of music, and the limited numbers of records produced sold out in no time at all.

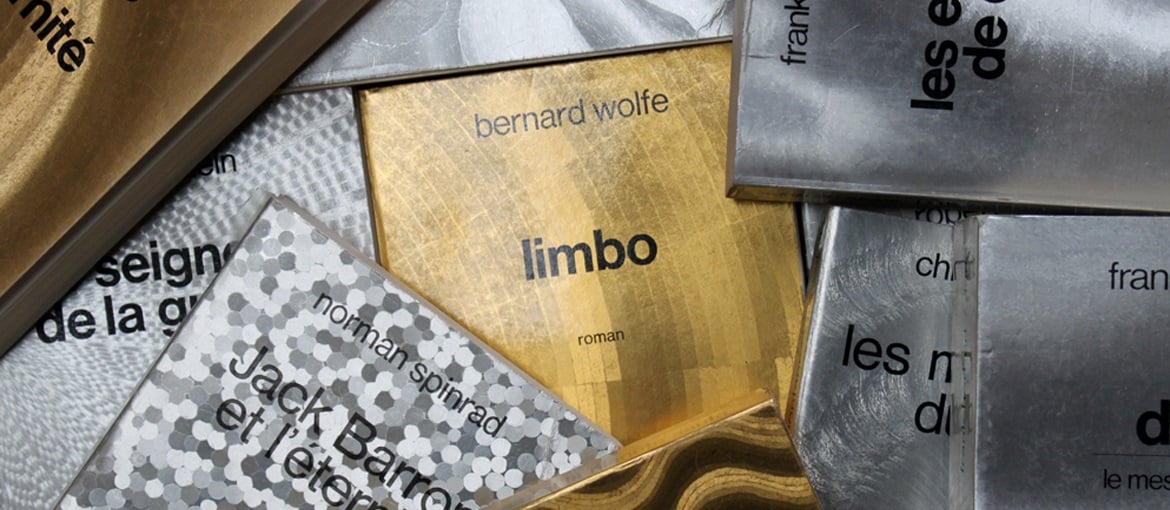

In literature

Later, Gérard Klein, the great French science fiction author and editor, used this technique to illustrate the covers of the “Ailleurs & Demain” collection, published by Robert Laffont. At a time when science fiction was seen as an entertaining but unserious genre, Klein dreamt of “creating a different collection that would show the literary world, one of the most stubborn and conservative I’d ever encountered – and that includes the army and the government, that science fiction could be literature in its own right, that some works could have the appearance and dignity of normal books.” In 1969, publishing house Robert Laffont backed Klein’s use of heliophore for the collection and were rewarded with success. In bookshops, their kinetic covers caught the eye, and came in aluminium, gold or copper.

Collector’s items

Today, the family-run heliophore printing firm Imprim’Hélio no longer exists because, in 2012, manufacturers of aluminium paper set minimum order levels that were impossible for the company to meet. And this means that Heliophore, which saw multiple uses throughout the last century, including album sleeves, book covers and shop decorations, no longer exists either. But this process continues to shine on many surviving objects, which are today collector’s items.