Table of Contents

Are you an e-book convert or an ink and paper stalwart? While the present and future of books divides opinion, it’s worth remembering that today’s revolution is not the first – or even the most significant – in their history.

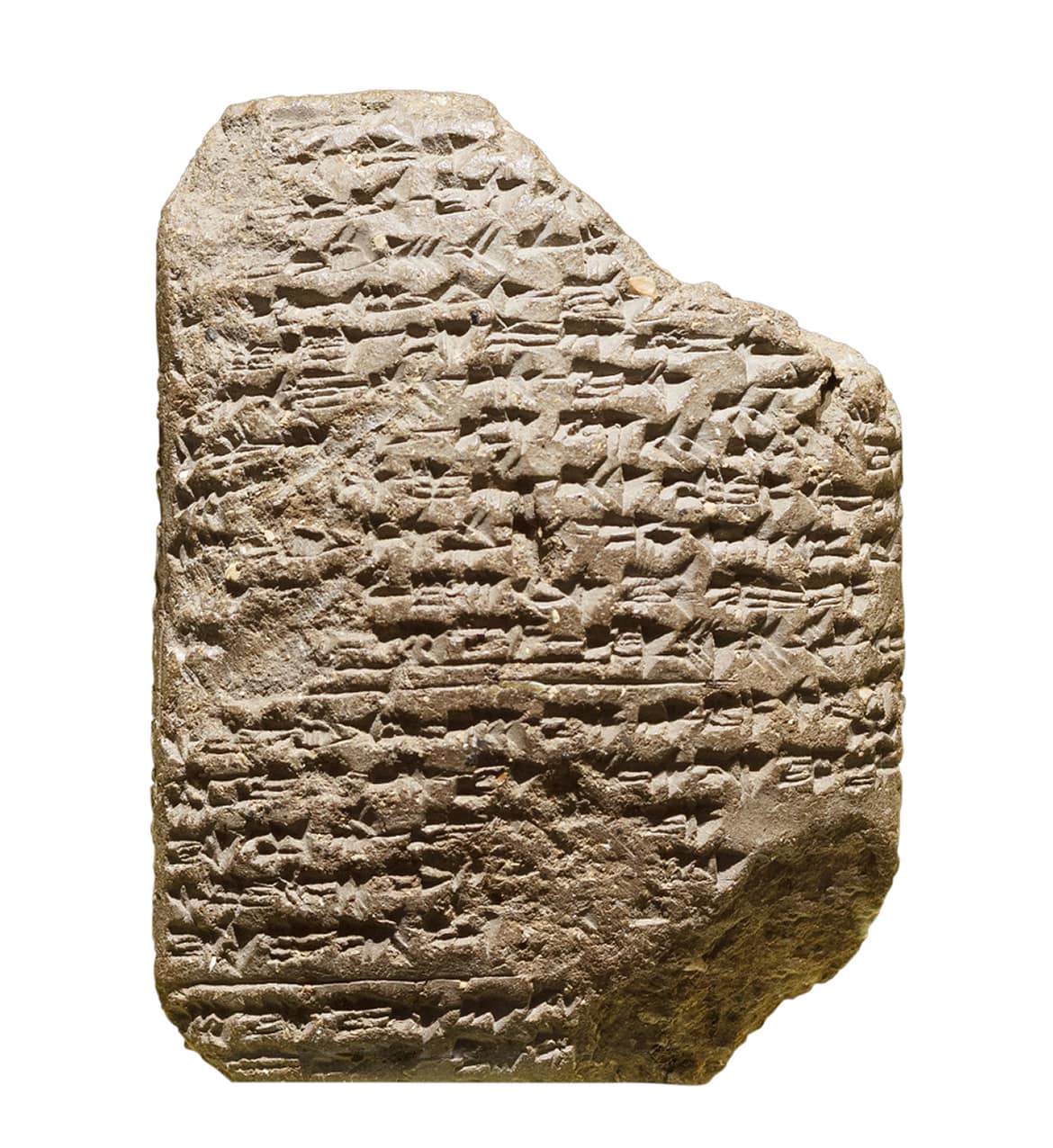

Clay tablets

How were books born? It’s around 4000 BC, so, as you can imagine, we’re a long way from books as we know them today. In fact, before this time, there doesn’t seem to be any evidence of writing. It was the Sumerians, the ancient people who lived in southern Mesopotamia, who invented the first known writing system: cuneiform. They used pointed instruments to carve signs into clay tablets which were then left to dry. These engravings were wedge-like, hence the name “cuneiform”, which means “wedge-shape” in Latin.

Papyrus scrolls

We have to take a big leap forward in time before we see the first rolls of papyrus. The earliest archaeological evidence dates to 2400 BC and originates in Egypt. This paper-like material was obtained from the pith of the papyrus plant, which grew along the banks of the Nile. Once it had been extracted from the stem, the pith was cut into strips, pressed, glued and dried. The result was a sheet on which you could write with a sharp quill made from a reed. Single sheets were then glued together to form rolls that could reach up to 16 metres in length. Text (written on the inside of the roll) was arranged in columns several centimetres wide.

Papyruses were rolled up and stored inside wooden tubes. They weren’t the most practical things to read: papyrus scrolls were wound around cumbersome wooden poles and had to be unrolled with both hands. And there was another drawback: papyrus is a fragile material that wears easily and doesn’t like moisture. When taken out of its native climate, the warm and temperate Mediterranean basin, it rots easily.

Parchment

Around the 2nd century BC, a new writing material appeared: parchment, a membrane made from animal skin that has been limed, cleaned and stretched. The result is a thin, very smooth, strong and elastic surface. To this day, the very finest parchment is still considered one of the best materials for writing on – it’s no coincidence that parchment was widely used up to the 14th century AD.

But where did it come from? In fact, the material originated in Ancient Greece. The word “parchment” derives from the name Pergamon, an ancient Greek city that once boasted one of the largest libraries in the world, rivalled only by the Great Library of Alexandria. As papyrus became increasingly scarce, parchment represented an ideal alternative.

Wax tablets

In Ancient Rome and Greece, the advent of wax tablets offered a far more practical alternative to more traditional writing materials. They consisted of small blocks of wood covered in layers of wax. A stylus (made from wood, metal, bone or ivory) was used to engrave the tablets, which could be scraped clean and re-used. In another innovation, tablets (which bear a striking resemblance to today’s electronic iterations) were joined together at one edge with a piece of string or wire to create an early a predecessor to the ring binder or bound book.

The codex

We’ve now reached the biggest revolution in the history of books. A revolution which, just like the one we’re experiencing today, aroused mixed feelings in readers. The Romans called it the “codex”, a word that derives from the Latin “caudex” (meaning bark or tree trunk). Codices looked like books as we know them today: they comprised a protective wooden cover (or sheets of papyrus or parchment), inside which were held sheets of papyrus with writing on either side.

The great innovation lay in the format’s convenience: codices were compact and easy to browse with page numbers and indices that aided reference.

Despite this, many, including pagans and the Jewish people, remained deeply wedded to the traditional scroll and viewed the codex with suspicion. On the other hand, the Christian community enthusiastically embraced this new technology and monks began busily transcribing prayers and sacred texts onto codices. And thus Christianity would play a key role in the success of these “new books”, which were crucial for spreading literary works in the Middle Ages.

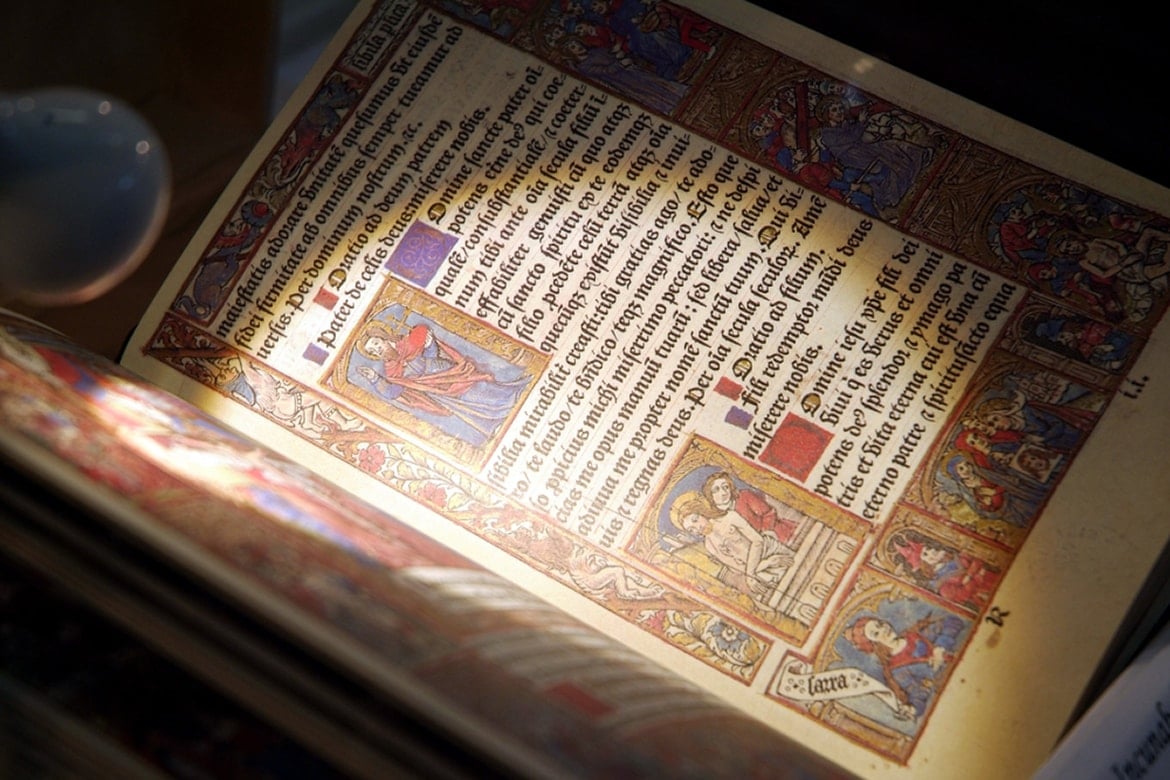

Illuminated manuscripts

It’s worth remembering that, by 105 AD, in faraway China, Cai Lun had already invented paper. Yet there would be a long wait before the bound paper book was invented. In around 400-600 AD, the first illuminated manuscripts appeared on sheets of parchment. They were hand-written, decorated with precious materials like gold and silver, coloured with bright dyes and embellished with elaborate illustrations.

Works of art in their own right, these manuscripts were also of fundamental historical importance: had they not been transcribed onto illuminated codices, many of Ancient Greek and Roman works of literature would have been lost forever.

The first printed book

Much of the history of books is bound up with the history of printing, which began in the 6th century BC when the Chinese invented the first printing system using blocks of wood. With characters carved into them, the blocks were covered in ink and pressed onto a sheet of paper, like a stamp. One of the first texts printed using in this printing method – or, at least one of the oldest existing examples – is a copy of the Diamond Sutra, which dates to 868 AD, a five-metre-long scroll comprising six sheets of paper.

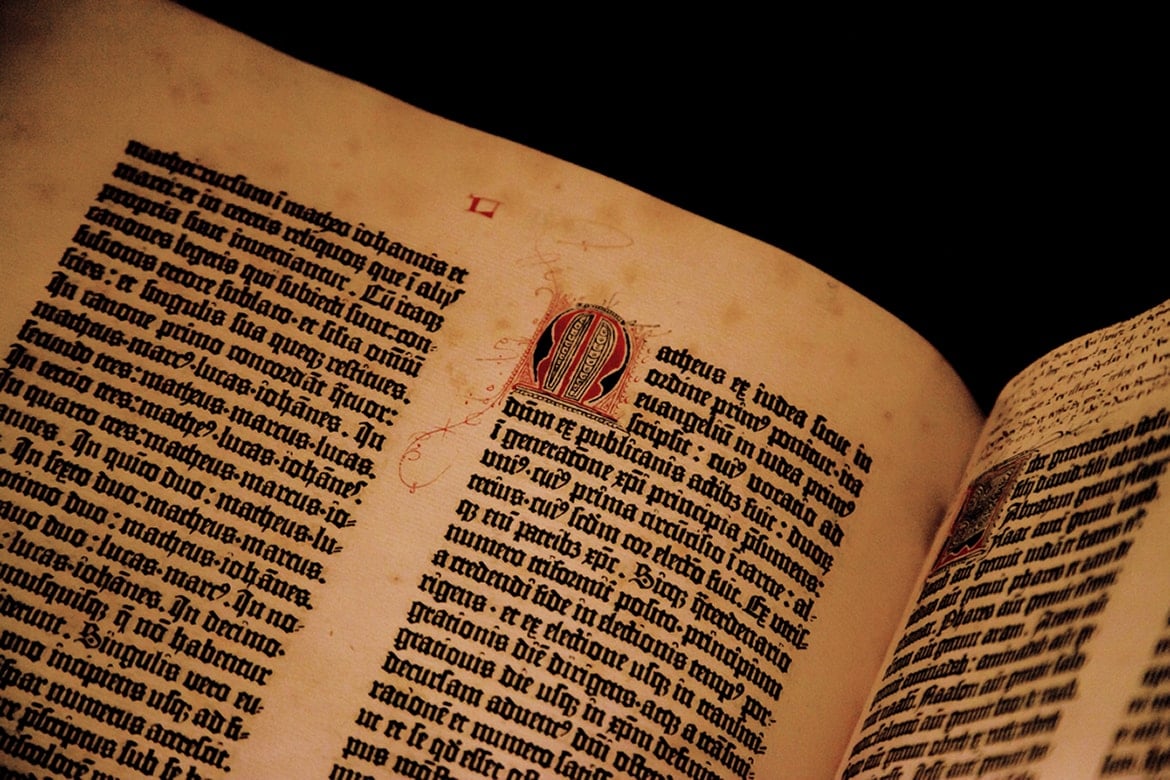

Movable type and the Gutenberg Bible

We’ve arrived at another decisive point in the history of books and, perhaps, the most important in the history of printing: the invention of movable type. We’re still in China, because it was here in 1041 that printer Bi Sheng invented clay movable type. The invention was subsequently improved upon when, in 1298, Wang Zhen swapped clay for wood and created a system of revolving tables that improved print quality. But it was German goldsmith Johannes Gutenberg who perfected this system and introduced it to Europe. The first book printed with this new machine was the Gutenberg Bible, with the first of 180 copies printed on 23 February 1455. Only 20 or so of these survive today.

If you want to learn more about different printing techniques, we recommend reading our article: A brief history of printing. From the 15th century to today. But here we’ll limit ourselves to the enormous impact that this invention had on the history of books: production costs and times fell drastically, while print runs increased, as did the number of people who could access books and the knowledge within them. Indeed, by the end of the 15th century, printing had spread to more than 200 European cities, and over 20 million books had been printed.

Pocket-sized classics

The year 1501 saw the first pocket-sized classics published in Greek and Latin. Aldus Pius Manutius was an Italian publisher, grammarian and humanist, remembered for two innovations: he introduced the pocket-sized format – small and affordable books – and the italic typeface, whose compact letters saved space. Thanks to these inventions, more “gentlemen” could own books and, what’s more, carry them in their pockets to read when and where they liked.

The e-book era

Our journey ends with another great leap forwards, this time to the 1970s, the decade that saw the very first e-books created as part of the Gutenberg Project. For a number of years, digital books were produced for a single purpose: to preserve notable works of literature for posterity, mainly books in the public domain. It wasn’t until the 21st century that the digital format began to be used for publishing new titles: in 2000, the first original e-book was published, Stephen King’s “Riding the Bullet”. It sold over 400,000 copies in a single day. Then, in 2007, Amazon brought out the Kindle, the first e-book reader. It was an instant hit with readers.

Today, the e-book era is well and truly underway. But this doesn’t mean that ink and paper books are on the verge of extinction. Printed books continue to coexist alongside their digital cousins, their inimitable feel and smell holding enduring appeal to readers.