Table of Contents

Igor Tuveri, AKA Igort, was born in Cagliari, on the Italian island of Sardinia, in 1958. Over a long career spanning comics, screenwriting, music and cinema, he has worked around the world, and was one of the first Italians to collaborate directly with a Japanese publisher.

More than a comics artist, Igort is an explorer of visual and narrative languages who has left an indelible mark on culture in his native Italy and abroad.

Starting out in Bologna’s avant-garde art scene in the seventies and eighties, Igort embarked on a personal and professional journey that would take him into the heart of Japanese culture, before bringing him back to Italy to play an instrumental role in popularising the graphic novel as a genre.

In his life, Igort has travelled the world, absorbing the cultures and customs of the places he has visited. And in his art, he has interwoven experimentation in drawing with a constant quest for new forms of expression and storytelling, inspiring generations of readers and artists along the way.

A childhood steeped in Russian culture

Igort’s Sardinian roots are definitely present in his work, albeit beneath the surface. But growing up, it was the culture of somewhere quite different that influenced him most: Russia. His father loved the country’s classical music, while his grandmother introduced the young Igor to Russian literature before he could even read, entertaining him with stories based on the classic novels of Chekhov, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

This early introduction to the emotional depth and narrative complexity of the great Russian novels would leave a lasting impression and shape his own approach to storytelling.

As well as a love of literature, Igort developed a fascination with drawing and visual arts from a young age. Among his greatest influences were Winsor McCay’s poetic and innovative cartoons, and the expressionist paintings of Lyonel Feininger.

In the avant-garde with Valvoline

In 1979, at the age of 20, Igort left Cagliari for Bologna. There he found a vibrant cultural scene, and wasted no time making connections and starting collaborations, while also experimenting with different forms of artistic expression, from illustration to music.

Yet he always came back to comics: in 1980, his first published work appeared in the pages of Linus magazine, the biggest and most prestigious showcase for Italian auteur comics.

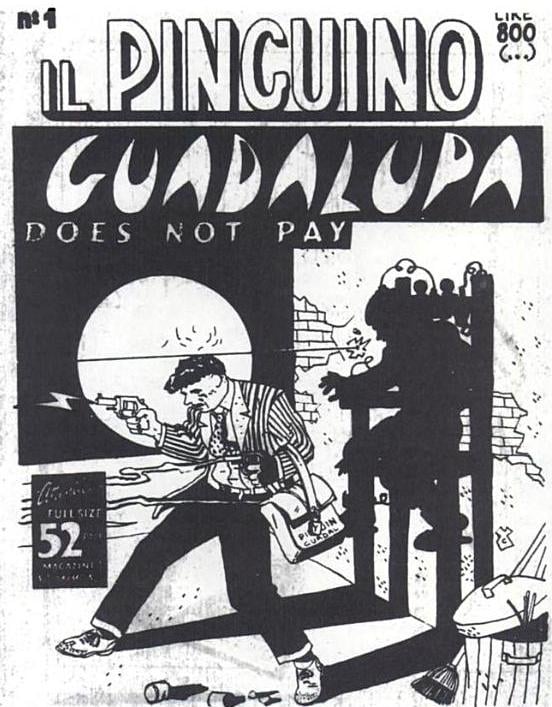

Il Pinguino Guadalupa (self-published)

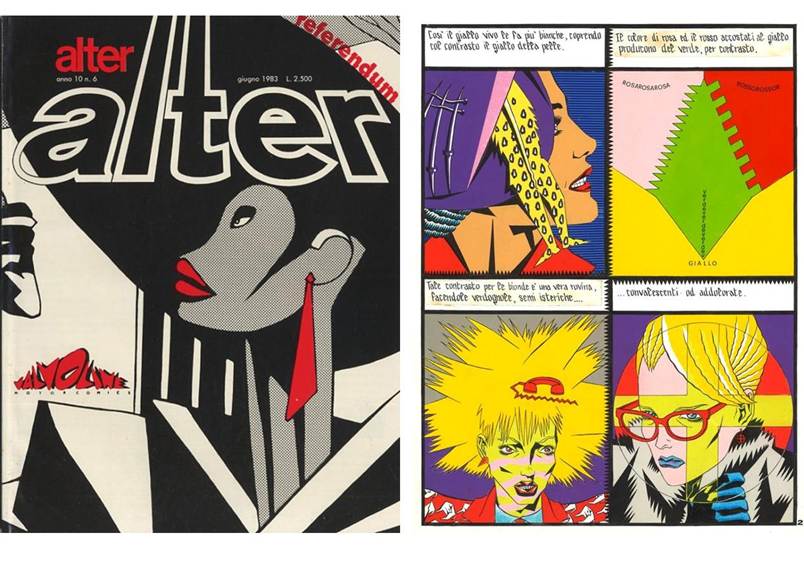

But it wasn’t until the early eighties that Igort really made his mark on Italian comics. First, he launched the self-published magazine Il Pinguino Guadalupa. Then, in 1982, he and fellow artists Daniele Brolli, Roberto Baldazzini (with whom he’d previously worked on Il Pinguino), Lorenzo Mattotti and Giorgio Carpinteri founded the avant-garde art collective Valvoline, together with Marcello Jori and Jerry Kramsky. They were later joined by Massimo Mattioli and Charles Burns.

Valvoline were revolutionary in blending existing genres and techniques to create new ways of storytelling. They published their first comics in Alter, a supplement to Linus magazine. Entitled Valvoline Motorcomics, it was a sort of magazine within a magazine. Later, they also had their own section of Frigidaire magazine, called Valvorama.

But Valvoline didn’t confine themselves to comics: they also worked in design, painting, fashion and music, such was their creative vitality and desire to blur the boundaries between different artistic disciplines. In doing so, they caught the eye of Art Spiegelman, who published some of their output (Carpinteri’s mostly) in Raw Magazine.

Early work and musical career

Alongside his work in comics, Igort led a parallel a career in music. In 1980, under the pseudonym Radetzky e gli isotopi, he released his first solo album for the Italian Records label. Then, in 1985, Igort staged the musical Melodico Moscovita at Valvoline Blitzkrieg, a major Valvoline exhibition held in Geneva. It marked the European debut of Slava Trudu!!, a band in which Igort was lead singer and composer.

Next, Igort turned a new page and went to live in Paris. Restlessness would be a constant in the career of the artist, who moved from city to city in search of new adventures and inspirations. In the eighties, Igort began working for major French publisher Les Humanoïdes Associés. He also served as artistic director for the monthly magazine Dolce Vita, which he co-founded with Oreste Del Buono, at the time the editor of Linus and Alter.

The Japanese nineties

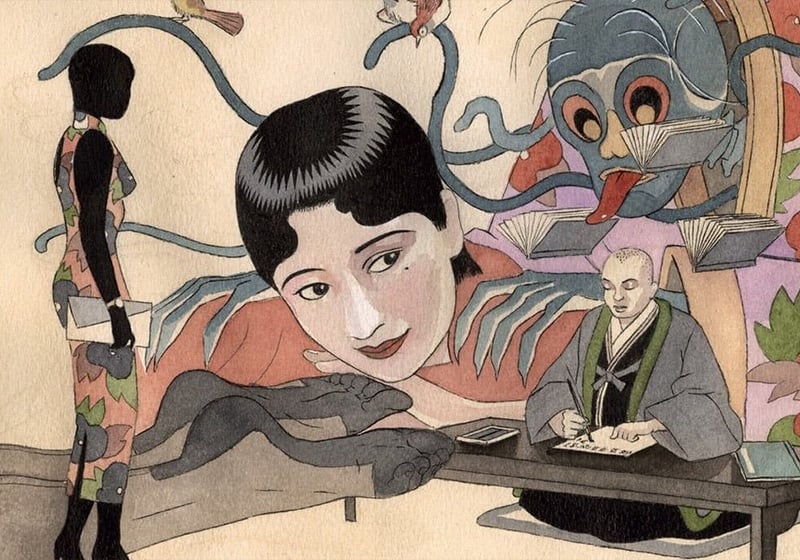

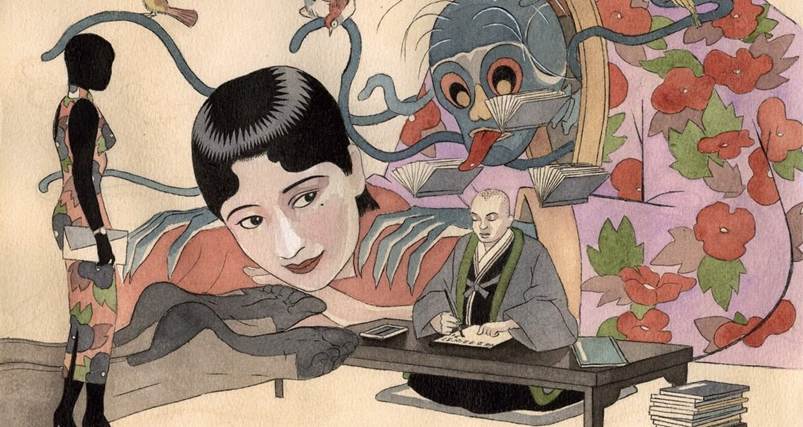

A change in direction in Igort’s comics came in the early nineties, when he came into contact with Japanese publisher Kōdansha. Their partnership was cemented in 1994, after Igort won the Morning Manga Fellowship, a sort of scholarship that allowed him live in Japan and work with editor Tsutsumi Yasamitsu.

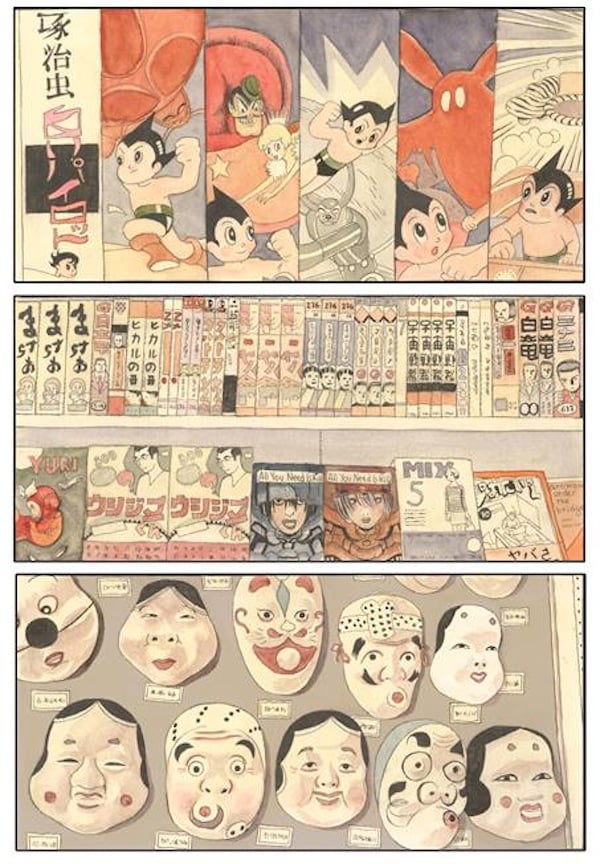

Igort was one of the first European authors to publish his work directly in Japan, which, at the time, was a market all but closed to Western authors. The Italian was fascinated with Japan, which he described as a world where “seemingly simple signs concealed a mysterious wisdom”. Plying his trade in Japan meant exacting work schedules and a meticulous approach to publishing, but Igort showed an impressive ability to adapt and developed a deep understanding of manga storytelling.

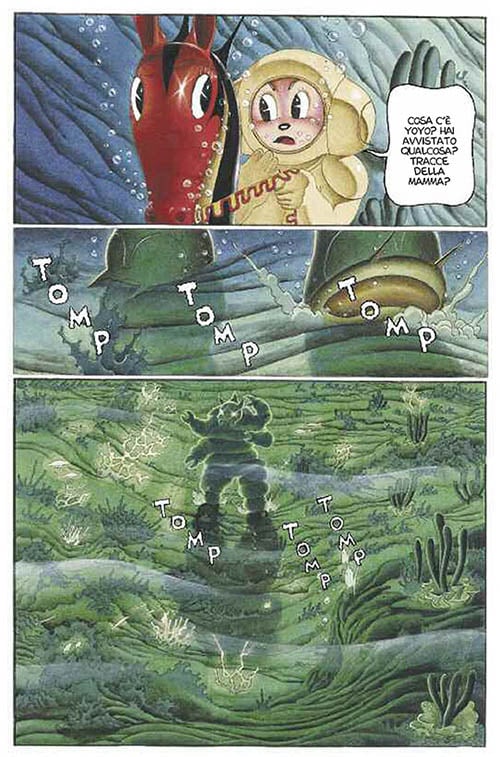

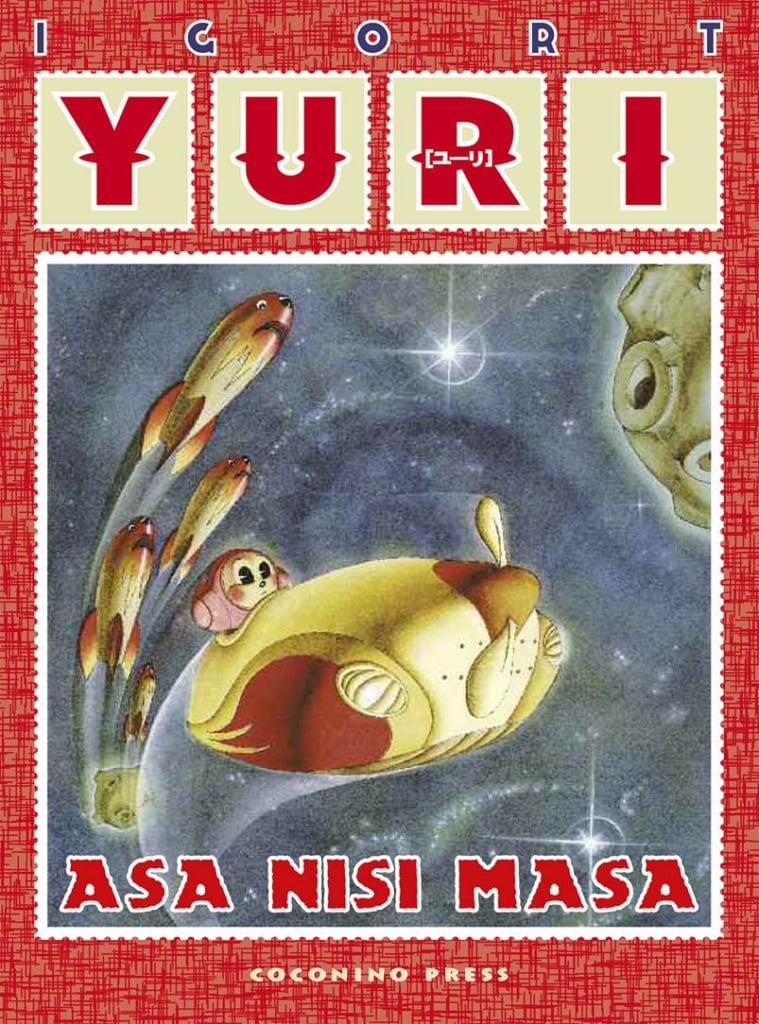

For Kōdansha and other major Japanese publishers like Brutus, Igort produced an eclectic mix of work. Highlights include a series set in Sicily, Amore, and another about a child cosmonaut, Yuri. The latter was released in weekly episodes in Kōdansha’s Comic Morning magazine, which at the time sold 1.4 million copies a week.

The character Yuri was wildly popular, so much so that in 1992 he featured on Swatch watch, which in turn became a bestseller. Years later, Yuri returned in a comics series published in Japan. Little Yuri is a four-year-old cosmonaut who, with his robot Uba and computer Bozo, travels the galaxy in search of his parents. In the series, Igort takes a deft and sensitive look at orphanhood, an especially emotive subject in Japan.

In the artist’s prolific stint in Japan, he wove himself into the country’s cultural fabric, collaborating with musician Ryūichi Sakamoto on a story published in both Japan and Italy, and earning the admiration of world-renowned artists such as Jiro Taniguchi, who would become a friend.

This was a fertile period of learning and experimentation for Igort, one that would profoundly influence his narrative and visual style. Years later, he would reflect on this life-changing experience in The Japanese Notebooks, an autobiographical trilogy of graphic novels.

The graphic novel arrives in Italy with Coconino Press

On returning to Italy in 2000, Igort began a project that would be instrumental in popularising a new genre of sequential art on the peninsula: with Carlo Barbieri, he founded publishing house Coconino Press. Its mission was to bring a wider Italian audience to the graphic novel, a more complex and adult-oriented format that was already taking off abroad.

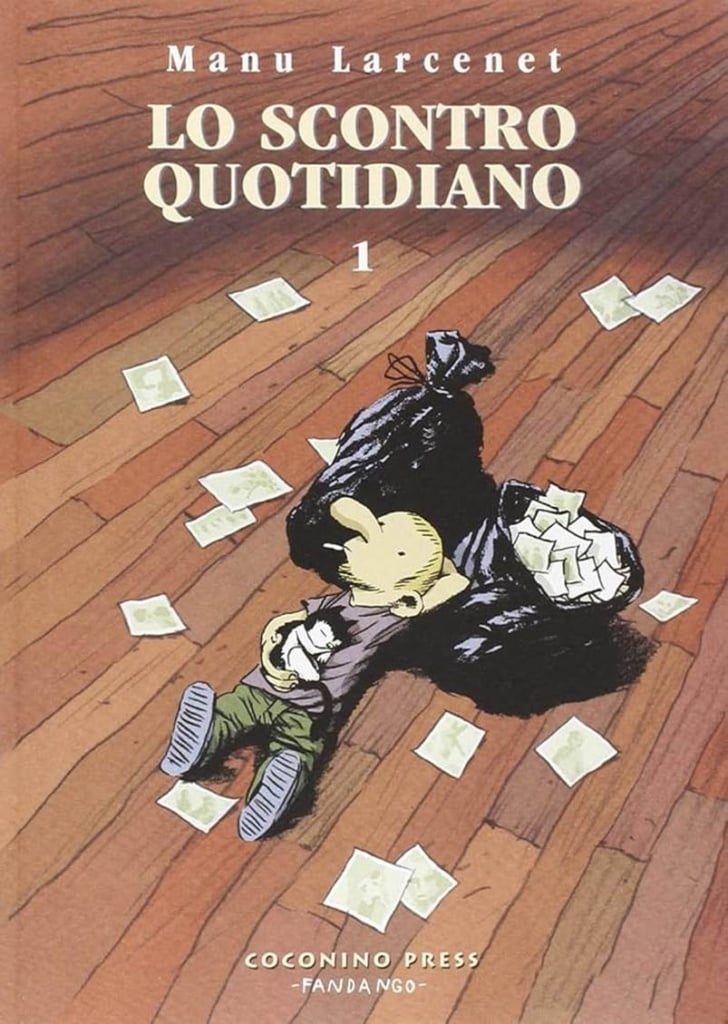

Coconino Press soon established itself as the pre-eminent publisher of graphic novels in Italy, putting out work by the likes of Gipi, Davide Reviati, Francesca Ghermandi, Davide Toffolo and Sergio Ponchione, as well as Italian editions of titles by international icons such as Jiro Taniguchi and Manu Larcenet.

Coconino Press accomplished its mission, successfully showcasing the graphic novel as a serious art form and attracting an older, better-read audience.

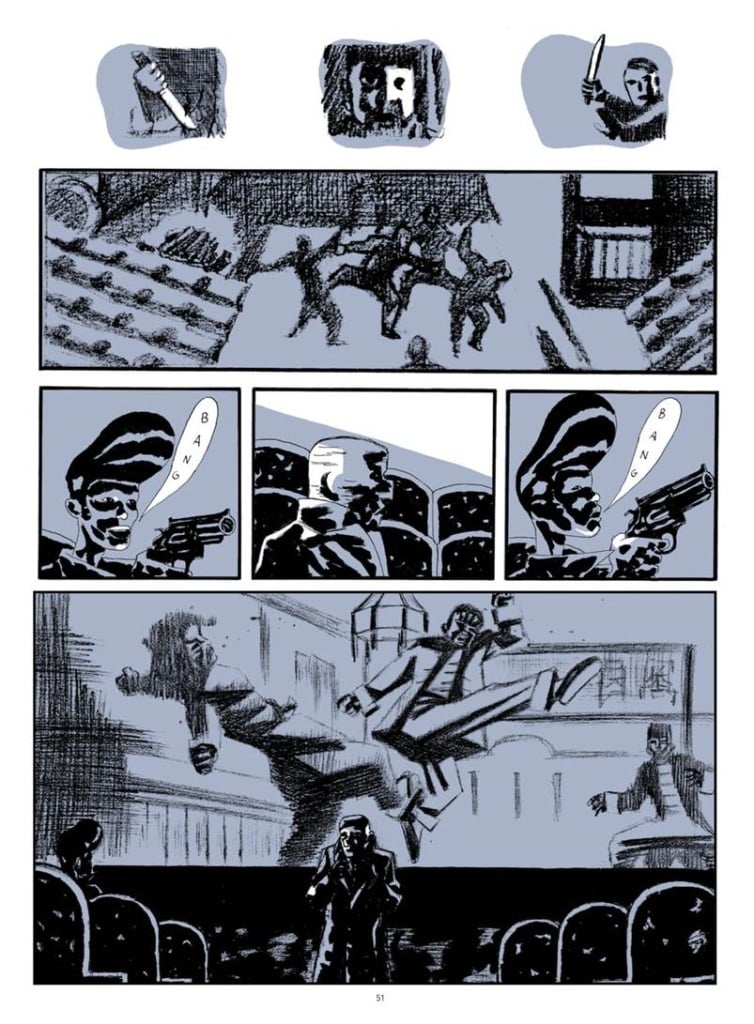

The hit: 5 Is the Perfect Number

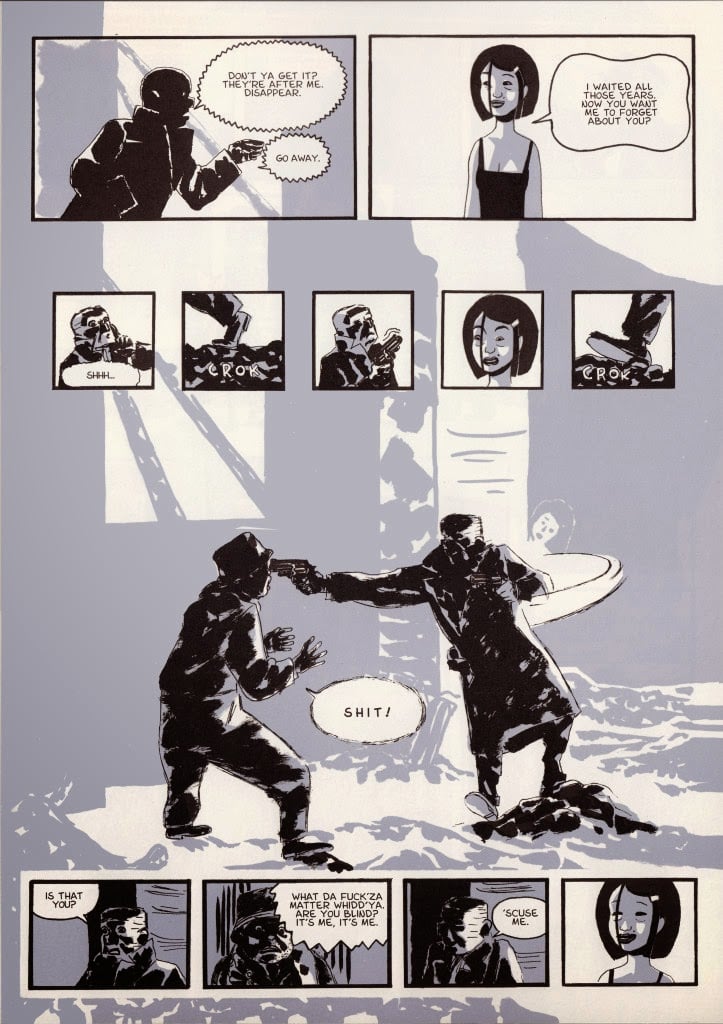

In 2002, Coconino Press published Igort’s best-known and most-acclaimed work: 5 Is the Perfect Number. This noir thriller, which the artist began working on in Japan but only finished on his return to Italy, after almost 10 years of writing and re-writing, marked a turning point in Igort’s career. Set in a rainy, deserted Naples in the seventies, it tells the story of Nino Lo Cicero, a retired contract killer for the Camorra who, after his son’s murder, finds himself sucked back into the underworld in a vortex of violence and vendetta.

5 Is the Perfect Number has an evocative atmosphere, fast-moving plot, psychologically complex characters and a visual style that blends punchy penwork with stark colour contrast. An instant hit, it was soon released in other European markets and won “Book of the Year” at the Frankfurt book fair.

Igort’s most popular book by far, it cemented his reputation as a modern master of comics. Its pulsating plot and evocative setting made it an instant classic – and ripe for big-screen adaptation. This duly came in 2019 with the eponymous film directed by Igort himself and starring Toni Servillo and Valeria Golino.

The Notebooks series: memoir meets graphic journalism

In the years that followed, Igort changed tack again to focus on graphic journalism and memoir. After time spent living in Ukraine, Russia and Siberia, in 2010 he published The Ukrainian Notebooks as part of Mondadori’s Strade Blu series. This drawn reportage tells the stories of the people he met – and their hard scrabble lives – on his travels in the former Soviet Union.

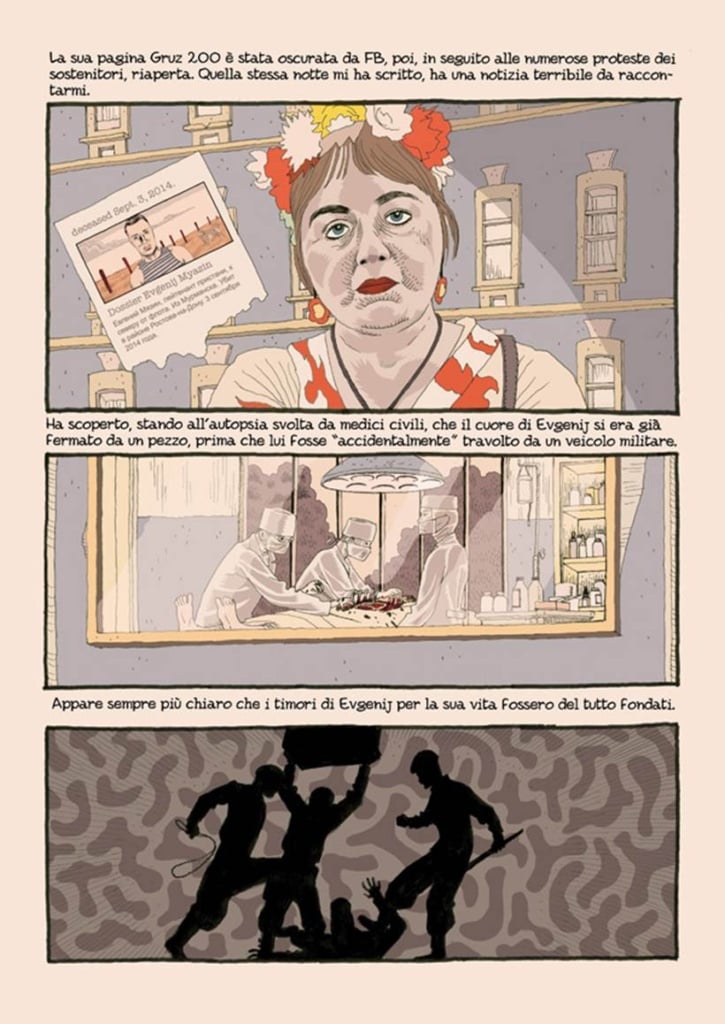

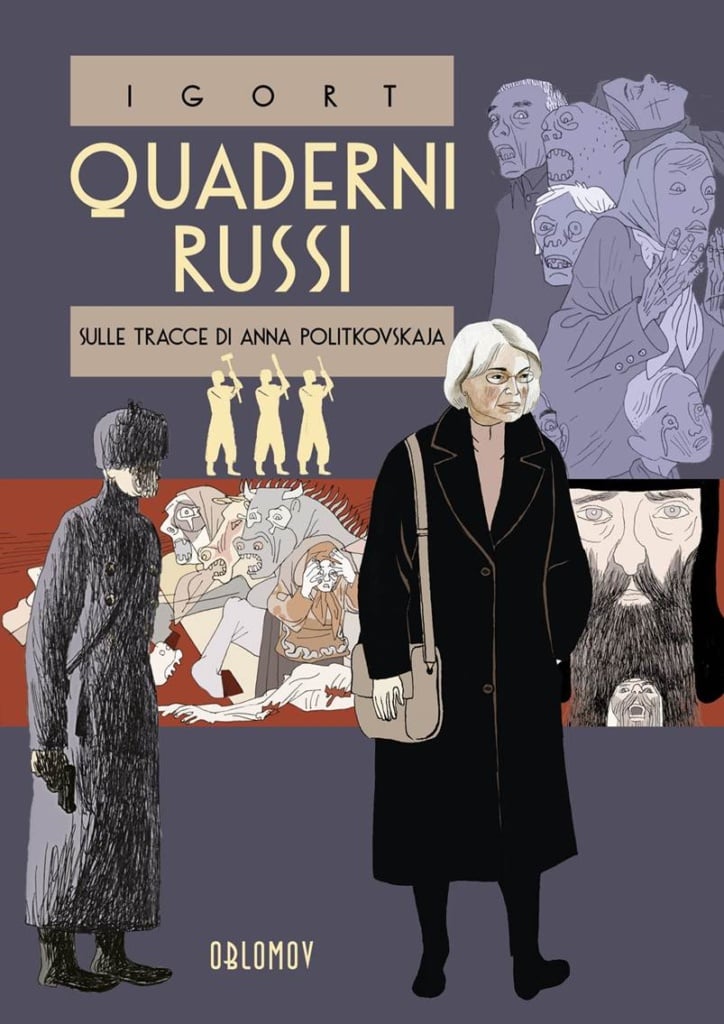

He followed up in 2011 with The Russian Notebooks, an investigation into the death of Russian journalist Anna Stepanovna Politkovskaya, murdered for speaking out about human rights violations and criticising the Russian government. The book shows how the language of comics can be used to talk about serious subjects with empathy and understanding.

In 2014, Igort published an expanded version of The Ukrainian Notebooks with a new subtitle The roots of the conflict, which he followed up in 2022 with the final chapter, Diary of an invasion. For this last instalment, he returned to Ukraine in the days immediately after Russia’s full-scale invasion, where he gathered first-hand accounts on the ground.

In The Japanese Notebooks, released in three volume between 2015 and 2020, Igort explores the nation he fell in love with. Part memoir, part travelogue, part reportage, it recounts the author’s years in Japan, drawing an intimate and insightful picture of the country’s culture. From his workaholic early years in the country to the relationships he forged with successful mangakas such as Tanaka (author of GON), these graphic novels examine Japanese culture through a personal lens – and also introduce readers to manga authors little known in the West.

A critical and popular success, the Notebooks series established Igort as one of the world’s leading exponents of graphic journalism.

Simon & Schuster even published The Ukrainian and Russian Notebooks in America, where they received a favourable write-up in the prestigious New York Review of Books.

Igort’s legacy

Over the course of his career, Igort has picked up countless awards and prizes, which speaks to the artistic merit of his work and its contribution not only to comics art but to culture in general. As the current Editor-in-Chief of both Linus (since 2018) and the latest incarnation of Alterlinus, he continues to champion the language of comics. And with Oblomov, the publishing house he set up in 2016, he continues to experiment and innovate with visual storytelling.

IMAGE-13 – Igort in 2017 (Wikimedia commons)

Igort is still hard at work (he even has a YouTube channel) sharing his deep love and knowledge of comics and sequential art, and continuing to inspire with his groundbreaking creations.