Table of Contents

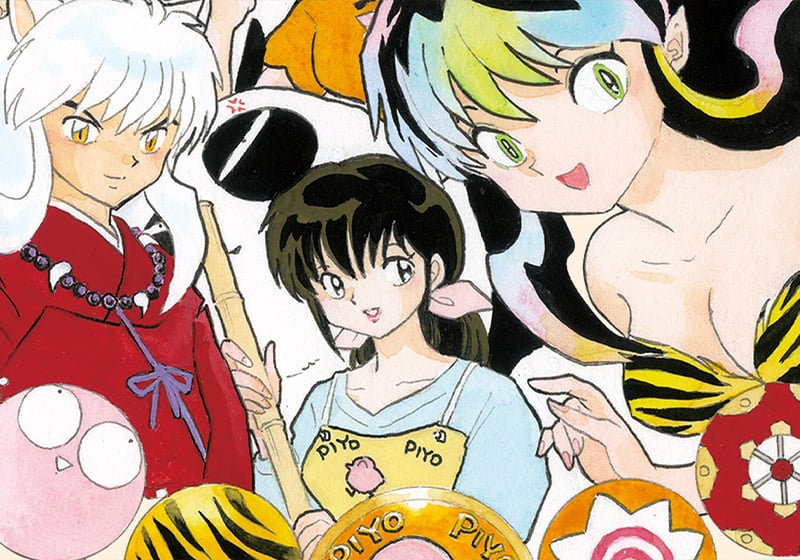

Rumiko Takahashi, born in 1957 in Niigata, Japan, has been nicknamed the queen of manga: a deserved title, given that her creations have sold around 230 million copies worldwide.

However, Takahashi is much more than just a successful cartoonist and mangaka. She is nothing less than a cultural institution, who over the course of an almost 50-year artistic career has created worlds that have captivated millions of readers, from Urusei Yatsura and Maison Ikkoku to Ranma ½ and Inuyasha.

There is a creative paradox inherent in Takahashi’s own story: she has an innate talent for writing shōnen, serialised stories traditionally aimed at boys, but her creations enjoy widespread popularity among both male and female readers.

Over the decades, the author has never lost her creative spark, and today she enjoys virtually global commercial and critical success. She has received the sector’s top awards: in 2018 she was inducted into the Eisner Awards (the equivalent of the Oscars for the world of American comics) Hall of Fame, in 2019 she won the prestigious Grand Prix de la ville d’Angoulême in France, and in 2021 she made it into the Harvey Awards Hall of Fame too.

Childhood, drawing studies and influences

Rumiko Takahashi grew up in a stable family environment. Although she did read shojo (manga for girls) as a child, she much preferred shōnen (manga aimed at boys): Doraemon, Dororo, and Wonder 3 by Osamu Tezuka, not to mention Spider-Man (Ryoichi Ikegami’s Japanese version) and Go Nagai’s Devilman.

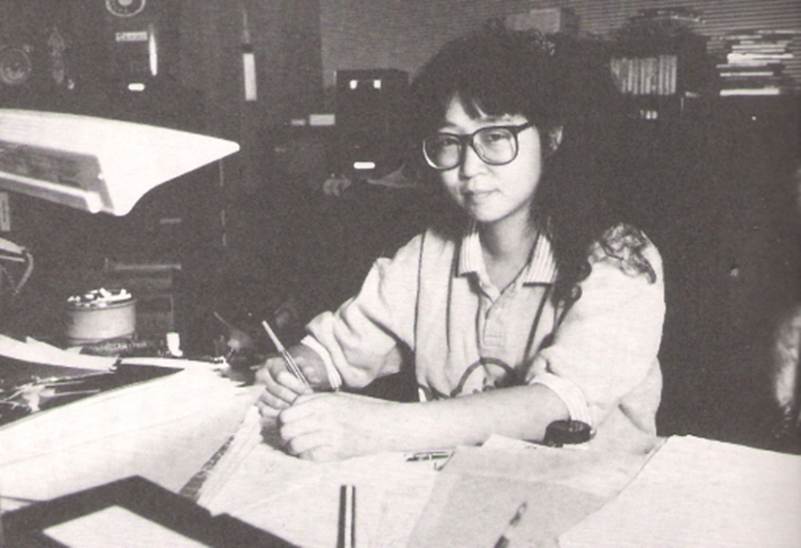

She also read Garo from a young age: an avant-garde magazine written predominantly for an adult male audience (seinen) and featuring comics with much more grown-up stories in the noir, introspective and thriller genres. She took the leap from reader to author at university when she signed up to the Gekiga Sonjuku, a sort of residential training academy, for a six-month course given by the legendary Kazuo Koike, the screenwriter behind Lone Wolf and Cub.

This was a very intense time for the author, as the school expected her to create at least one story a week. Koike taught her a crucial lesson that became the cornerstone of her work: he said the characters always have a central role within a story.

Takahashi’s official debut came with the publication of Katte na Yatsura (literally ‘Selfish People’), a short story that appeared in July 1978 in issue 28 of Shonen Sunday. The work contained, in embryonic form, everything that would follow, and change the author’s life forever.

Lum, the alien who left her mark on a generation

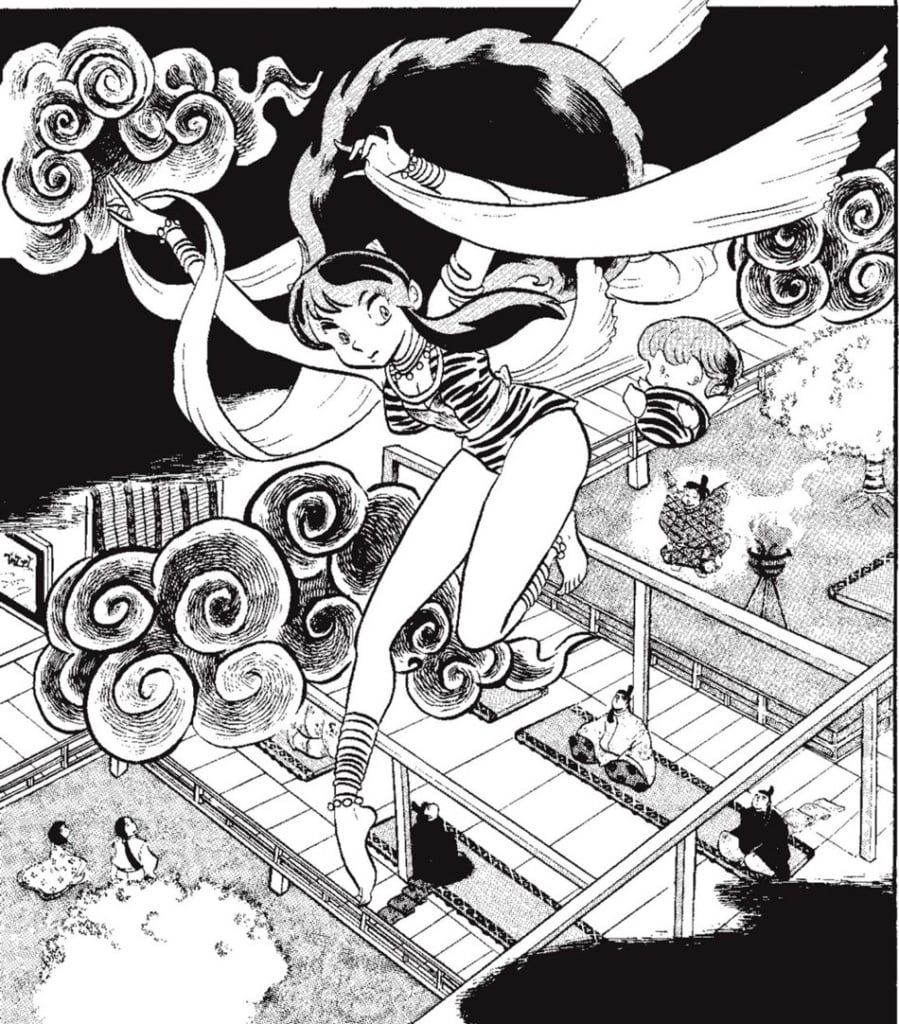

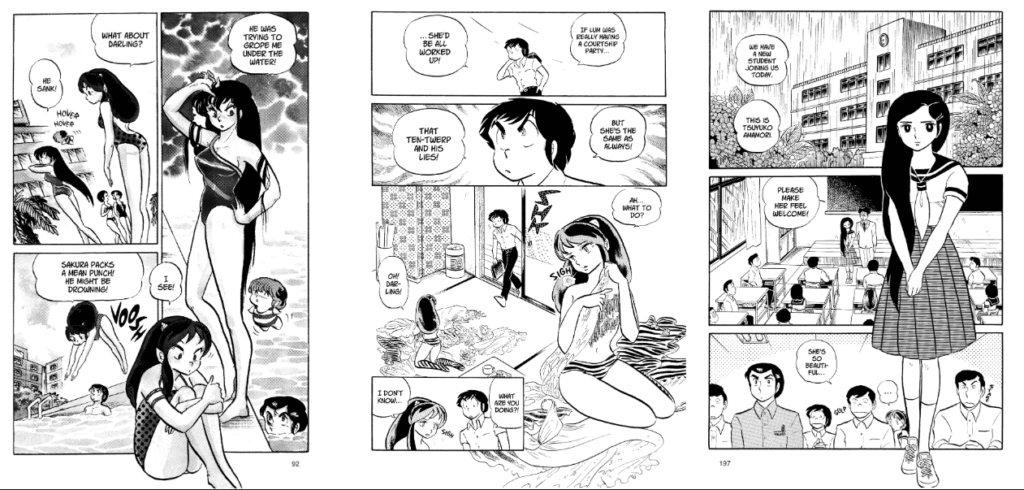

In 1978, the manga series Urusei Yatsura was published in the magazine Weekly Shōnen Sunday, quickly becoming a cultural phenomenon all over the world. It describes the misadventures of the clumsy Ataru Moroboshi, the ‘unluckiest man in the world’.

The plot revolves around a huge misunderstanding, which sees Ataru chosen by the Oni – aliens with divine features – as the husband of the beautiful but highly dangerous alien Lum (inspired by the bikini model Agnes Lum), who can fly and shoot powerful electric shocks at her enemies. Lum agrees to marry Moroboshi, and from then on always refers to him as her ‘darling’.

Urusei Yatsura has an innovative, indeed revolutionary formula: it blends high-school comedy, science fiction and a real, profound love for Japanese folklore and mythology.

The manga features Oni (horned demons like Lum) and Shinto deities that interact with Tomobiki’s high school students in a modern and surreal context. Takahashi also created some genuine archetypes in the work: Lum’s reactions often waver between unconditional love for her ‘darling’ and violent electric shocks to punish his various infidelities. In some ways she plays the part of the tsundere – a girl who hides a gentle heart beneath a fierce exterior, a model that would dominate the world of anime and manga for decades – although Lum tends to be very explicit in her affection for Ataru.

The series was not an instant success; it was initially due to end after five episodes. But the author soon discovered that readers were most interested in the relationship between Lum and Ataru, and so she largely abandoned the sci-fi angle and essentially turned Urusei Yatsura into a romantic comedy.

Takashi’s series really started to take off, and she hired two assistants to help her. She deliberately chose women, believing men would prove too much of a distraction.

As with all of her stories, the driving force behind Urusei Yatsura is its interwoven characters and plots. The manga spawned an anime series (1981–1986) and an incredible six animated films. Its success was cemented in 1981 when it won the Shogakukan prize in both the shojo and shōnen categories: proof of its broad appeal.

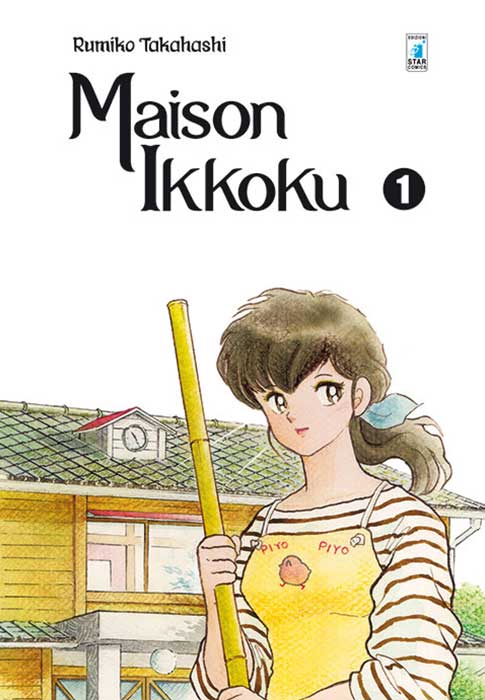

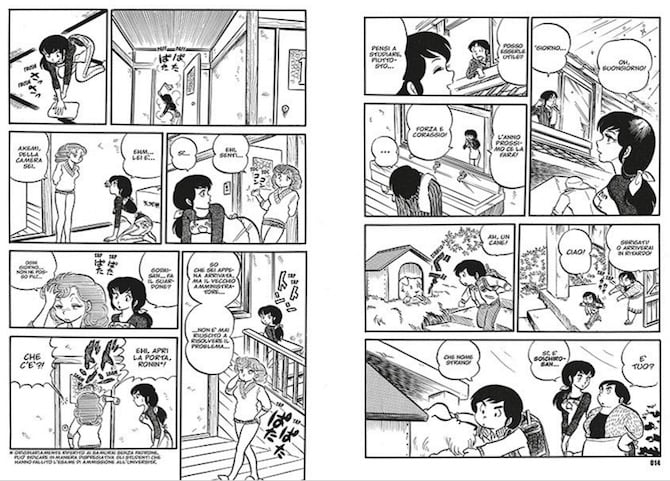

Maison Ikkoku and a ridiculously heavy workload

Following the success of Urusei Yatsura, which was predominantly aimed at teenage readers, Takahashi decided to start work on a new series for slightly older readers. The result was Maison Ikkoku, serialised in 1980 in the magazine Big Comic Spirits.

Featuring abandoned aliens and supernatural powers, Maison Ikkoku is a romantic drama that describes the love story of the penniless and indecisive university student Yusaku Godai and the beautiful Kyoko Otonashi, the young manager of his apartment building. The tone never descends into pure drama; it is – as always with Takahashi – accentuated by jokes and gags that act as the background to the slowly developing love story.

The author introduces a series of bizarre, meddling and disruptive flatmates around the main characters, who act as a catalyst for their relationship. The work is best known for the close attention it pays to the complexity of adult relationships and for its exploration of themes like grief, the difficulty of letting go of the past, and the uncertainty of life.

This period in Takahashi’s career and artistic development helped to reinforce her approach to her craft. First she would talk to the editor at the publishing company (a key figure in the world of Japanese manga). Then, rather than writing a script, she would work out how the story would develop a week at a time, to make it more spontaneous.

The author would then create a draft of the entire story (or at least that particular week’s plot) in pencil, to hone the ‘nah-may’ – the general page layout. Then she would redraw each page again with more detail, and very quickly: completing up to 18 pages in three days. Finally, she would move on to the inking, which she could complete in around two days.

As is common among mangaka, she had an incredibly heavy workload, not helped by the fact that she was working on both Urusei Yatsura and Maison Ikkoku at the same time. Fortunately, she had her two assistants to help her. Takahashi shared her workspace with them – a 15 m² room – and was even forced to sleep in the wardrobe, at least in the early days. Her success eventually allowed her to move to a bigger studio and to hire more assistants, but this story epitomises how extreme rigour and copious amounts of work are commonplace in the Japanese manga world, as authors race to meet its stringent weekly deadlines.

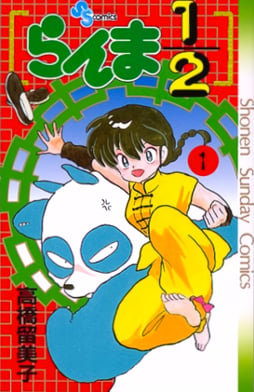

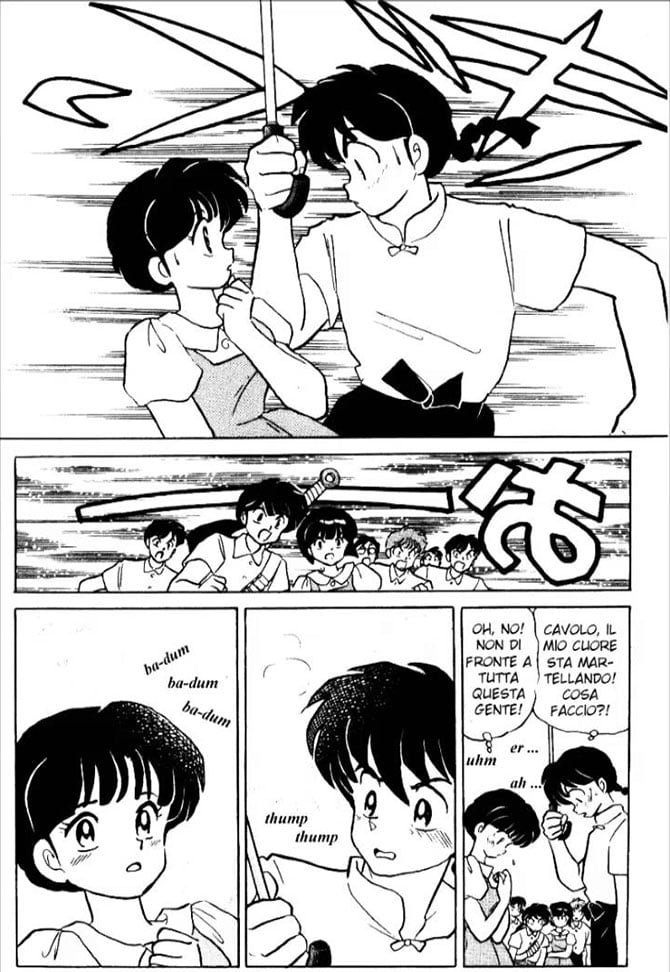

Subsequent works and the success of Ranma ½

1987 marked a major turning point in Takahashi’s career: she decided to wrap up the two series that had made her famous. However, this did not lead to a fall in productivity; quite the opposite, in fact! While continuing to explore the horror genre with Warau Hyōteki (Laughing Target) and Mermaid Saga, Takahashi also launched two new series: the romantic sports comedy One-Pound Gospel and the manga that saw her perfect her formula and that catapulted her towards unprecedented global success: Ranma ½.

This manga series revolves around kung fu, and returns to the absolute chaos of Urusei Yatsura, but this time with an even stronger premise. It features Ranma Saotome, a martial arts expert who, having fallen into a cursed spring in China, turns into a girl every time he is splashed with cold water, while warm water turns him back into a boy. His father, a martial arts teacher, is under the same curse, but in his case water turns him into a panda!

This is not merely a comic device; it is the driving force behind the whole story. Ranma’s dual nature creates heaps of hilarious and embarrassing situations, but also allows the author to explore themes like gender identity, self-acceptance and tolerance.

Ranma ½ was serialised by Weekly Shōnen Sunday between 1987 and 1996, and achieved worldwide success. It was also adapted into two anime series and two animated films.

Takahashi’s later work: Inuyasha

After almost a decade of comedy and forays into the horror genre, Takahashi was ready for another change in direction. In 1996, she immersed herself in a project that would become her second major global success: Inuyasha.

This work, which received the Shogakukan Manga Award in 2002, shifted the author’s focus towards the action fantasy genre, with a broader scope and more drama. She abandoned the episodic structure of her previous works, showing complete mastery of a more horizontal form of storytelling that unfolds as the manga progresses.

The plot follows the fortunes of a young student called Kagome, who falls into a well in a Shinto temple and finds herself in Sengoku-period Japan. There she discovers that she is the reincarnation of a priestess, and joins Inuyasha, a half-demon (or hanyō) on a dangerous mission to recover the fragments of a powerful magical jewel, which is highly sought after by countless demons.

Here too, the main characters inhabit an ‘in-between’ state. Kagome often has to balance her adventures with Inuyasha with her family in the present day, and the half-demon is tormented by his nature, particularly at full moon, when he is robbed of his powers, making him vulnerable and out of control. Only Kagome manages to calm Inuyasha down, helping him understand that his dual nature is actually his greatest strength.

This series offers a perfect blend of all Takahashi’s major elements, and shows the maturity she had developed in her work. The fondness for folklore and bizarre characters seen in Urusei Yatsura, the romantic drama of Maison Ikkoku and the combat of Ranma ½ all converge in the manga, which was also turned into some very successful animated films and an anime.

Rumiko Takahashi’s legacy

It is difficult to quantify Rumiko Takahashi’s importance in the world of manga and global comics in general. Her romantic comedies defined an entire genre, and she also created some of the most successful ever shōnen manga, a traditionally male genre, smashing the barriers imposed by society.

She inspired dozens of authors and a new generation of artists like Hiromu Arakawa (Fullmetal Alchemist) in a field historically dominated by men.

She made good use of the lesson she learned from Kazuo Koike: the characters she created now have iconic status in the imaginations of millions of readers. These figures are never perfect – they are full of doubts and sometimes childish – but they are all very human. Not pure heroes, but complex individuals that are fighting to live in freedom.

Takahashi’s drawing style has never stopped evolving over the decades. Her early works (Urusei Yatsura and Maison Ikkoku) feature rounder faces and softer lines, while with Ranma ½ and Inuyasha her pen strokes became sharper and more dynamic, perfect for the action scenes.

Her legacy therefore not only stems from her exceptional sales figures, but from her ability to create worlds that weave together fantasy and the everyday, laughter and sadness, proving that labels are made to be subverted.