Table of Contents

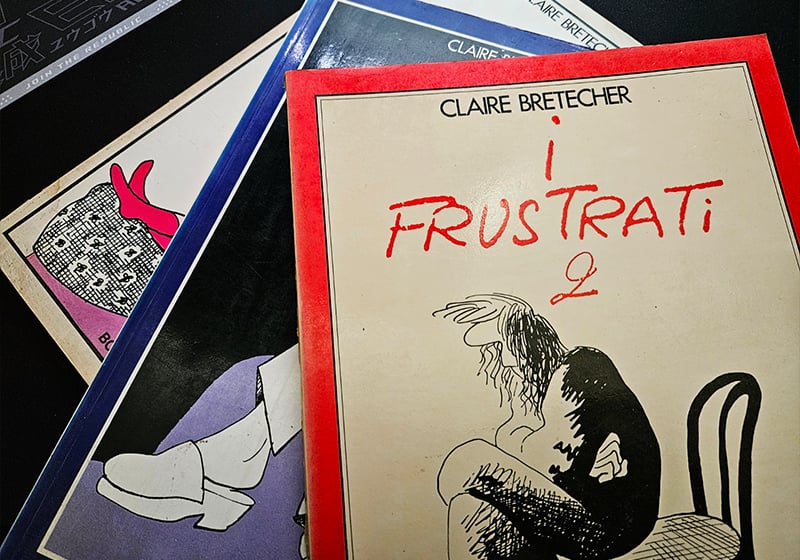

In 1976, the renowned semiotician Roland Barthes called Claire Bretécher the ‘best sociologist of the year’. And he meant it: in just a few quick, almost scribbled lines, along with clever dialogues and satirical undertones, the cartoonist succeeded in capturing the sometimes ridiculous hypocrisy, neuroses and worries of the intellectual middle classes in post-1968 France.

She overturned all the standard conventions of bande dessinée, a genre that had long been dominated by men. And she is considered, alongside Marcel Gotlib and Nikita Mandryka, one of the key figures who moved French comics into exploring more grown-up themes, with her ruthlessly insightful stories.

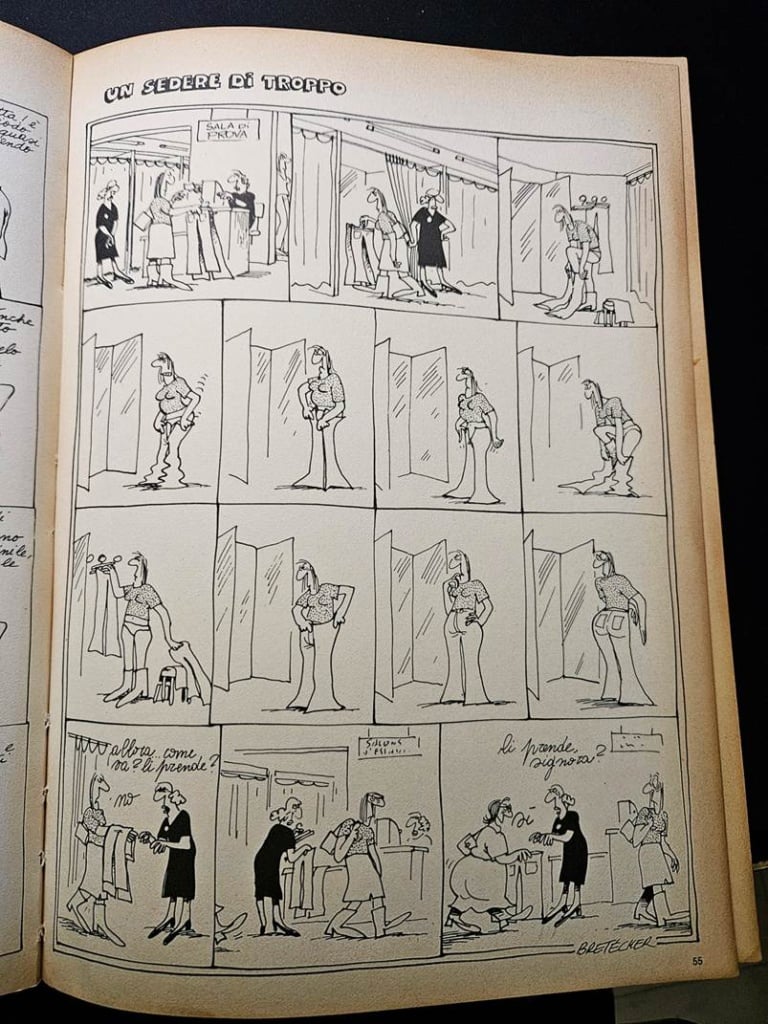

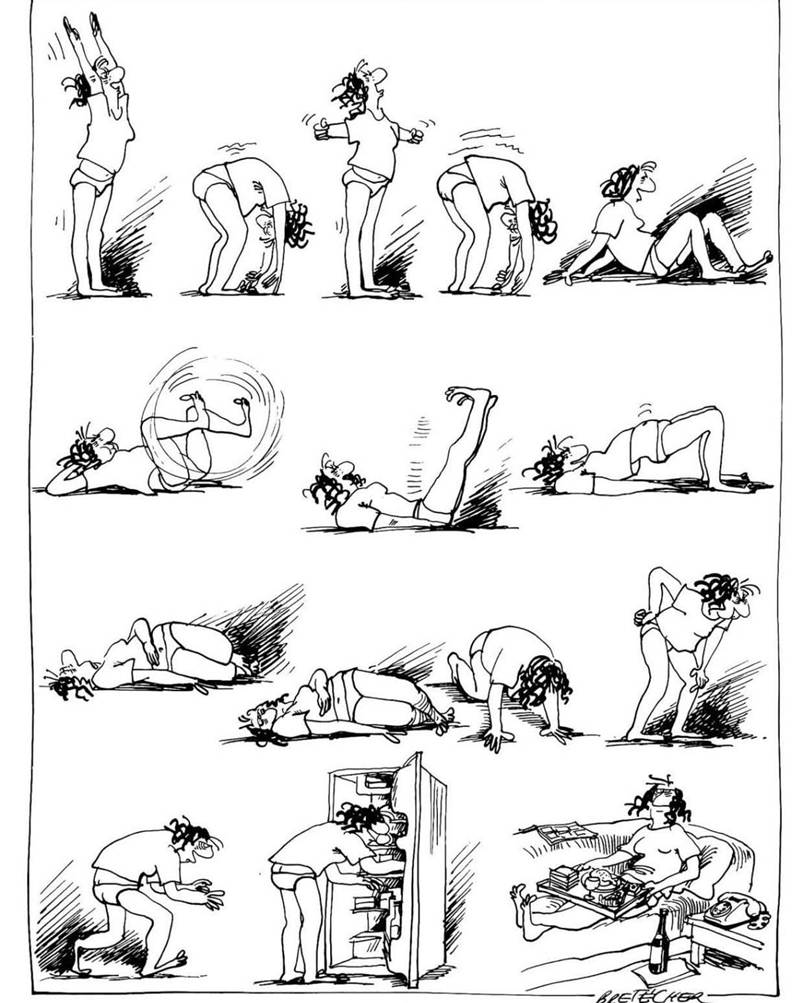

She left behind the classical virtuosity of the Franco-belgian ligne claire, and instead introduced a style based on gestures, comic timing and the posture of her imperfect characters.

In comics like Cellulite, Les Frustrés and the analysis of teenagerdom Agrippine, she used humour to introduce topics that were barely ever seen in print at the time, like sex, politics, motherhood and psychoanalysis.

Childhood, influences and first publications

Claire Bretécher was born in Nantes in 1940 and grew up in a middle-class Catholic family. Her father was a lawyer and her mother was a housewife, and her childhood was traditional and rather austere. Her father was a violent man, while her mother pushed her to become as independent as possible, an upbringing that in time would provide a wealth of material for her stories.

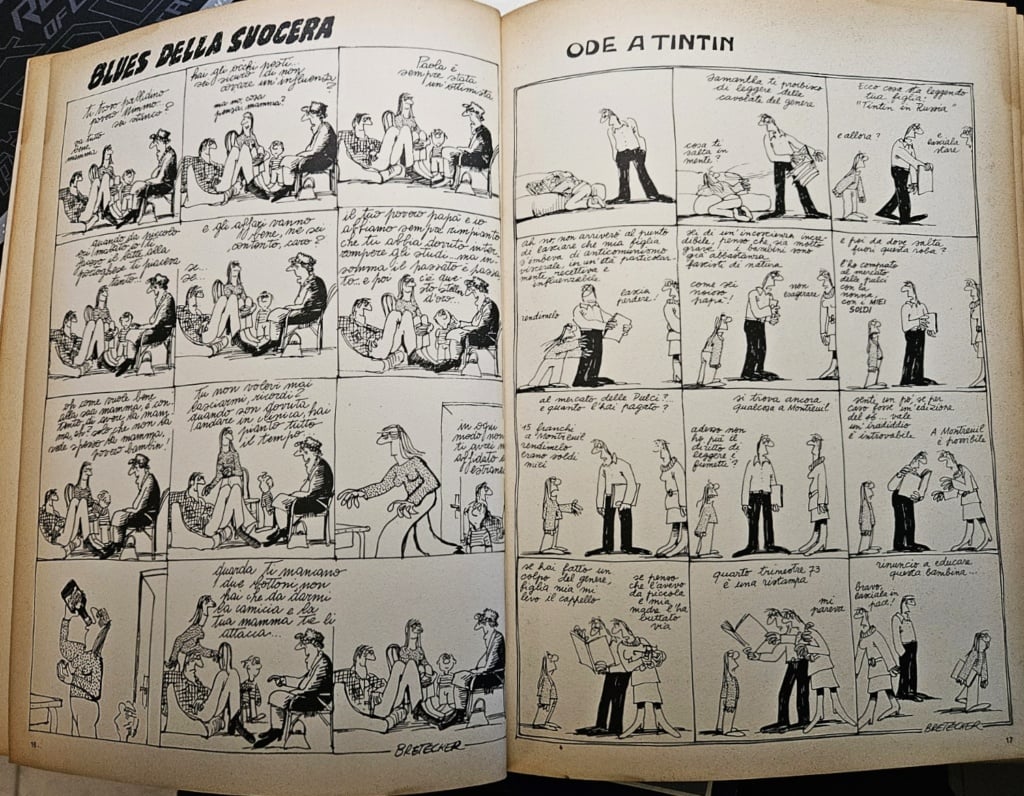

Her early comics influences came from two Franco-Belgian classics: Hergé‘s Tintin, and Spirou. She started drawing comics as a child, although she often abandoned them as they were considered an inferior art form. She attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Nantes, then moved to Paris in the early 1960s.

Her first few years in the French capital were tough: she worked as a babysitter and a drawing teacher in schools, but she really wanted to work for newspapers. Her first drawing was published in Le Pèlerin magazine and she later worked with Bayard Presse on their children’s magazines.

She carried on drawing, developing her style and trying to get a foothold in the almost impenetrable world of the major weekly papers. Her first big break came through a collaboration with René Goscinny, the co-creator of Asterix, on the comic newspaper L’Os à Moelle. She did the drawings and Goscinny wrote the story for Facteur Rhésus, a humorous strip starring a postman.

Publications in magazines: Spirou and Pilote

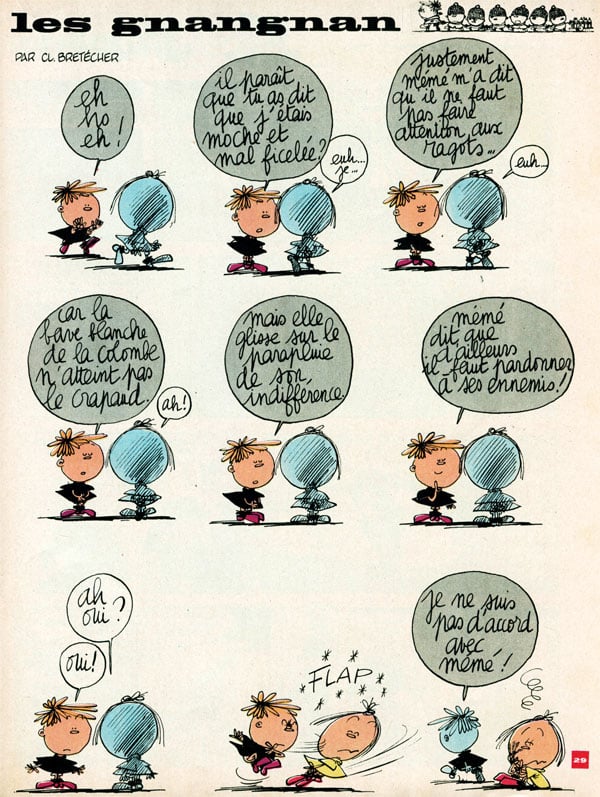

A major turning point came in 1967, when the artist joined the team of illustrators at Spirou magazine and created a story starring a small gang of children, Les Gnangnan, inspired by Charles M. Schulz‘s Peanuts.

After working with Tintin magazine and on other projects like the strip Les Naufragés, which stood out for its cynical humour, the artist was hired by Pilote magazine, where she started publishing much more adult comics.

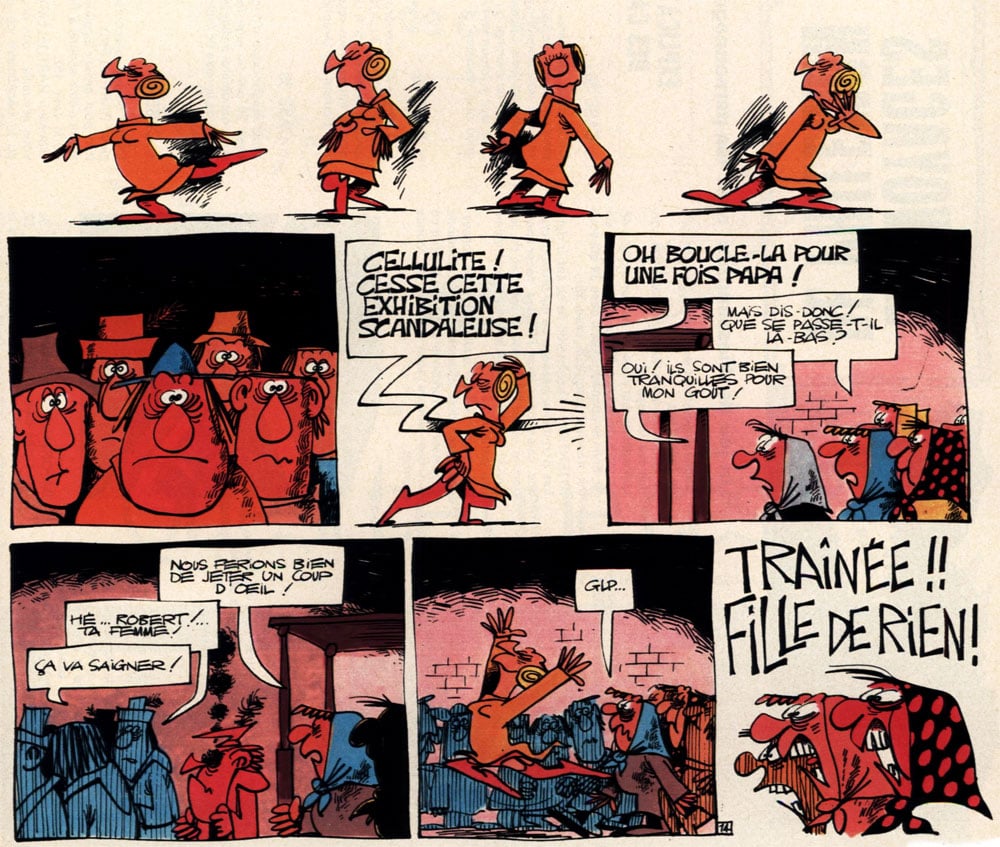

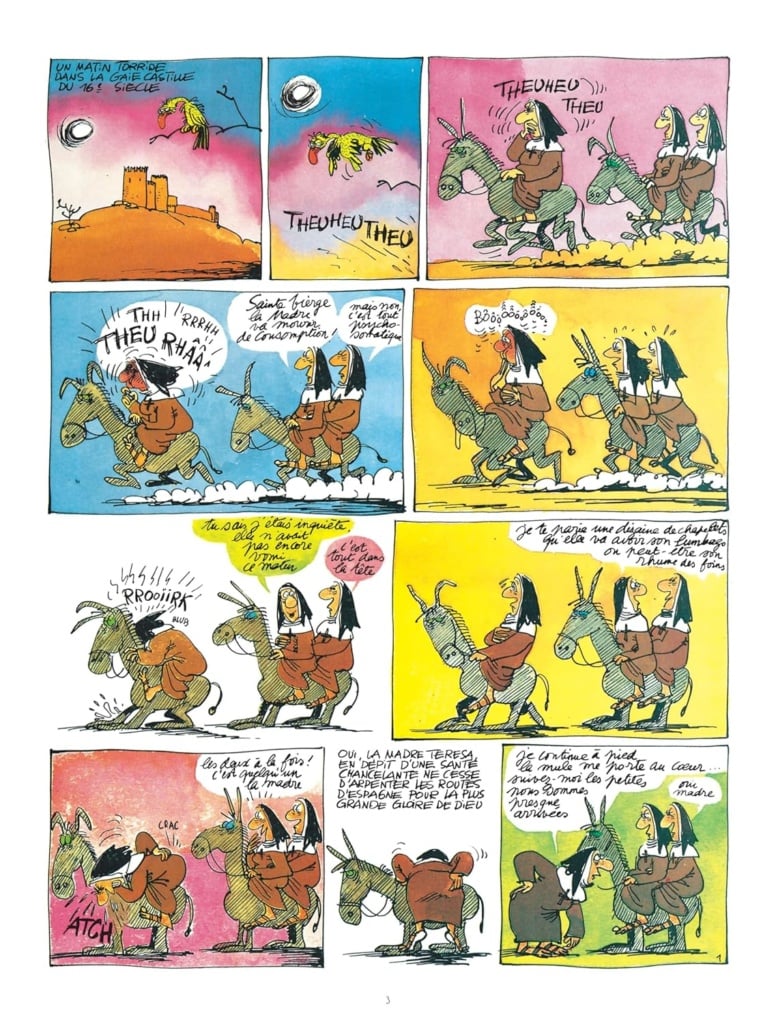

Her first creation was Cellulite, a series published from 1969 to 1977 and set in medieval times. This was a period where comics tended to be dominated by seductive, flawless heroines like Barbarella; Bretécher introduced a character who was the polar opposite named Cellulite, who became the first anti-hero in Franco-Belgian comics. Cellulite is an ungainly and complex young woman, who is not beautiful in the traditional sense and lives in a farcical medieval world. She is tired of waiting for her Prince Charming to come along, and so takes the initiative and sets out to find him… and invariably fails.

In Cellulite, the artist upends the traditional fairy tale; her lead character does not want to be defined by male approval. While the series is funny, some of the humour is dark and even cruel.

Bretécher continued her career at Pilote, but towards the end of the 1960s she was increasingly driven to focus on more adult topics – politics, sex and society – in her comics, themes incompatible with Goscinny’s editorial line.

The launch of L’Écho des Savanes and the left-leaning press

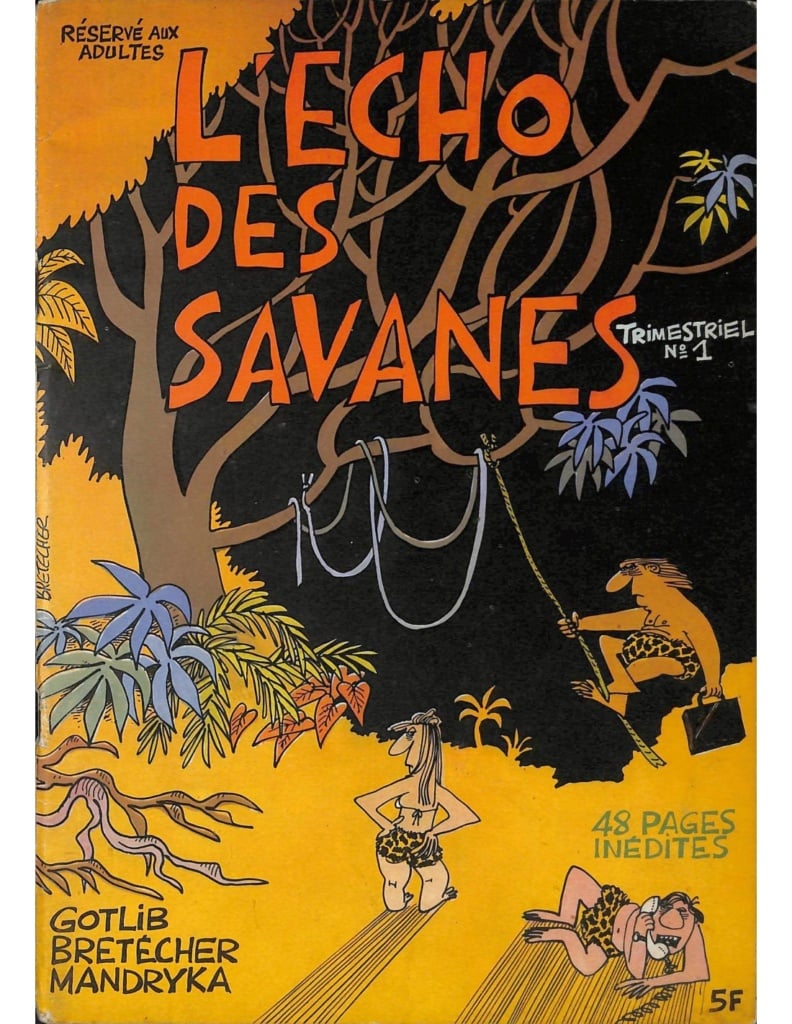

In the early 1970s, some of Pilote‘s artists started to turn against Goscinny’s editorial approach. Although they continued to work at Pilote until 1977, Claire Bretécher and her colleagues and friends Marcel Gotlib and Nikita Mandryk also created their own independent magazine called L’Écho des Savanes.

The magazine’s title, which translates as ‘The Echo of the Savannah’, poked fun at colonial and adventure magazines. Its creators took charge of everything, including production, printing and distribution, following in the footsteps of a long list of self-produced magazines from the era, including Fluide Glacial, Métal Hurlant and Psikopat, which sought greater artistic freedom than that offered by established publications’ more conservative editorial lines.

Employing psychedelic graphics and surreal humour, in L’Écho the artist examined themes like relationship dynamics, abortion and contraception. However, Bretécher was more of a sociologist than an anarchist, and wanted to remain independent: her aim was to appear in the national, generalist press and so be read by thousands of people.

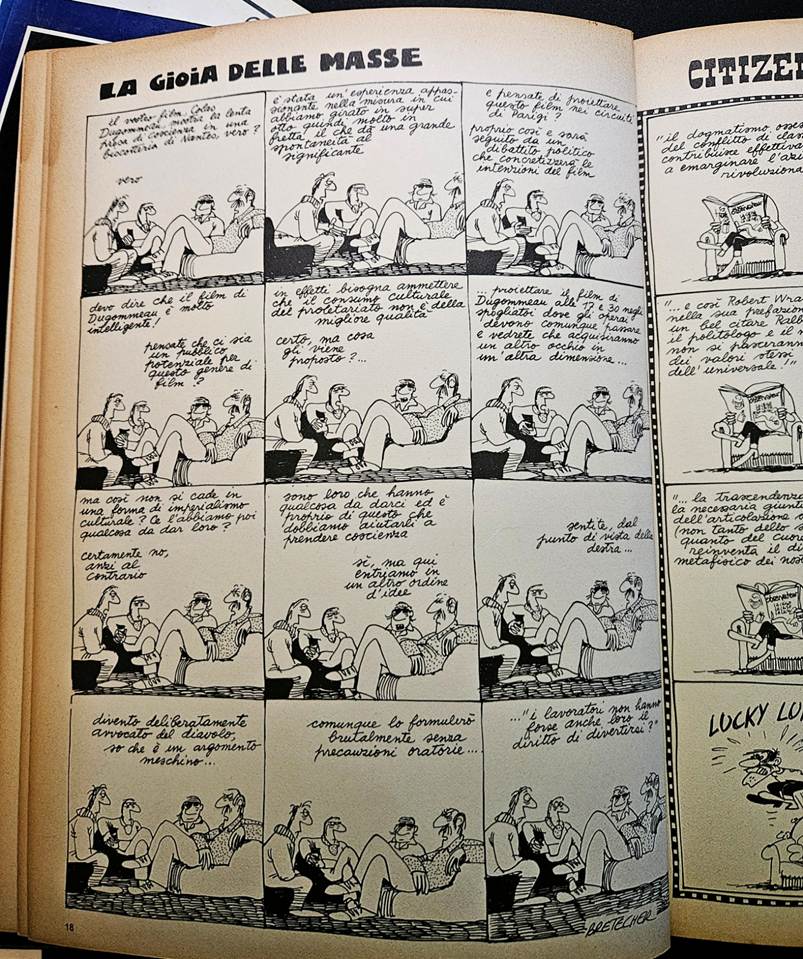

After some time at the magazine Le Sauvage in 1973, she made her debut in the society section of the left-leaning magazine Le Nouvel Observateur, publishing Les Frustrés (‘The Frustrated’) from 1973 to 1981. This comic used subtle yet painful irony to lay bare the hypocrisy and pointless neuroses of the wealthy men and women of the French bourgeoisie.

Les Frustrés: Claire Bretécher’s masterpiece

Les Frustrés made its debut in Le Nouvel Observateur on 15 October 1973. It appeared weekly, and featured self-contained stories with no recurring characters.

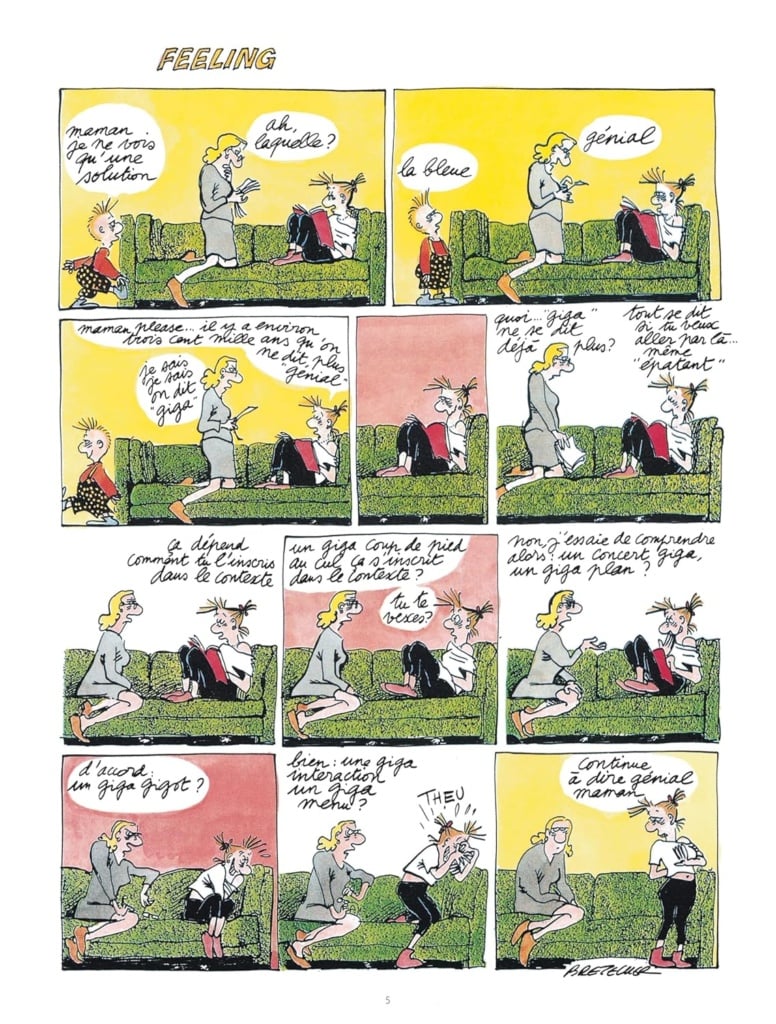

Instead, the artist created a series of archetypal characters: mothers, housewives, career women, feminists, students, and so on, with all their everyday problems, everything from loneliness and anxiety to total despair. The ‘frustrated’ people referred to in the title were the Parisian bourgeoisie, progressives and intellectuals who had taken part in the protests of May 1968 (or claimed to have done) but were now struggling to come to terms with the contradictions of their daily lives. They were frustrated with politics, sex, their partners, their children (raised with “modern” educational principles that had turned out to be disastrous) and particularly with themselves.

Although men are present in these stories, they are often portrayed as supporting characters. The rest of the characters are almost always stationary: sat on a sofa, or stuck in a boring dinner, anxious and displaying nervous tics.

Bretécher uses a simple and minimalist style and pen stroke in her cartoons. The pages mostly have a white or dark background with walls, tables and sofas the only recurring elements; dialogue takes centre stage. Her pen strokes are fast, nervous, almost rude, but ideally suited to narrating the witty, sad, provocative and sometimes embarrassing episodes and anecdotes. Each pages contains the same number of panels, which tend to be square.

The few lines in these drawings perfectly encapsulate the rude snobbery and decadence of a part of society, holding a mirror up to the behaviour of the French intelligentsia.

Les Frustrés was a great success, pushing the boundaries of comics and becoming a cultural fixture: it was adapted for the stage, made into cartoons and translated into various languages.

Later works: from Les Mères to Agrippine

The artist got married in 1977, but the couple did not have children. In 1980 she produced a controversial biography of St. Teresa of Avila, La Vie Passionnée de Thérèse d’Avila, which was heavily criticised by Catholic readers: the artist dared to insinuate that the saint’s religious ecstasy may have been due to epileptic fits.

In 1982 she published Les Mères (‘Mothers’), a volume dedicated entirely to the topic of motherhood. The original text suggested that her choice of this theme may have been influenced by the lack of children from her marriage at the time. The following year, however, she met a new partner and had a child, and published Le Destin de Monique, dedicated to pregnant women, in 1984.

From 1988 onwards, Claire Bretécher focused most of her attention on Agrippine, a series exploring the world of young teenagers. It tells the story of a normal middle-class girl from Paris and all her futile existential problems caused by school, love and friendships.

Many people have associated Claire Bretécher’s work with the feminist movement, but the artist never called herself a feminist. She often embraced progressive battles in support of women and against all forms of racism, but never openly declared herself part of a specific group.

Although she worked in a male-dominated environment, she always said that she never suffered any misogyny or harassment of any kind in the workplace.

Claire Bretécher’s legacy

Claire Bretécher died in 2020, leaving behind her a legacy that extends far beyond the comics world. She showed that comics can be just as powerful a social analysis tool as an essay or film.

Her approach to drawing became almost the go-to style for those who simply want to communicate, freeing French comics from the pursuit of technical virtuosity for its own sake. She was a true pioneer as a woman in a male-dominated world, using humour as a scalpel to reveal the hypocrisies of a slice of society.

A panel by Claire Bretécher. – © Dargaud – https://www.facebook.com/YogaKamalaAudrey/posts/en-ce-1er-avril-le-yoga-vu-par-claire-bretecher/1162617265656756/

She helped pave the way for other female artists, and her works had a huge cultural impact, elevating comics to something used for social criticism, but with tongue always slightly in cheek.