Table of Contents

Georges Prosper Remi, better known as Hergé, was born on 22 May 1907 in Etterbeek, Belgium. A towering figure in the comics world, he created one of the bestselling and best-loved comics series of all time, The Adventures of Tintin, as well as other popular works such as Quick & Flupke and The Adventures of Jo, Zette and Jocko.

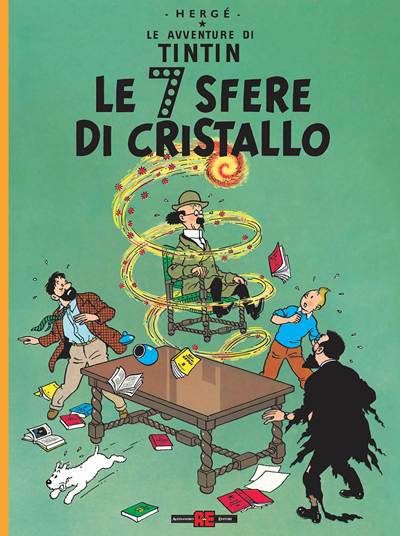

Hergé’s comics have entertained millions over the years. Since the 1930s, kids around the world have grown up in the company of iconic characters like Tintin, Captain Haddock and Professor Cuthbert Calculus.

The Belgian’s creations have escaped the pages of comics albums and jumped onto our screens in films, TV series and videogames. Along the way, Hergé’s works have inspired other creatives, from artists and illustrators to screenwriters and designers.

Childhood, early influences and discovery of drawing

Like many artists, Remi showed a keen interest in drawing from a young age, filling his school exercise books with sketches and illustrations. On leaving school, he enrolled in an art course at the Institut Saint-Luc in Brussels, but dropped out after a year: he hated other people telling him what to draw. This meant that Remi was largely self-taught: he developed his drawing skills by simply studying the work of other artists.

Among his greatest influences were the illustrator René Vincent and classical painters like Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel and Johannes Vermeer. But Remi also admired the work of contemporaries such as Joan Miró, Lucio Fontana and Serge Poliakoff.

In the comics world, his heroes were George McManus, Émile-Joseph Pinchon (whose Bécassine character inspired the face of Tintin), Winsor McCay, Rube Goldberg and, most of all, Alain Saint-Ogan: it is the latter’s influence that most clearly shines through in Hergé’s work. Later in his career, he also rated Moebius, Robert Crumb, Hugo Pratt, Claire Bretécher and Milo Manara.

The adventure novels of Alexandre Dumas were a fertile source of inspiration, as were the films of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. These slapstick masters taught Hergé how to construct a joke, while other films schooled him in the art of montage, the building of suspense and the creation of dynamic movement.

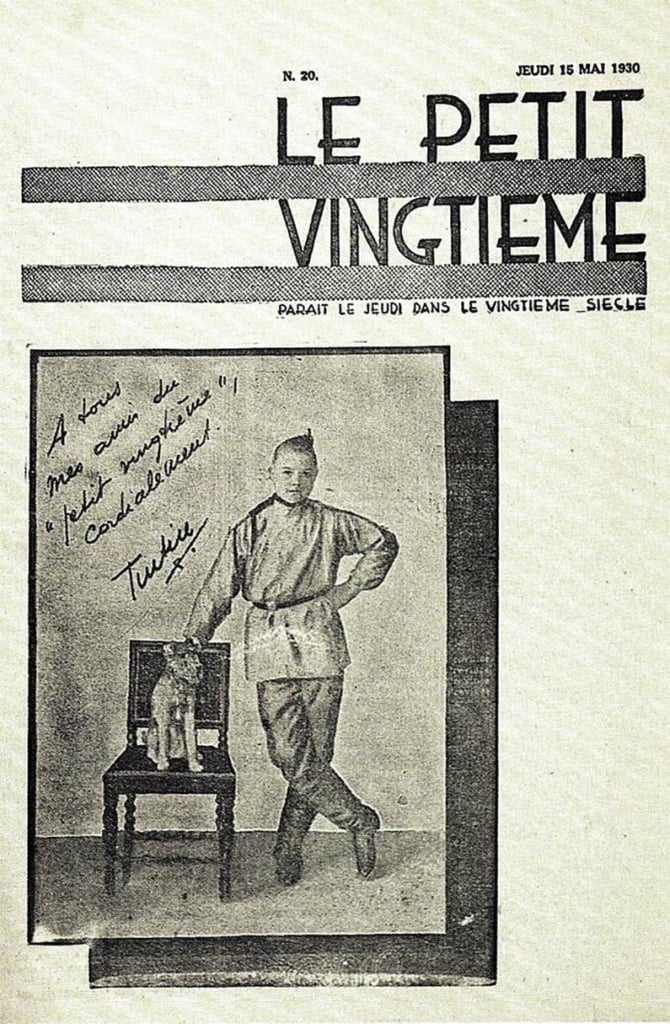

The young Rémi was a member of a Scout troop, and scouting was one of the few bright spots in an otherwise unhappy childhood: “I felt mediocre and saw my youth as something grey”, he told the makers of a documentary about him. It was Baden-Powell’s movement that gave Rémi his break as a cartoonist. His debut was published in the magazine Le Boy-Scout Belge, signed with his initials “R.G.“. These later morphed into his pseudonym Hergé, which is pronounced the same way as “R.G.” in French.

Published between 1926 and 1929, this first comic strip was called The Adventures of Totor and followed the capers of the titular Totor, a boy scout in America. It was a text comic, with speech presented in captions below the images, as was common practice at the time.

Hergé’s style and the birth of ligne claire

From the outset, Hergé had an immediately recognisable style, which he developed in response to the limitations of printing technology at the time. In the 1920s, ink tended to run when newspapers were printed,

so to minimise smudging, Hergé drew with thin, clear and clean lines, without hatching or superfluous detail. He enclosed each panel in a black border and separated it from the next with white space.

At first, Hergé worked in black and white only, before embracing bold colours from the 1940s onwards. Initially known as ‘Brussels School’, it was later rebaptised ligne claire in the 1970s by Dutch cartoonist Joost Swarte.

Ligne claire is now synonymous with Franco-Belgian comics, but over the years countless cartoonists from around the world have imitated or developed the style in their own work.

Early works and the birth of Tintin

In 1925, Hergé joined Le Vingtième Siècle, a Catholic newspaper edited by priest and journalist Norbert Wallez. He spent a couple of years doing military service, before returning to the paper as a reporter and photographer. It was here that he met Germaine Kieckens, the woman who would become his first wife.

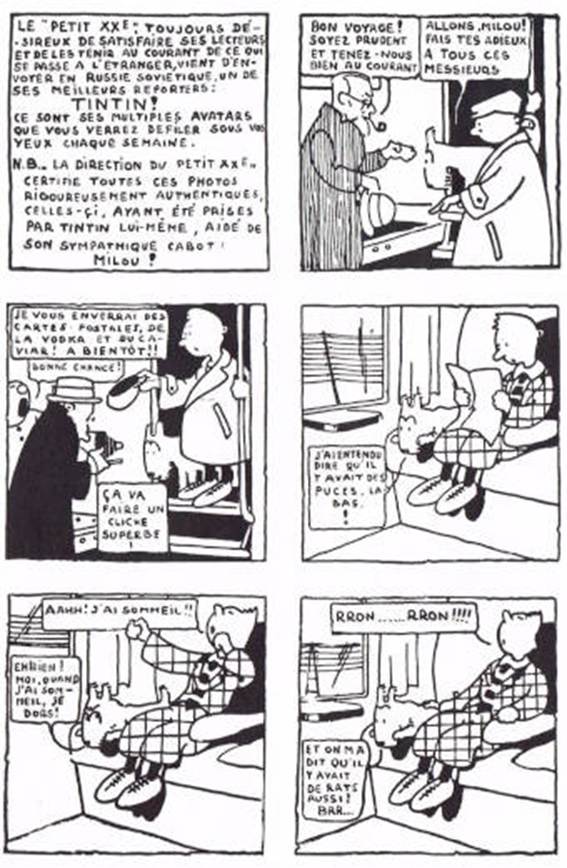

His big break came in 1928, when he was asked to create a weekly children’s supplement, which would be called Le Petit Vingtième. With drawings accompanied by captions, the first simple stories were like cinema on paper.

Around this time, Hergé noticed that cartoons in American newspapers were using speech bubbles for dialogue rather than captions, so he began doing the same. His first comic with speech bubbles was The Adventures of Tintin, which appeared in Le Petit Vingtième from 1929 to 1930 on a commission from Wallez.

An ultra-conservative Catholic, Wallez wanted to create a comic that warned young people of the dangers of communism. The Tintin character is a young reporter who, together with his inseparable dog Snowy, travels the world in search of stories and adventures.

On their first outing, in Tintin in the Land of the Soviets, the pair head to Soviet Russia. From the start, Tintin is presented as a journalist, although he acts more like a detective, given that he investigates and has criminals arrested.

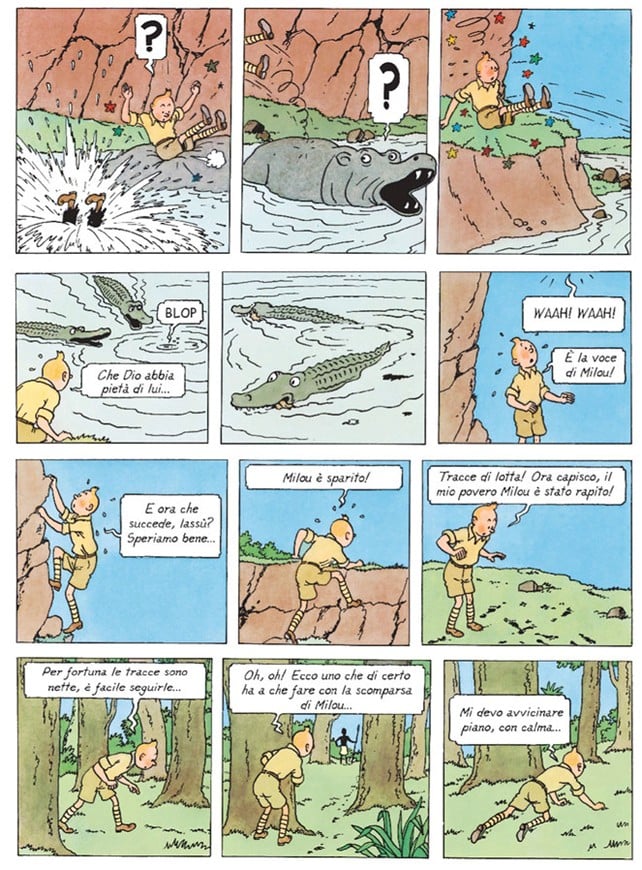

Despite this and subsequent adventures being propaganda pieces with rather rudimentary plots, the series was an instant success. The second instalment was Tintin in the Congo (1930-1931), which praised colonialism and the work missionaries were doing to ‘educate’ the local population. In the next story, Tintin in America (1931-32), Tintin and Snowy land in the USA, where Hergé had great fun in pitting his hero against Al Capone and Native Americans.

These early stories were heavily influenced by Wallez, but Hergé soon began to stamp his own personality on the series.

From propaganda to masterpiece

The first Tintin stories have undoubted historic value, but are not his best, not least because they contain various offensive stereotypes. However, some contextualisation is needed: at the time, Hergé was a young man influenced by the prejudices of the era and did not take his work too seriously. It was only after Wallez’s sacking in 1933 that Tintin’s creator won greater creative freedom and dialled down the propaganda. Later in life, he would frequently apologise for the content of his early work.

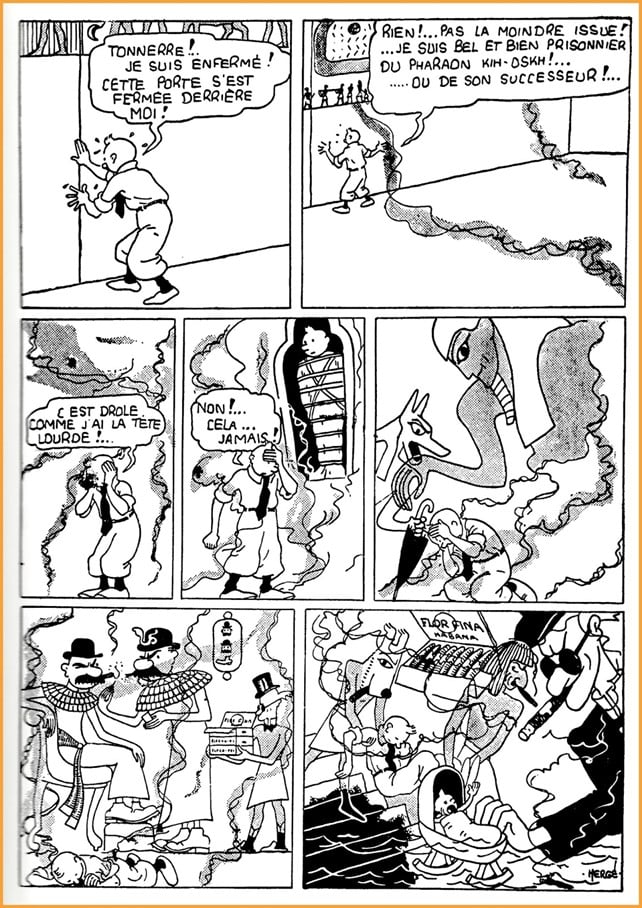

The fourth Tintin tale was The Cigars of the Pharaoh. Published from 1932 to 1934, it tackles more mature themes and introduces characters like the hapless Thomson and Thompson and archenemy Roberto Rastapopoulos.

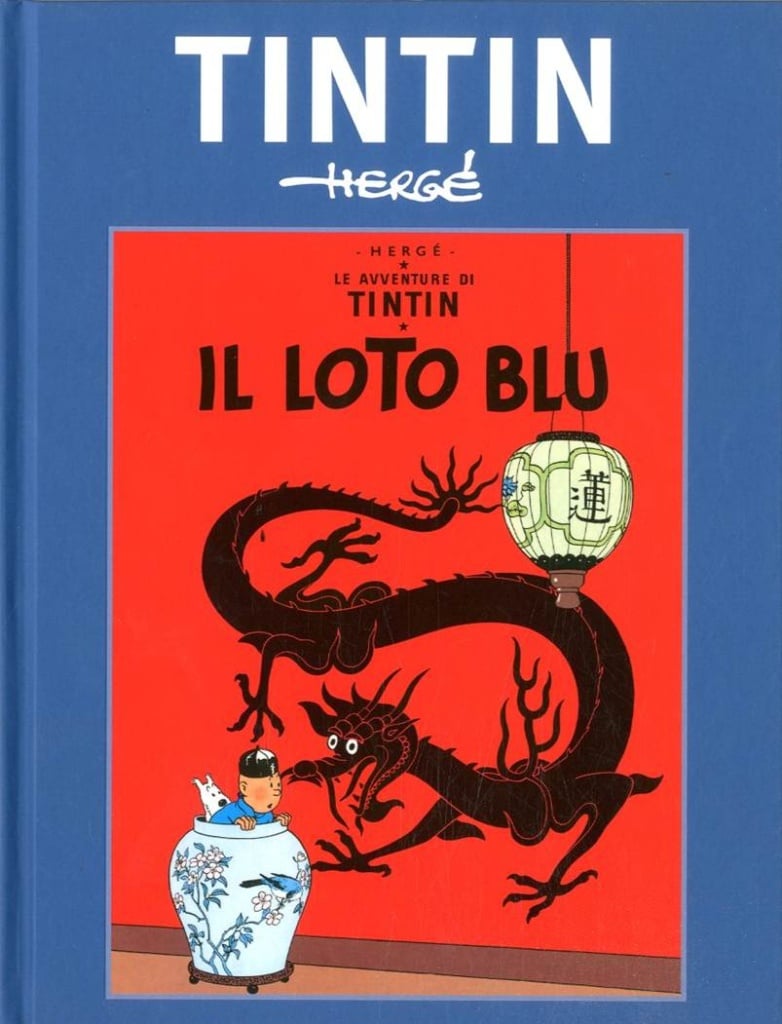

With The Blue Lotus, published from 1934 to 1935, Hergé showed greater care and historical detail in depicting China. His drawing and storytelling are better, too, and he even introduced an element of political satire. The Blue Lotus is widely regarded as a masterpiece, and was ranked in 18th place on Le Monde’s 100 Books of the 20th Century.

This book literally changed the way that Hergé worked: previously, he would think nothing of making last minute changes before sending his panels to press, but this time he took a much more studied and serious approach. Before constructing each story, he spoke to experts, looked at photographs, visited museums and read specialist literature. And he became meticulous in his penwork, which was as technically accomplished as it had ever been.

The Blue Lotus and later Tintin adventures cemented Hergé’s place in the pantheon of great European comics artists. In all, he created 24 Tintin stories, the last of which, Tintin and Alph-Art, remained incomplete upon his death but was published posthumously in sketch form.

Hergé’s other notable works

As the chief artist for Le Petit Vingtième, Hergé created a slew of other comics series. Among the most popular was Quick and Flupke, serialised between 1930 and 1941, which told of the shenanigans of two mischievous little rascals. With this comic strip, the author delighted in making surreal gags and breaking the fourth wall as he found greater freedom to express himself than that afforded by the first Tintin stories.

Comics for other publications included Mr. Bellum (1939), as satirical cartoon strip about Hitler and Mussolini.

Between 1936 and 1939, Hergé published Jo, Zette and Jocko in Catholic magazine Coeurs Vaillants. The comic follows a boy named Jo, his sister Zette and their pet monkey Jocko as they get up to capers in the vein of Tintin. Despite being a success, the artist never truly warmed to the series because of the creative constraints imposed by the publishers.

Studio Hergé and international acclaim

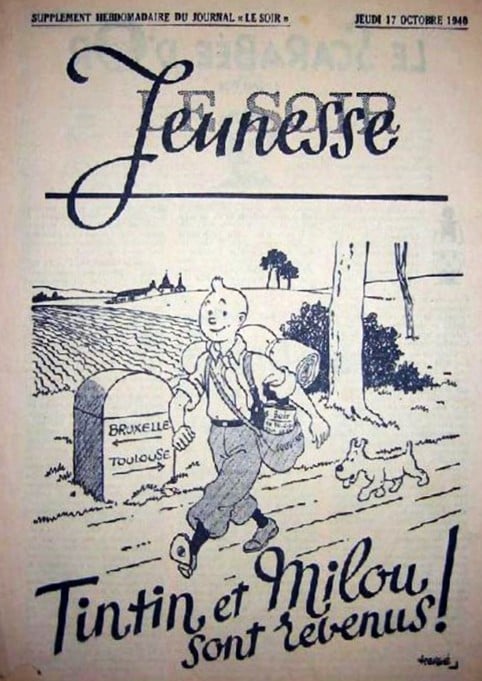

The Nazi invasion of Belgium in 1940 forced the closure Le Vingtième Siècle and with it Le Petit Vingtième supplement. Hergé, who was halfway through writing The Land of Black Gold at the time, found a new role at another children’s supplement, Le Soir-Jeunesse, where he continued to bring readers the adventures of Tintin.

Some of the most popular Tintin stories were published during this period, such as The Crab with the Golden Claws (1940-1941), which introduced readers to Captain Haddock, and The Shooting Star (1941-1942), which explored the anxiety of war.

After the liberation of Brussels in 1944, Hergé found himself unable to ply his trade once more: along with the entire editorial staff, the author was arrested on charges of collaborating with the Nazis. But he spent just one night in prison, the Allies quickly realising he was just an innocent cartoonist.

Despite his controversial past, Hergé was always at pains to prevent his characters being used for political ends and, in later work, actively promoted multiculturalism.

In 1946, a publisher in Brussels, Raymond Leblanc, pitched Hergé the idea of a comics magazine built around Tintin. Leblanc was a decorated resistance hero and his willingness to work with the then still ostracised Hergé helped to rehabilitate the author’s reputation.

Tintin magazine offered plenty of room for other artists, too, including Edgar Pierre Jacobs (Blake and Mortimer), Paul Cuvelier and Jacques Laudy. It set a new standard for European comics and championed the ligne claire style.

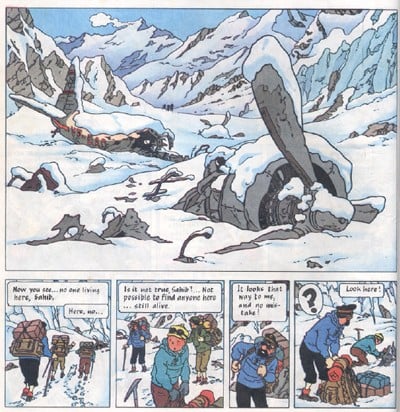

A few years later in 1950, the artist launched Studio Hergé, which assembled a team of assistants, cartoonists and colourists to help him in the creative process. Despite his enormous success, Hergé’s personal life in the post-war period was tumultuous, punctuated by marital crises and nervous breakdowns that brought him recurring nightmares. It was in this context that he created Tintin in Tibet (1958-1959) as a sort of therapy. This story, a masterpiece of minimalism and emotional exploration without traditional “baddies”, helped the artist to work through his problems.

Tintin in Tibet may have been Hergé’s artistic high water mark, but it also brought him writer’s block. New Tintin stories came less frequently, but continued in a more experimental direction. In The Castafiore Emerald (1961), for example, there are none of the customary globetrotting adventures: instead, all the action takes place at Marlinspike Hall.

In the last Tintin comics, there are noticeable changes in the way characters dress and act. In Tintin and the Picaros (1975-1976), for instance, we see Tintin wearing jeans and doing yoga, something that did not go down well with all readers.

Hergé’s legacy

Hergé had a profound impact on the history of comics. The Tintin comics were international bestsellers, thrilling fans of all ages around the world.

Key to their success were stories rooted in reality and a mix of humour, tragedy and suspense. Hergé passed away in 1983 at the age of 75, bringing the Tintin series to an end. He was survived by his widow, Fanny Rémi, who set up a foundation to protect his legacy.

Despite the controversies, Hergé’s influence and legacy is undeniable. And it’s backed up by numerous international accolades, from the use of Tintin to promote tourism in Belgium to the streets named after him: he was and remains one of the most influential European comics artist in the world.