Table of Contents

There are two problems with the way that rhetorical devices are usually covered in the classroom:

- We’re taught how to recognise rather than use them.

- We’re often given the impression that they’re literary devices employed principally in written texts.

This article is a mini guide on how to use some of the most common rhetorical devices for creating creative and effective marketing content. In other words, we’ll be looking at rhetorical devices as a practical way for meeting marketing briefs.

Metaphor. Solving the problem by asking what something is like

“Get me out of here, out of this problem, take me to a place where it has already been solved”. That’s the prayer that a creative is saying when they turn to a metaphor to, say, create an ad page. It’s a request in keeping with the etymological meaning of this word, which is derived from the Greek “metapherein”, meaning “to transfer”. A metaphor is a change of semantic field. It works by implicitly asking us to imagine what the quality of a product or service is like. What it is like will take us somewhere else, where the quality of that product or service has already been demonstrated. Let’s look at an example.

Problem: conveying the quality of a beer

Let’s imagine that you have to communicate the quality of a premium beer. It’s not just about the ingredients or the way it’s brewed. You have to create a greater perception of quality, one that’s more abstract and less connected to individual features of the product.

Solution: metaphor

How do you visualise such an abstract sense of quality and luxury? Metaphor is the perfect device: it makes visible and tangible characteristics that are too abstract to be represented directly. The way we have to think is simple: we have to ask ourselves what the product is “like”? What the product is like will be the vehicle that takes us into semantic fields where quality and value are easily representable and understandable for the public.

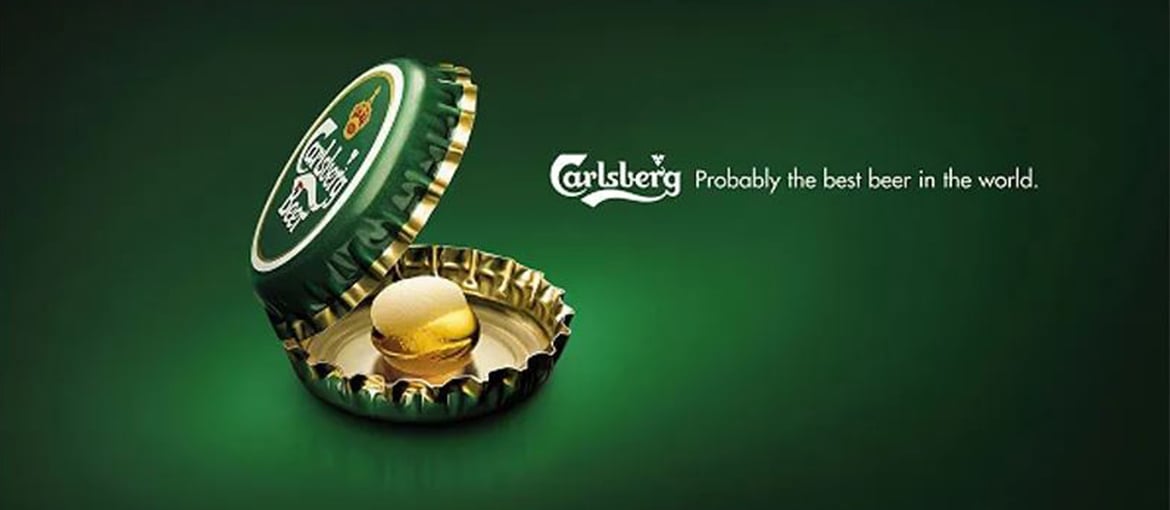

This beer is precious like a… a jewel, a diamond or a pearl. Everyone knows that pearls are precious! And so we get: this beer is a pearl. Now all you have to do is show a drop of beer as if it were actually a pearl, perhaps between two bottle tops arranged to look like an open oyster shell.

Hyperbole. Solving problems with exaggeration

If the product or service really has superior quality, you can use hyperbole as a creative tool by asking yourself what the most extreme (and ironic or offbeat) consequences of this quality would be. Or, you can exaggerate people’s desire or need for a product. In either case, the question to ask yourself is: so much so that…?

Problem: conveying the quality of medicine

This time, we have to create a campaign to communicate the anti-inflammatory qualities of Voltarol, a well-known brand of medication used to treat joint and muscle pain.

Solution: hyperbole

Here we can use hyperbole in one of two ways. We can exaggerate the drug’s qualities, or we can exaggerate the need that we have for it when we have back pain. So, for example:

• This medication make you feel so good that… Extreme consequence > Nobody will ever need to stretch again and yoga teachers will go out of business.

• Back pain can make you feel so bad that… Extreme consequence > Even tying a shoe lace can seem impossible.

Often, the most memorable medicine adverts use a hyperbolic dramatisation of a health problem: it’s an approach that it more empathetic with and compelling to the public. And this Voltarol campaign is a case in point: simple everyday actions like tying a shoelace are shown using an exaggerated perspective that makes them seem like impossible tasks.

Litotes. Sometimes, to solve a problem, you need to beat about the bush

Litotes means understatement. It’s the opposite to hyperbole: instead of exaggerating a problem, you downplay it. It often consists in denying the contrary to what we should be communicating, when we’re worried that expressing ourselves too directly could turn the audience against us. Think about it: when teachers had to tell your parents that about your poor school performance, they didn’t say:

“He studies so little that he could get through school with just one pencil”. (Extreme consequence: hyperbole).

Rather, it was probably something like:

”Well, let’s just say that conscientious study is not exactly his strong point” (Denying the contrary: litotes).

Problem: conveying a bank’s quality

Bank Forum needed to communicate its credibility, based on discipline, order, precision and integrity. To solve this communication problem, it could have resorted to hyperbole: we’re so orderly that… and shown an extreme consequence. For example, meticulously tidy desks, with every item organised by shape and colour. But this approach can be tricky: it could have given the impression of a self-congratulatory brand talking about itself. It might have put off the public. And this is where litotes can help.

Solution: litotes

Instead of showing an extreme consequence of the concept of order, litotes would have us deny its contrary. So, instead of showing that “we’re neat and tidy to a fault”, we can show that “disorder isn’t exactly in our style”. How can we do this? With this great ad that shows a particularly neatly turned out bank employee with a tiny bit of hair out of place. As the headline tells us, this is the most disorder that a German bank can imagine.

Metonymy (and synecdoche). Solving a problem by changing the terms

Metonymy and synecdoche are methods based on swapping one concept for another that’s related to it.

• In metonymy, the swap is qualitative.

For example, the contents for the container. When someone says “I drank the whole can“, we obviously understand that they mean the contents of the can and not the can itself.

• In synecdoche, the relationship is quantitative.

For example, the whole for a part. “Italy won the Euros” to say that “the Italian national football team won the Euros”

Problem: conveying the quality of a washing detergent

This time, the problem consists in communicating the quality of a washing detergent. You’ve been asked to emphasise its effectiveness in eliminating bad odours from dirty laundry.

Solution: metonymy

The rhetorical device metonymy leads us to, for example, switch cause for effect. So, you might wonder: “What’s making my clothes smell bad?” The answer might be the fast-food joints you’ve been hanging out in. A burger can most certainly leave your shirt smelling unpleasant. But if the burger is the cause of the smell, you can instead represent it as the effect. That’s how you get to the visual of a pile of clothes arranged to look like a burger. The result becomes visually interesting because it links the beginning and the end of a whole story.

Personification. If your problem were a person, who would it be?

Personifying a product or service means giving it human characteristics: a personality, a voice, strengths, weaknesses. As a person, your product will be able to perform a range of actions that are easy for the audience to decipher. Because of its simplicity, personification is often used in the toy or mass market sectors: muscular cleaning products that scrub your stove for you; sweets that embark on thrilling adventures; and so on and so forth. The downside? Personification is a somewhat dated method for resolving communication problems and very often smacks of déjà-vu. This means that the element of surprise and relevance is much diminished. Fortunately, we have an ace up our sleeve. Let’s see what it is.

Problem: conveying the quality of a glue

In the world of household glues, Loctite is well known for its strength and speed. After years of ads emphasising its technical characteristics, the time has come for warmer, more emotional campaign. But is that possible?

Solution: personification

Personifying the product, making it walk and talk, risks creating something tacky and childish that’s doesn’t fit the brand’s tone of voice. But, as we said before, there’s an ace up our sleeve: a clever approach is not to personify the product directly, but instead something connected to it. For example, an old ornament or broken toy with particular sentimental value. In this ad, the soldier is personified and scaled up to human size so that it can hug the person who mended him. Here, personification emphasises real emotions: we’ve all got an old toy or object we’re especially fond of and attached to, almost as if an actual friend. Fixing one of these is a bit like being able to hug it again.

Metaphor, hyperbole, litotes, metonymy, synecdoche and personification. In this article, we’ve learnt how to use these rhetorical devices to create effective marketing content. Why not try using these in your next project?